I am re-posting on Tacrolimus drops and ointment for use in patients with Dry Eye symptoms.

We have used Tacrolimus in about 8 patients with variable success. It has not been a “wow” for most patients but has helped for the majority to some extent. It can be prescribed as a drop or ointment depending on the compounding pharmacy’s experience.

It is Rx 0.03% 1 drop bid or ointment in most studies. (**)

Tacrolimus is often prescribed for T cell-mediated diseases such as:

1. eczema or atopic dermatitis

2. psoriasis

3. Vitiligo

Orally Tacrolimus is used to:

1. prevent organ rejection

2. Uveitis after Bone Marrow transplantation

3. Minimal change disease of the kidney

4. Kimura’s disease

Clinical treatment of dry eye using 0.03% tacrolimus eye drops.

Author information

- 1

- Department of Ophthalmology, School of Medicine, University of São Paulo (Hospital das Clínicas of da Universidade de São Paulo), São Paulo, Brazil.

Abstract

PURPOSE:

METHODS:

RESULTS:

CONCLUSIONS:

I wanted to add all the risks of Tacrolimus (Protopic) in the literature for patients who have been prescribed this by their dermatologist.

Wilkipedia has a good review below as well: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tacrolimus

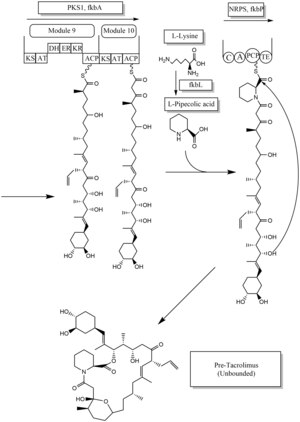

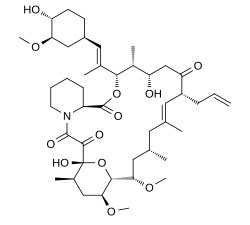

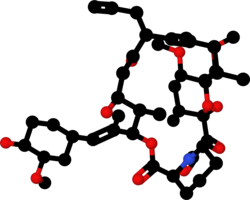

Tacrolimus (i.e., fujimycin or FK-506): Chemically tacrolimus is a 23-membered macrolide lacton macrolide (similary to many known antibiotics) that was first discovered in 1987 from the fermentation broth of a Japanese soil sample that contained the bacterium Streptomyces tsukubaensis. It is an immunosuppressant used for liver transplant rejection prophylaxis and is under investigation for use in kidney, cardiac, pancreas, small bowel, and bone marrow transplantation. It is also used in a variety of autoimmune disease. Its mechanism of action is similar to that of cyclosporine, but with 10- to 100-fold greater potency.

In ophthalmology, topical tacrolimus is used in immune-mediated conditions to decrease inflammation, such as:

-ocular allergy: especially atopic conjunctivitis and blepharitis

-graft-versus-host disease,

-corneal transplantation,

-ocular pemphigoid.

-ocular Sjögren’s syndrome (used as 0.03% ophthalmic solution)

-keratoconjunctivitis sicca (used as 0.03% ophthalmic solution)

The risks include below (from Wiki):

I could not find any paper saying Tacrolimus worsens meibomian gland dysfunction.

Side effects[edit]

By mouth or intravenous use[edit]

Carcinogenesis and mutagenesis[edit]

Topical use[edit]

Cancer risks[edit]

**

Topical 0.03% tacrolimus ointment in the management of ocular surface inflammation in chronic GVHD

Bone Marrow Transplantation 45, 957–958(2010)

We present a case in which topical tacrolimus 0.03% was used successfully in the management of ocular surface inflammation from chronic GVHD. Dry eye is the most common complication of chronic GVHD, occurring in 40–76% of patients.1 Inflammation of the ocular surface leads to aqueous deficiency and tear film instability; blindness could ensue from conjunctival cicatrization and corneal epithelial breakdown.2 The mainstay of treatment for ocular surface GHVD consists of lubrication and topical steroid,3 but the long-term use of the latter is limited by complications, such as cataract and glaucoma. Protopic (Tacrolimus 0.03%, Astellas Pharma, Tokyo, Japan) is a dermatological ointment approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for atopic eczema. Off-label ophthalmic use has emerged for eczematous eyelid disease, atopic keratoconjunctivitis and various other anterior segment inflammations with promising results.3, 4 Its twice-daily regimen, higher potency than commercially available calcineurin inhibitor (CYA 0.05%), lack of serious side effects and steroid sparing properties have made it ideal for at least short-term use when other modalities fail.

