FOOD: How to choose best food to heal your symptoms?

Years ago, it seemed as if no one ever talked about “going Gluten Free,” or “a low inflammatory diet,” or “going Carb Free.”

What is all this craze about?

Mostly, the issue is that traditional medicine does not have all the answers and more research is showing the power of natural foods to heal many patients’ ailments.

Choosing the right foods to heal yourself of a symptoms does not have to be hard.

Following the below simple rules, may help determine the underlying cause of your symptoms or condition, help heal you naturally, and help you and your doctors determine if you DO need traditional medicines which do work for most conditions. Contrary to popular relieve, most MDs, like myself, do prefer to treat patients naturally before trying prescription medicines or surgery.

Genetics plays a big part in one’s health and thus what you choose to eat should be guided by your family and genetic history. For instance, if you have a strong family history of Diabetes, avoid excessive carbohydrates as early in age as possible. If you have a strong family history of prostate cancer, eat plenty of organic tomatoes for the lycopene.

If you are having difficulty recovering from a virus or head cold, focus on increasing your anti-oxidant intake, Vitamin D production, Vitamin C intake ideally naturally & get plenty of fluids and rest: this will help your immune system fight the virus.

If you have chronic headaches and migraines, see my Migraine Diet Sheet to see the best plan of attack (in general): https://drcremers.com/2014/02/migraine-diet-recommended-and-not.html

This

is an area that most MDs are very skeptical about and for good reason:

there have not been great randomized, double blinded controlled studies

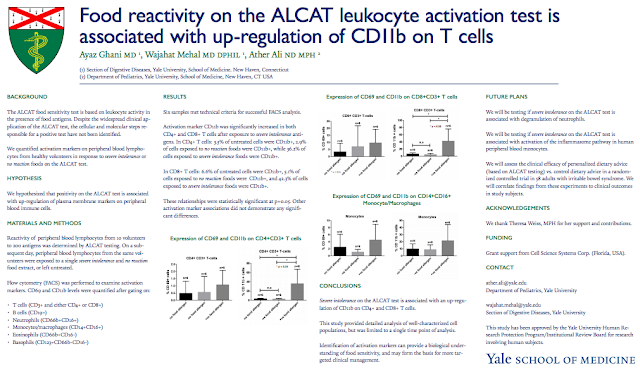

that prove that nature-based diets (such as ALCAT below) works.

However, there has been more research on these tests and diets as noted

below and through links below.

It does make sense: use

certain organic foods to heal yourself. Avoid “dangerous foods.” Try to

rarely eat “potentially dangerous food” based on one’s genetic profile.

Recently

2 MDs friends, one from medical school at Brown, told me of their

journey to be cured of two debilitating disease. Both tried the medical

route: with many prescriptions and side effects.

Finally, after

given up on traditional medicine, they researched alternatives and found

hope if not a total cure in the site below and in natural remedies. One

is still struggling with his diagnosis but feels much better.

I

include the information for patients who want to know more. I have

written about my own unusual diet: currently mostly seaweed, pecans,

almonds, almond milk, Stevia water, and plenty of fresh veggies, salad,

and wild salmon; almost no wheat, rice, and very limited meat: at most

3x/month; eggs about 1-2 per week; cheese & cottage cheese on

occasion; rarely beans (has a lot of fiber but also a lot of carbs). I

do not recommend this diet unless one has a strong family history of

diabetes. But I must note that a few months ago, I started noting a pain

in my left, 2nd finger’s joint (PIP), which for any surgeon is a

concern, soon after the diet change, the pain went away completely. Was

it the humidity, weather, loosing some weight or just the diet change? I

might never know. But my study of 1 was interesting enough to look in

to the below theories.

The next step is for someone to

donate funds to study such theories and diets objectively, without drug

company money. Time will tell if these natural remedies are worth the

out-of-pocket expense they sometime entail.

For now, many MD friends are beginning to look into this to treat themselves and their friends.

I am researching this more to find out what other studies have been done on this particular theory.