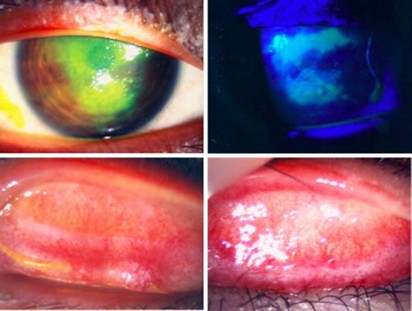

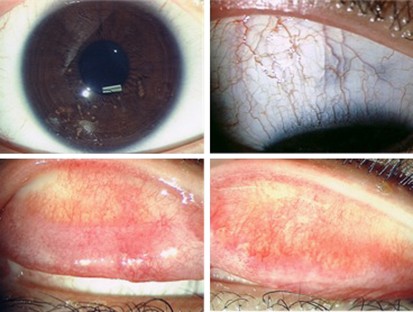

A 13-year-old Chinese boy was referred to the eye clinic in November 2008 with a 2-month history of bilateral intermittent redness and pain. He was a known case of Ph translocation-positive (Ph+) ALL diagnosed in July 2005. He was treated according to the ALL IC-BFM 2002 protocol. BM relapse in June 2007 prompted a PBSC transplant from his HLA-identical sister in November 2007. He then entered CR2. Review at 1 year showed complete donor chimerism and ongoing remission. Further PCR for BCR–ABL was negative. He developed chronic GVHD with pulmonary and gastrointestinal tract involvement, for which he was maintained with prednisolone 15 mg alternate daily and CYA 100 mg twice daily. His red eyes had been labeled before referral as infective conjunctivitis and treated with topical chloramphenicol without improvement. Initial corrected visual acuities were 20/40 for the right eye and 20/20 for the left eye. He was photophobic and actively tearing. Examination of the tarsal conjunctiva on eversion showed diffuse injection over the upper and lower lids bilaterally, with 50% fibrotic changes over the superior edges at each site. This was compatible with grade 3 ocular surface GVHD.5 He developed corneal epithelial breakdown despite 1 week of intensive topical steroid, preservative-free lubrication, bandage contact lens and lacrimal punctal occlusion (Figure 1). His vision dropped to 20/100. Clinically dry eyes were confirmed by negative Schirmer wetting (0 and 1 mm). It was suspected that a combination of dry eyes and mechanical damage from tarsal fibrosis had led to the corneal epithelial breakdown. The off-label use of dermatological tacrolimus 0.03% twice daily was discussed and commenced on the ninth week from symptom onset (1 week after corneal complication). He responded with complete corneal healing after 1 week and moderate reduction in conjunctivitis (Figure 2). Review by pediatricians a week after the start of topical tacrolimus prompted the escalation of systemic immune suppression. Oral prednisolone was increased from 15 mg to 30 mg alternate daily, CYA was maintained at 100 mg twice daily and mycophenolate mofetil 500 mg twice daily was added. Examination at 1 month showed normal vision of 20/20 bilaterally. He was not photophobic. Corneal epithelial defects healed completely and conjunctivitis resolved with asymptomatic fibrous scarring. Topical tacrolimus and prednisolone were both stopped; his eyes were stable at 5 months on preservative-free lubricants and systemic immune suppression.

Right eye, pre-treatment. Upper left: corneal epithelial breakdown under normal light, stained with fluorescein. Upper right: corneal epithelial breakdown, stained with fluorescein under cobalt blue light. Lower left: right upper tarsal surface, showing diffuse injection and subconjunctival cicatrization. Lower right: left upper tarsal surface, showing diffuse injection and subconjunctival cicatrization.

Right eye, at 1 month post-treatment. Upper left: normal cornea, no epithelial defect seen. Upper right: right superior bulbar conjunctiva, no sign of conjunctivitis. Lower left: right upper tarsal surface, Lower right: left upper tarsal surface, residual subconjunctival fibrotic tissue, minimal injection seen.

Reports on the efficacy of topical tacrolimus in ophthalmic diseases exist for both dermatological3 and specially prepared ophthalmic ointments.4 The most frequently reported side effect from the dermatological ointment was the blurring of vision caused by the viscous base, and a burning sensation, both of which were tolerated. Concerns are raised regarding the increased susceptibility to infection and skin malignancy as a result of local immunological suppression. The longest treatment duration for ocular use was 26 months in a 46-year-old man with peripheral ulcerative keratitis in whom no significant adverse effects were noted. Results from controlled long-term studies are, however, lacking.

Our case has illustrated the efficacy of topical tacrolimus in controlling ocular surface inflammation when conventional treatments have failed. Improvements were noticeable from the first week, a useful time period when decisions regarding the possible systemic immune suppression and its associated baseline evaluations are underway. The successful tapering of treatment after one month could be the effect of systemic immune suppression or the end to an exacerbated local inflammatory process. More data on the natural history of this condition are necessary to formulate the ideal treatment plan.

References

- 1

Ogawa Y, Kuwana M . Dry eye as a major complication associated with chronic graft-versus-host disease after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Cornea 2003; 22: S19–S27.

- 2

Mohammadpour M . Progressive corneal vascularization caused by graft-versus-host disease. Cornea 2007; 26: 225–226.

- 3

Young AL, Wong SM, Leung AT, Leung GYS, Cheng LL, Lam DSC . Successful treatment of surgically induced necrotizing scleritis with tacrolimus. Clin Experiment Ophthalmol 2005; 33: 98–99.

- 4

Miyazaki D, Tominaga T, Kakimaru-Hasegawa A, Nagata Y, Hasegawa J, Inoue Y . Therapeutic effects of tacrolimus ointment for refractory ocular surface inflammatory diseases. Ophthalmology 2008; 115: 988–992.

- 5

Robinson MR, Lee SS, Rubin BI, Wayne AS, Pavletic SZ, Bishop MR et al. Topical corticosteroid therapy for cicatricial conjunctivitis associated with chronic graft-versus-host disease. Bone Marrow Transplant 2004; 33: 1031–1035.

Eczema drugs tacrolimus (Protopic) and pimecrolimus (Elidel): cancer concerns

Tacrolimus Ointment for Refractory Posterior Blepharitis.

Abstract

PURPOSE:

METHODS:

RESULTS:

CONCLUSION:

Previous post:

Tacrolimus is often prescribed for T cell-mediated diseases such as:

1. eczema or atopic dermatitis

2. psoriasis

3. Vitiligo

Orally Tacrolimus is used to:

1. prevent organ rejection

2. Uveitis after Bone Marrow transplantation

3. Minimal change disease of the kidney

4. Kimura’s disease

Allergic contact dermatitis from tacrolimus.

Author information

- 1

- Department of Medicine, University of California, San Diego, California 92103-8420, USA. dwshaw@ucsd.edu

Abstract

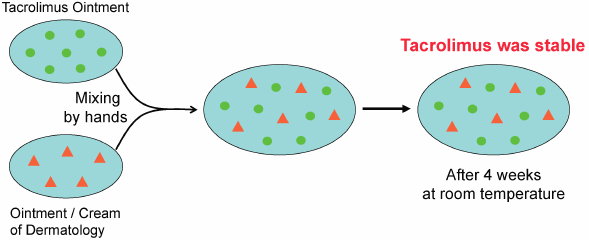

- 1) Eto T. Usage of topical steroids-propriety of mixed prescription. Jpn. J. Clin. Dermat., 55, 96–101 (2001).

- 2) Japanese Dermatological Association. Guideline of care for the management of atopic dermatitis 2016. Jpn. J. Dermatol., 126, 121–155 (2016).

- 3) Interview Form of protopic ointment 0.1%, Maruho Co., Ltd., 2017.

- 4) Ohtani M. Effect of the admixture of commercially available corticosteroid ointments and/or creams on their efficacy and side effects. Jpn. J. Pharm. Health Care Sci., 29, 1–10 (2003), and references cited therein.