Sandra Lora Cremers, MD, FACS

Below

are the sites a close friend from medical school, who was at the top of

her class, used for healing. I am hesitant to endorse these as I have

not used them or been evaluated by ALCAT. However, my friend’s testimony

was so strong, it seems all patients should at least know about these

alternative testing and treatment options especially since few medical

schools discuss these things with med students.

1. https://www.alcat.com/pages/clinical_info/

2.

ALCAT | Available for over 25 years

Alcat Test is a lab based immune stimulation test in which a patient’s

WBC’s are challenged with various substances including foods, additives,

colorings, chemicals, medicinal herbs, functional foods, molds and

pharmaceutical compounds. The patient’s unique set of responses help to

identify substances that may trigger potentially harmful immune system

reactions.

Danuta Mylek studied 72 patients who followed an ALCAT based

elimination diet; they had significant improvement in their symptoms

that included arthritis, bronchitis and gastro issues. Specifically,

they found improvement in 83% of arthritis patients, 75% of Urticaria,

bronchitis, and gastroenteritis patients, 70% of migraine patients, 60% of chronic fatigue syndrome patients,

50% of asthma patients, 49% of AD patients, 47% of rhinitis patients

and 32% of hyperactivity patients. Patients were also skin tested for

IgE allergy to inhalants and foods that were more pronounced in skin and

nasal symptoms. Published in Advances in Medical Sciences; Formerly

Roczniki Akademii Medycznej w Białymstoku Volume 40, Number 3, 1995.

The ALCAT Test – A Guide and Barometer in the Therapy of Environmental and Food Sensitivities

Barbara A. Solomon MD studied 172 patients successfully using an ALCAT

Test-based diet to alleviate the following range of symptoms: classic

migraine (85%), common migraine (62%), sinus headaches (58%),

gastoesphageal reflux (GERD) (75%), IBS (71%), inflammatory arthritis

(65%), recurrent Sinusitis (59%), tension fatigue syndrome (60%), obesity

(50%), eczema (55%), asthma (30%), depression and/or anxiety (31%),

recurrent vaginitis (20%), recurrent urinary tract infection (46%),

degenerative arthritis (44%) and allergic rhinitis (42%). Published in

Environmental Medicine, Volume 9, Number 1 & 2, 1992. Barbara

Solomon MD, MA

Migraine/Headache

Inmunologic de Catalunya. Informe final de resultados estadisticos.

version 3, 28 de diciembre de 2006. (translated English version HERE )

is a study of 21 patients (2 men and 19 women) with migraines and with

positive results on the ALCAT test for at least one evaluated food and

have been included with the objective of comparing the number of

migraines reported during a period of diet of 3 months (phase I) and

another period of 3 months without any dietary restriction (phase II).

The hypothesis of this study began by considering that patients with

migraines have intolerance to certain food, determined by the ALCAT

test. Also, the foods the ALCAT tested as positive aggravated

migraines. Therefore, a diet that avoids these foods would improve

migraines, in the number of monthly attacks, intensity of pain and

duration of the attacks. Study by Immunological Center of Catalunya, IMS

Health: Health Economics and Outcomes Research—Influence of Food

Intolerance in Migraines: Final Report of Statistical Results. Version

3, December 28, 2006.

half of the patients included (47.6%) reduced the number of migraine

attacks per month between the inclusion phase in the study and the phase

of dietary restriction.The percentage of patients that suffered attacks

for more than 12 hours decreased from 57.1% in the inclusion phase to

47.6% in the dietary restriction phase.The frequency of appearance of

accompanying symptoms such as photophobia and phonophobia between the

inclusion phase and the dietary restriction phase was reduced from 47.7%

to 28.4% in the first case and from 35.7% to 23.3% in the second.

Pilot Study Into The Effect of Naturally Occurring Pharmacoactive Agents on the ALCAT Test.

PJ Fell used the ALCAT test to successfully determine cellular

reactions to Pharmacoative agents found in foods that trigger migraine

headaches. Presented at Annual Meeting of the American Otolaryngic

Allergy Association, September 27, 1991; Kansas City, MO. P.J. Fell, MD

ALCAT Test Results In The Treatment of Respiratory and Gastrointestinal Symptoms, Arthritis, Skin and Central Nervous System

Danuta Mylek studied 72 patients who followed an ALCAT based

elimination diet; they had significant improvement in their symptoms

that included arthritis, bronchitis and gastro issues. Specifically,

they found improvement in 83% of arthritis patients, 75% of Urticaria,

bronchitis, and gastroenteritis patients, 70% of migraine patients, 60%

of chronic fatigue syndrome patients, 50% of asthma patients, 49% of AD

patients, 47% of rhinitis patients and 32% of hyperactivity patients.

Patients were also skin tested for IgE allergy to inhalants and foods

that were more pronounced in skin and nasal symptoms. Published in

Advances in Medical Sciences; Formerly Roczniki Akademii Medycznej w

Białymstoku Volume 40, Number 3, 1995.

The ALCAT Test – A Guide and Barometer in the Therapy of Environmental and Food Sensitivities

–Barbara A. Solomon MD studied 172 patients successfully using an ALCAT

Test-based diet to alleviate the following range of symptoms: classic

migraine (85%), common migraine (62%), sinus headaches (58%),

gastoesphageal reflux (GERD) (75%), IBS (71%), inflammatory arthritis

(65%), recurrent Sinusitis (59%), tension fatigue, syndrome (60%),

obesity (50%), eczema (55%), asthma (30%), depression and/or anxiety

(31%), recurrent vaginitis (20%), recurrent urinary tract infection

(46%), degenerative arthritis (44%) and allergic rhinitis (42%).

Published in Environmental Medicine, Volume 9, Number 1 & 2, 1992.

Barbara Solomon MD, MA

PJ Fell PJ, J Brostoff, and MJ Pasula demonstrated in a study of 19

patients an overall correlation between ALCAT and DBC at 83.4%,

suggesting that the ALCAT Test was quite reliable in identifying unsafe

foods in these sensitive subjects. Presented at 45th Annual Congress of

the American College of Allergy and Immunology, Los Angeles, CA:

November 12-16, 1988 Peter I. Fell, MD, Director; Oxford Allergy Centre,

London Jonathon Brostoff, MA DM USc FRCP FRCPath, Dept. of Immunology,

University College & Middlesex School of Medicine, London Mark I.

Pasula, Ph.D., Research Director; AMTL Corp., Miami, F

MORE

THAN ANY other league in American sports, the NBA is an aspirational

technocracy. Adam Silver, its flowchart-savvy new commissioner, travels

the country championing analytics and innovation. The D-League functions

not only as the game’s minor leagues but also, per the NBA’s official

phraseology, as its “research and development laboratory.” And thanks to

the August sale of the Clippers to former Microsoft CEO Steve Ballmer,

about 1 in 3 majority owners in the NBA can now trace their billions to

the tech industry.

So

maybe it shouldn’t be surprising that Silicon Valley is transforming

how teams scrutinize, optimize and fundamentally think about their

players — or that Dr. Leslie Saxon, executive director of the Center

for Body Computing at the University of Southern California, contends

that the NBA is leading society into the biometric revolution. “We’ve

been inundated with all these companies coming up with different things

to look at and test,” says Gregg Farnam, longtime Timberwolves trainer

and the chairman of the National Basketball Athletic Trainers

Association. “It’s the explosion of data and data collection.”

But

what might come as a surprise is how significant that explosion has

been, and how far its blast radius might soon reach. The literary

specter haunting sports’ burgeoning Information Age is no longer Michael

Lewis and Moneyball but George Orwell and 1984.

The

boom officially began during work hours. Before last season, all 30

arenas installed sets of six military-grade cameras, built by a firm

called SportVU, to record the x- and y-coordinates of every person on

the court at a rate of 25 times a second — a technology originally

developed for missile defense in Israel. This past spring, SportVU

partnered with Catapult, an Australian company that produces wearable

GPS trackers that can gauge fatigue levels during physical activity.