- 5) Ohtani M, Yamaoka Y, Matsumoto M, Namiki M, Yamamura Y, Etoh T. Compatibility of adaparene gel (Differin® Gel) with other kinds of ointments or creams. Yakuzaigaku, 69, 470–476 (2009).

- 6) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tacrolimus#targetText=Tacrolimus%2C%20also%20known%20as%20fujimycin,the%20risk%20of%20organ%20rejection.

Tacrolimus

|

|

|

|

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Prograf, Advagraf, Protopic, others |

| Other names | FK-506, fujimycin |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| License data | |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration |

Topical, oral, iv |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 24% (5–67%), less after eating food rich in fat |

| Protein binding | ≥98.8% |

| Metabolism | Hepatic CYP3A4, CYP3A5 |

| Elimination half-life | 11.3 h for transplant patients (range 3.5–40.6 h) |

| Excretion | Mostly faecal |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.155.367 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C44H69NO12 |

| Molar mass | 804.018 g/mol g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

|

Medical uses[edit]

Organ transplantation[edit]

Ulcerative colitis[edit]

Skin[edit]

Lupus Nephritis

Contraindications and precautions[edit]

- Breast-feeding

- Hepatic disease

- Immunosuppression

- Infants

- Infection

- Neoplastic disease, such as:

- Oliguria

- Pregnancy

- QT interval prolongation

- Sunlight (UV) exposure

- Grapefruit juice[12]

Topical use[edit]

- Occlusive dressing

- Known or suspected malignant lesions

- Netherton’s syndrome or similar skin diseases

- Certain skin infections[8]

Side effects[edit]

By mouth or intravenous use[edit]

Carcinogenesis and mutagenesis[edit]

Topical use[edit]

Cancer risks[edit]

Interactions[edit]

Pharmacology[edit]

Mechanism of action[edit]

Pharmacokinetics[edit]

Pharmacogenetics[edit]

History[edit]

Available forms[edit]

Biosynthesis[edit]

See also[edit]

- Tohru Kino

- Stuart Schreiber

- Thomas Starzl

- FK1012, a derivative

- Ciclosporin

References[edit]

- ^ Berdoulay A, English RV, Nadelstein B (2005). “Effect of topical 0.02% tacrolimus aqueous suspension on tear production in dogs with keratoconjunctivitis sicca”. Veterinary Ophthalmology. 8 (4): 225–32. doi:10.1111/j.1463-5224.2005.00390.x. PMID 16008701.

- ^ “Tacrolimus for Dogs and Cats”.

- ^ a b McCauley, Jerry (2004-05-19). “Long-Term Graft Survival In Kidney Transplant Recipients”. Slide Set Series on Analyses of Immunosuppressive Therapies. Medscape. Retrieved 2006-06-06.

- ^ Haddad EM, McAlister VC, Renouf E, Malthaner R, Kjaer MS, Gluud LL (October 2006). McAlister V (ed.). “Cyclosporin versus tacrolimus for liver transplanted patients”. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 4 (4): CD005161. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005161.pub2. PMID 17054241.

- ^ O’Grady JG, Burroughs A, Hardy P, Elbourne D, Truesdale A (October 2002). “Tacrolimus versus microemulsified ciclosporin in liver transplantation: the TMC randomised controlled trial”. Lancet. 360 (9340): 1119–25. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11196-2. PMID 12387959.

- ^ Baumgart DC, Pintoffl JP, Sturm A, Wiedenmann B, Dignass AU (May 2006). “Tacrolimus is safe and effective in patients with severe steroid-refractory or steroid-dependent inflammatory bowel disease–a long-term follow-up”. The American Journal of Gastroenterology. 101 (5): 1048–56. doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00524.x. PMID 16573777.

- ^ Baumgart DC, Macdonald JK, Feagan B (July 2008). Baumgart DC (ed.). “Tacrolimus (FK506) for induction of remission in refractory ulcerative colitis”. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 16 (3): CD007216. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007216. PMID 18646177.

- ^ a b Haberfeld, H, ed. (2015). Austria-Codex (in German). Vienna: Österreichischer Apothekerverlag. Protopic.

- ^ Silverberg NB, Lin P, Travis L, Farley-Li J, Mancini AJ, Wagner AM, Chamlin SL, Paller AS (November 2004). “Tacrolimus ointment promotes repigmentation of vitiligo in children: a review of 57 cases”. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 51 (5): 760–6. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2004.05.036. PMID 15523355.

- ^ Singh JA, Hossain A, Kotb A, Wells G (September 2016). “Risk of serious infections with immunosuppressive drugs and glucocorticoids for lupus nephritis: a systematic review and network meta-analysis”. BMC Medicine. 14 (1): 137. doi:10.1186/s12916-016-0673-8. PMC 5022202. PMID 27623861.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Haberfeld, H, ed. (2015). Austria-Codex (in German). Vienna: Österreichischer Apothekerverlag. Prograf.

- ^ Fukatsu S, Fukudo M, Masuda S, Yano I, Katsura T, Ogura Y, Oike F, Takada Y, Inui K (April 2006). “Delayed effect of grapefruit juice on pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of tacrolimus in a living-donor liver transplant recipient”. Drug Metabolism and Pharmacokinetics. 21 (2): 122–5. doi:10.2133/dmpk.21.122. PMID 16702731.

- ^ Naesens M, Kuypers DR, Sarwal M (February 2009). “Calcineurin inhibitor nephrotoxicity” (PDF). Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 4 (2): 481–508. doi:10.2215/CJN.04800908. PMID 19218475.

- ^ Miwa Y, Isozaki T, Wakabayashi K, Odai T, Matsunawa M, Yajima N, Negishi M, Ide H, Kasama T, Adachi M, Hisayuki T, Takemura T (2008). “Tacrolimus-induced lung injury in a rheumatoid arthritis patient with interstitial pneumonitis”. Modern Rheumatology. 18 (2): 208–11. doi:10.1007/s10165-008-0034-3. PMID 18306979.

- ^ O’Donnell MM, Williams JP, Weinrieb R, Denysenko L (2007). “Catatonic mutism after liver transplant rapidly reversed with lorazepam”. General Hospital Psychiatry. 29 (3): 280–1. doi:10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2007.01.004. PMID 17484951.

- ^ Hanifin JM, Paller AS, Eichenfield L, Clark RA, Korman N, Weinstein G, Caro I, Jaracz E, Rico MJ (August 2005). “Efficacy and safety of tacrolimus ointment treatment for up to 4 years in patients with atopic dermatitis”. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 53 (2 Suppl 2): S186–94. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2005.04.062. PMID 16021174.

- ^ N H Cox & Catherine H Smith (December 2002). “Advice to dermatologists re topical tacrolimus” (PDF). Therapy Guidelines Committee. British Association of Dermatologists. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-12-13.

- ^ William F. Ganong (2005-03-08). Review of medical physiology(22nd ed.). Lange medical books. p. 530. ISBN 978-0-07-144040-0.

- ^ Liu J, Farmer JD, Lane WS, Friedman J, Weissman I, Schreiber SL (August 1991). “Calcineurin is a common target of cyclophilin-cyclosporin A and FKBP-FK506 complexes”. Cell. 66 (4): 807–15. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(91)90124-H. PMID 1715244.

- ^ Abou-Jaoude MM, Najm R, Shaheen J, Nawfal N, Abboud S, Alhabash M, Darwish M, Mulhem A, Ojjeh A, Almawi WY (September 2005). “Tacrolimus (FK506) versus cyclosporine microemulsion (neoral) as maintenance immunosuppression therapy in kidney transplant recipients”. Transplantation Proceedings. 37 (7): 3025–8. doi:10.1016/j.transproceed.2005.08.040. PMID 16213293.

- ^ a b Dinnendahl, V; Fricke, U, eds. (2003). Arzneistoff-Profile (in German). 9 (18 ed.). Eschborn, Germany: Govi Pharmazeutischer Verlag. ISBN 978-3-7741-9846-3.

- ^ Bains, Ripudaman Kaur. “Molecular diversity and population structure at the CYP3A5 gene in Africa” (PDF). University College London. Retrieved 13 June 2016.

- ^ Staatz CE, Tett SE (2004). “Clinical pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of tacrolimus in solid organ transplantation”. Clinical Pharmacokinetics. 43 (10): 623–53. doi:10.2165/00003088-200443100-00001. PMID 15244495.