Catapult counts a baker’s dozen of NBA clients, including the

exhaustion-conscious Spurs, and claims Mavericks owner Mark Cuban as

both a customer and investor. To front offices, the upside of such

devices is rather obvious: Players, like Formula One cars, are luxury

machines that perform best if vigilantly monitored, regulated and

rested.

But

to follow this logic to its conclusion is to understand why the scope

of this monitoring is expanding, and faster than the public knows. Teams

have always intuited that on-court productivity could be undermined by

off-court choices — how a player exhausts himself after hours, for

instance, or what he eats and drinks. Now the race is on to

comprehensively surveil and quantify that behavior. NBA executives have

discovered how to leverage new, ever-shrinking technologies to supervise

a player’s sleeping habits, record his physical movements, appraise his

diet and test his blood. In automotive terms, the league is investing

in a more accurate odometer.

“We

need to be able to have impact on these players in their private time,”

says Kings general manager Pete D’Alessandro. “It doesn’t have to be us

vs. you. It can be a partnership.”

A

lovely sentiment, at least in theory. But how long will it be until

biometric details impact contract negotiations? How long until graphs of

off-court behavior are leaked to other teams or the press? How long

until employment hinges on embracing technology that some find invasive?

“Employers

dictating the health care of their employees is a conflict of interest

that cannot be overcome,” says Alan C. Milstein, a leading bioethics

attorney and sports litigator who often represents NBA players. “I just

refuse to believe that the purpose of monitoring on any long-term basis

is the health of the employee. If the purpose is to predict performance,

that’s not a health care purpose. That’s an economic purpose.”

No

complaints have been filed to the National Basketball Players

Association as of yet. But it is worth noting that these partnerships

have developed so quietly that the union had not even developed a

position on the concept until ESPN requested comment in August. “If the

league and teams want to discuss potentially invasive testing procedures

that relate to performance, they’re free to start that dialogue and

we’ll be glad to weigh the benefits against the risks,” says longtime

NBPA counsel Ron Klempner, who served as interim executive director from

February 2013 to September 2014. “Obviously, we’d have serious privacy

and other fairness concerns on behalf of the players. We’ve barely left

the starting line on these issues.”

In the meantime, locked doors have swung open already.

ANDRE

IGUODALA’S TV used to cackle into the early morning, the laugh track of

The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air echoing in the semidarkness of his master

bedroom. For years, this was the All-Star swingman’s post-midnight

routine: watch reruns around 2 a.m.; pass out around 4; wake up around

8; drag self to gym; repeat. Iguodala traces the insomnia back to the

University of Arizona, where he’d toss and turn over his pro future. But

it was only last season, with his 30th birthday staring him in the

face, that the newly hired Warrior surrendered his problem to an

employer. “I told them that I needed to see a sleep therapist ASAP,”

Iguodala says. “And it’s funny: Keke told me he’d been thinking about

the same thing.”

Keke

Lyles, Golden State’s director of athletic performance, had already

been researching what amounts to an open secret about NBA slumber:

Players sleep as lightly as undergrads during finals week but nap harder

than Spanish plutocrats. Iguodala’s typical game-day siestas, for

example, ran three to four hours. “Even if they’ve been out all night,”

says Grizzlies trainer Drew Graham, “most of them take naps and think

that’s enough. They see the other guys do it.”

The problem with that strategy, however, is quantifiable.

A Stanford School of Medicine study of 11 men’s basketball players,

published in the journal Sleep in 2011, found that getting 10 hours a

night not only reduced fatigue and injury risk but also improved

accuracy at the foul line (by 9 percent) and behind the arc (9.2

percent). More recently, at the Sloan Sports Analytics Conference in

March, front office execs heard a Harvard Medical School professor

declare that a 25-year-old who sleeps four hours a night for one week

possesses the degraded testosterone levels of someone who’s 36. “If you

told an athlete you had a treatment that would reduce the chemicals

associated with stress, that would naturally increase human growth

hormone, that enhances recovery rate, that improves performance, they

would all do it,” says Mavericks trainer Casey Smith. “Sleep does all of

those things.”