- ^ Staatz CE, Goodman LK, Tett SE (March 2010). “Effect of CYP3A and ABCB1 single nucleotide polymorphisms on the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of calcineurin inhibitors: Part I”. Clinical Pharmacokinetics. 49 (3): 141–75. doi:10.2165/11317350-000000000-00000. PMID 20170205.

- ^ Staatz CE, Goodman LK, Tett SE (April 2010). “Effect of CYP3A and ABCB1 single nucleotide polymorphisms on the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of calcineurin inhibitors: Part II”. Clinical Pharmacokinetics. 49 (4): 207–21. doi:10.2165/11317550-000000000-00000. PMID 20214406.

- ^ Barbarino JM, Staatz CE, Venkataramanan R, Klein TE, Altman RB (October 2013). “PharmGKB summary: cyclosporine and tacrolimus pathways”. Pharmacogenetics and Genomics. 23(10): 563–85. doi:10.1097/fpc.0b013e328364db84. PMC 4119065. PMID 23922006.

- ^ Benkali K, Prémaud A, Picard N, Rérolle JP, Toupance O, Hoizey G, Turcant A, Villemain F, Le Meur Y, Marquet P, Rousseau A (2009-01-01). “Tacrolimus population pharmacokinetic-pharmacogenetic analysis and Bayesian estimation in renal transplant recipients”. Clinical Pharmacokinetics. 48 (12): 805–16. doi:10.2165/11318080-000000000-00000. PMID 19902988.

- ^ Choi Y, Jiang F, An H, Park HJ, Choi JH, Lee H (January 2017). “A pharmacogenomic study on the pharmacokinetics of tacrolimus in healthy subjects using the DMETTM Plus platform”. The Pharmacogenomics Journal. 17 (1): 105–106. doi:10.1038/tpj.2016.85. PMID 27958377.

- ^ Hatanaka H, Iwami M, Kino T, Goto T, Okuhara M (November 1988). “FR-900520 and FR-900523, novel immunosuppressants isolated from a Streptomyces. I. Taxonomy of the producing strain”. The Journal of Antibiotics. 41 (11): 1586–91. doi:10.7164/antibiotics.41.1586. PMID 3198493.

- ^ Kino T, Hatanaka H, Hashimoto M, Nishiyama M, Goto T, Okuhara M, Kohsaka M, Aoki H, Imanaka H (September 1987). “FK-506, a novel immunosuppressant isolated from a Streptomyces. I. Fermentation, isolation, and physico-chemical and biological characteristics”. The Journal of Antibiotics. 40 (9): 1249–55. doi:10.7164/antibiotics.40.1249. PMID 2445721.

- ^ Pritchard DI (May 2005). “Sourcing a chemical succession for cyclosporin from parasites and human pathogens”. Drug Discovery Today. 10 (10): 688–91. doi:10.1016/S1359-6446(05)03395-7. PMID 15896681. Supports source organism, but not team information

- ^ Ponner, B, Cvach, B (Fujisawa Pharmaceutical Co.): Protopic Update 2005

- ^ a b c Joint Formulary Committee. “British National Formulary (online)”. London: BMJ Group and Pharmaceutical Press. Retrieved 24 September 2015.

- ^ a b c Ordóñez-Robles M, Santos-Beneit F, Martín JF (May 2018). “omic Approaches”. Antibiotics. 7 (2): 39. doi:10.3390/antibiotics7020039. PMC 6022917. PMID 29724001.

- ^ Chen D, Zhang L, Pang B, Chen J, Xu Z, Abe I, Liu W (May 2013). “FK506 maturation involves a cytochrome p450 protein-catalyzed four-electron C-9 oxidation in parallel with a C-31 O-methylation”. Journal of Bacteriology. 195 (9): 1931–9. doi:10.1128/JB.00033-13. PMC 3624582. PMID 23435975.

- ^ Mo S, Ban YH, Park JW, Yoo YJ, Yoon YJ (December 2009). “Enhanced FK506 production in Streptomyces clavuligerus CKD1119 by engineering the supply of methylmalonyl-CoA precursor”. Journal of Industrial Microbiology & Biotechnology. 36(12): 1473–82. doi:10.1007/s10295-009-0635-7. PMID 19756799.

External links