So

it was last season that Iguodala became one of several Warriors to wear

the UP by Jawbone, a wristband weighing less than an ounce and covered

in rubber that monitors sleep habits by tracking the arm’s slightest

movements. (Before the availability of such devices — and the ensuing

graphs illustrating quantity and quality of sleep — teams could only

gather data from questionnaires. “And one thing we’ve found out,” Lyles

says, “is that guys who used to say that they got nine hours of sleep

every night actually got more like five.”) Iguodala also agreed to a

no-screens-in-bed policy under Lyles and now bans his beloved TV from

his bedroom. He stores his cellphone in the bathroom overnight. He keeps

the temperature at precisely 57 degrees, to lower his body’s core

temperature. His game-day naps have been cut down to an hour. His new

in-season routine, which begins at 11:15 p.m., proceeds as follows:

stretch; do breathing exercises; read a book for 15 to 20 minutes;

lights out by midnight; repeat.

“Once

guys get a feeling for performing at a higher level,” says Jeremy

Holsopple, the Mavericks’ athletic-performance director, “it’s a big

difference from feeling like s—. Which they didn’t even think was

feeling like s—.”

Dallas

managed its own sleep program last season, inspecting rest in two-week

blocks with a motion-detecting watch called a Readiband. Five franchises

— three of them playoff teams — also convinced players to wear a

skin-adhesive, torso-mounted sensor that is colloquially known within

front offices as “the patch.” The device tracks sleep habits but also

skin temperature, body position and heart-rate variability (which is

linked to stress). As a result, the patch can discern when a player

pulls on the covers at night, when he lies down, when his pulse races

and — on account of alcohol’s observable effect on heartbeat — when he

passes out drunk.

If

it sounds like the technocratic normalizing of surveillance, it is.

“It’s part of a growing trend of employers trying to take a peek into

personal lives,” says Dr. Arthur L. Caplan, the director of New York

University’s medical ethics division and the co-director of its Sports

and Society Program. “But there are slippery-slope risks. Goals can

easily slide from improving performance to preventing you from putting

yourself at risk to making sure you don’t do anything to embarrass the

team. I’d be very, very cautious.”

Yes,

Iguodala, a star veteran with a $48 million contract, may now feel

confident experimenting with sleep under the guidance of the Warriors.

But what happens later, as the program becomes more established and a

scrub is presented with the choice to volunteer? “‘Voluntary’ is a must,

and I’m sure some teams mean it,” Caplan says. “But there’s still a

huge difference in job security between a superstar and a marginal

player. If you’re the 12th guy on an NBA bench, you probably don’t feel

quite as free to say no.”

JEREMY

HOLSOPPLE IS standing on the third floor of Chicago’s Palmer House

Hilton on a bright May afternoon. The National Basketball Strength and

Conditioning Association’s annual vendor show is in full swing, and all

around him, 39 companies flash terms like “astronaut-tested,”

“body-scanning” and “cell systems.” At one table, Alex McKechnie, the

Raptors’ assistant coach and director of sports science, grouses about

user interface with an inventor of heart monitors. At another, Bryan

Doo, the Celtics’ strength-and-conditioning coach, inquires about a

headset that interprets electrochemical brain activity. But what most

intrigues Holsopple, entering his second season in Dallas, is relatively

simple.

“Fatigue

and load are the biggest things we’re looking at right now,” he says.

“I think you can honestly say that teams lose 10 to 15 games a year

because players aren’t even remotely close to physical and mental

freshness.”

If

SportVU cameras and GPS trackers have proved anything about on-court

behavior, it is that basketball time is hardly created equal. A minute

of Thunder guard Russell Westbrook, who starts and stops like a

Lamborghini in the open floor, is nothing like a minute of center

Kendrick Perkins, a moving van who all but beeps while backing into the

paint. The true load exacted on a player’s body is a physics equation

that varies based on mass, distance, speed and acceleration. And it

applies whenever they are doing anything, anywhere; a power forward who

takes boxing lessons after work unmistakably adds to the cumulative

fatigue on his body. “Practice is only part of a 24-hour day,” says

Lyles. “Solely using that as our gauge for how much or how little we

should be doing with guys probably isn’t a very good way to do it.”

Enter

the patch, made by Proteus Digital Health. Far more than just a sleep

monitor, the patch also boasts the capacity to continuously collect

accelerometer data — and wirelessly transmit it onto a team-owned phone

or computer. Weighing 9.5 grams, the gray 4-inch oval can be stuck to

the skin and forgotten about in the process. Todd Thompson, Proteus’ VP

of corporate development, contends that without the patch’s access to

and analysis of off-court player movements, any coaching staff that

adjusts practice intensities and travel schedules does so on perilously

incomplete information.

Imagine

an NBA season as a horizontal graph of the load on a player’s body,

dotted with strategically chosen peaks (for games of the utmost

importance) and valleys (where rest is necessary to cut down the odds of

injury). Imagine the capacity to generate an all-encompassing version

of that graph, down to the hour a player tired himself out chasing his

kids in his backyard — or doing something significantly less

family-friendly. Imagine a sortable chart that lists, for each rung of

the depth chart, a color-coded number representing current overall

fatigue level. The market for that kind of risk-management solution is

self-evident.

“General

managers, owners, presidents, they’re all looking at how much money

they’re losing due to sports injuries,” says Suns trainer Aaron Nelson.

According to a recent study by Rotowire, the average NBA team

hemorrhages about $10 million in guaranteed salary from games missed due

to injury alone. This makes fatigue, which directly relates to the twin

dangers of overexertion and soft-tissue damage, a chief threat to

playoff chances and literal fortunes.

But

with a big enough cache of data? A training staff could generate

algorithmically individualized prescriptions for rest and movement. It

could act pre-emptively, based on probability on top of past results.

“The more we can objectify what guys are doing,” Lyles says, “the more

accurately we can make recommendations or change what we do.”

Change

what they do — as in benching a starter before he suffers a projected

injury. Or trading him away for that same reason. Or cutting a backup

because of a suspiciously consistent spike in fatigue level after 2 in

the morning on road trips. In which case each player should answer a

question that everyone, regardless of occupation, might soon consider

for themselves: Would you be better served, economically, by your

employer’s knowing more or less?

“They’ll

bring guys in and work them out and be able to see if they’re at a

bigger risk to hurt their knee or whatever,” says Mavericks forward

Brandan Wright.

So when it comes to contract negotiations?

“Honestly, I think it’ll hurt guys,” Wright continues. “I think that’s where it’s headed.”

THE

SPECTRUM OF NBA lifestyles is contained within one 12-foot stretch of

the Heat locker room on a March afternoon last season. On one end, Ray

Allen is explaining how he can no longer drink soda without gagging.

Seriously. The 39-year-old has gone paleo, meaning that the guard eats

mostly lean meats, fish, nuts, vegetables and fruit. All of three

lockers away stands 25-year-old journeyman Michael Beasley, whose

culinary approach involves emptying a 41-ounce bag of Tropical Skittles

into his mouth like a cement mixer filling a ditch.

Allen

eagerly embraces food as fuel for the machine. But in the tradition of

fellow pros such as Pistons forward Caron Butler — who once kept six

fridges full of Mountain Dew at home and drank a liter of it over the

course of every game — Beasley might be an equally established

basketball archetype. Which is conspicuously suboptimal.

“A

lot of guys think they can get away with it,” says Graham, the

Grizzlies’ trainer. “I’ll still get bitched at because I’m like, ‘I’m

not giving you chicken wings.'”

What

players choose to put inside their bodies has long been an agenda item

inside locker rooms. Many teams, in fact, supply meals at work. Sixers

trainer Kevin Johnson even organizes color-coded eating groups, sorted

by whose weight needs to rise (red), maintain (white) or drop (blue).

But the precision of any dietary profile is hampered without knowledge

of the way particular foods interact with particular bodies. And the

barrier to that information is the drawing of blood: a ubiquitous

practice in the English Premier League but one typically found in

American sports only as part of lab work for a regular physical.

Unless,

of course, you happen to play for a team like the Mavericks. “I think

the smartest thing we do for health from a data perspective,” says

Cuban, “is take ongoing assessments and even blood tests so we have a

baseline for each individual that we can monitor for any abnormalities.

When someone is ill, we know what their numbers should be.”

The

Mavs are adamant: They have not done — or asked their players to do —

anything illicit in the administration of these tests and the handling

of the resulting samples. Still, granting any extra permission to a vein

requires trust that an employer will analyze only what you ask them to

detect. It requires trust that possible financial incentives to run

in-season tests for a battery of performance-related substances and

conditions — anything from marijuana to hormones to herpes — will be

ignored. “I’m not saying it’s bad for a topflight athlete to be

monitored,” says Caplan, the NYU bioethicist. “But a team physician, I’m

constantly reminded, is conflicted.”

When

asked by ESPN to elaborate on blood analysis, Cuban declined further

comment. But interviews with several Dallas players indicate that the

team’s expanded testing policy is neither obvious nor rosterwide. Guard

Devin Harris recalls giving blood only in the preseason as part of the

standard team physical; perhaps by design, other plasma-related details

remain vague. “I don’t know what they do with it once they have it, but

they definitely take it,” Harris says. “And I know they talked about

taking blood throughout the season for certain stuff.”

In

the field of nutritional analysis, the payoff for a blood draw comes

when a company such as Cell Science Systems — in attendance at the

NBSCA vendor show — generates a one-page, color-coded report that

indicates whether a player has any debilitating food allergies or

sensitivities to any of 100 specific foods. A universe of dining threats

is identified. A parallel test can also be run for allergies to tattoo

ink, which one Western Conference executive says were discovered in the

case of at least one unknowingly poison-decorated player.

THERE

IS ANOTHER, decidedly less generous view of where this road goes,

however. And one day last spring, after logging 13 years in the league, a

teammate of Allen and Beasley declares that the increase in biological

testing played a role in his decision to bow out of the business

altogether. “I think all fluids will be extracted in five years,”

forward Shane Battier says, three months before officially announcing

his retirement. “I’m glad I’m done.” Battier grants that certain

archetypes — your Allens, your Iguodalas — might be perfectly willing

to revamp their private lives in the service of basketball. But, he

continues, “big data is scary because you don’t know where it’s going

and who’s seen it. I’m not saying that they’d sell research to anyone,

but I don’t trust where my blood sample will end up and what eyes will

look at it and what people outside the NBA will know about it.”

Mind

you: This is Shane Battier talking, a 36-year-old guy whose vices

lately include pizza and a carafe of Scarecrow cabernet before bed; he’s

hardly the type of libertine to employ a Whizzinator to pass a drug

test. Regardless, the very notion of evading detection may soon be

obsolete. Dr. Saxon, of USC’s Center for Body Computing, is in the

planning stages of an invention that would render the Whizzinator-esque

technologies moot. Her vision? “Minimally invasive implantables,” Saxon

says, sounding genuinely excited. “Injectable, stays in the body for a

year or two. No fuss.” She can imagine the device feeding key biometric

information to your phone. Automated directions — the equivalent of

your new car telling you to fill up the tank — would then pop up as

alerts.

“If

they ask me to put a chip in my body, I don’t know about that,” Brandan

Wright says. “I don’t want to be a complete lab rat. I already feel

like one now. I don’t want to take it to the next level.” Or, as

Mavericks center Tyson Chandler, who won a championship with Dallas in

2011, puts it, “I’m not down with the alien stuff.” Chandler, 32, might

well retire before the “alien stuff” comes to pass. But if so, he’ll

likely have to do so soon.

“We

want to be one step beyond what anyone else is doing,” says Kings owner

Vivek Ranadive, whose personal fortune was built on the comprehensive

digitization of Wall Street. “Amazingly, what banks and trading floors

were 20 years ago, sports is now. The stakes are huge, and we can act

quickly.” Just listen to his GM, who is thinking far deeper than mere

skin. “The holy grail,” D’Alessandro says, “is sequencing and

understanding the genome. And how that relates to pro athletes on an

injury basis and who’s naturally good at certain sports.” As part of his

mandate with the Kings, he’s consulted scientists about one day

building a vast predraft database of player DNA — not just for

evaluation but for gauging injury risks and prevention. “You wouldn’t

have to be identified as a person,” he says, “you could be identified as

a number. I don’t suspect this will happen in our lifetimes. But the

way things have proliferated scientifically? Maybe it will.”

History

predicts serious pushback. In 2005, Alan Milstein represented Eddy

Curry against the Bulls, whose management wanted the center to submit to

genetic screening because of an irregular heartbeat. (Curry was

eventually traded to the Knicks, bypassing the issue.) The core

objection then, as now, was that genetic markers are not actual proof of

alcoholism, or Alzheimer’s, or cancer; they just signal greater odds of

developing those conditions. In fact, as of the 2008 passing of the

Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act, it is illegal for employers

to discriminate based on genetic information for that very reason.

Choosing to privilege reality over probability in that way, Milstein

notes, “was one of the few situations where Congress was actually

unanimous.”

In

their defense, NBA execs, team staffers and inventors do seem to

recognize these fears and offer counterarguments without being prompted.

Graham stresses that his interest as a trainer isn’t to find out how

his players entertain themselves at night, although that information may

well cross his transom — it’s to make them healthier and maximize

their careers. Holsopple, meanwhile, goes so far as to make Mavericks

players an explicit promise before sensitive monitoring takes place. “I

tell them that nobody sees the data but me and the people directly on

staff that work for me,” he says. The coaching staff, on the other hand,

“will get what they need to make decisions as coaches. But we will not

give them the things that players can be judged upon.”

Such

is the line, precarious as it is, that NBA teams are pledging to walk.

And such is the line that players, whose union will have biometrics on

its list of priorities during collective-bargaining-agreement talks in

2017, might ultimately refuse. But to hear the proponents of this

revolution tell it, they’re not so much sprinting toward Orwell as they

are grinding their way to incremental improvements. “That’s what the

reality is,” Lyles says. “We want to fine-tune things. If we do minor,

little tweaks here and there, maybe a guy doesn’t pull his hamstring.”

Or maybe, at the end of the fourth quarter, a foul defending a

game-winning shot instead becomes a block.

That

much optimization, the upside of so much technocracy, is the carrot

currently incentivizing the 30-year-old Iguodala as he staves off

departure from the game he dearly loves. In the meantime? “I just hope

we don’t become robots,” Iguodala says, “where they’re feeding us the

same thing, every day, and then it’s time to flip the switch and go to

sleep.”

That, after all, would be a different game entirely.

allow our cells to divide without dropping genes essential for life. In

this way, they are prime indicators of aging. They have been compared

to the aglets or plastic tips found at the ends of shoelaces or the wire

nuts used to protect and hold spliced electrical wires together. These

DNA sequences are responsible for what has been termed the Hayflick

Limit; the top number of divisions a human cell can have before it stops

replicating, becoming senescent or apoptotic. This process actually

protects us from unrestrained cellular division and, potentially, from

cancer.

become shorter over time with recurring replication as well as from

oxidative stress and can only be replenished via telomerase enzyme

adding back these telomeric repeats to the ends of the chromosome. Lack

of this enzyme allows inordinate telomeric shortening associated with

rapid aging and aging related health challenges. They act as a biomarker

of aging, sort of a cellular clock.

telomeres have also been linked to cardiovascular disease, some

cancers, osteoporosis, dementia, diabetes, and other chronic

degenerative diseases of aging conditions.

test is designed for anyone interested in optimal health, age

management and in knowing their telomere length as it relates to being

within or outside the normal reference range for their chronological

age.

shortened telomere length may be indicative of some chronic

degenerative medical issue occurring and possibly accelerated aging.

Telomere shortening is a dynamic process. Since telomeres respond

positively to improved dietary and lifestyle choices as well as

decreased oxidative stress knowing where their telomere sits in regards

to reference range will allow those with shorter telomeres for their age

to have the potential to change their lives, retard the hastened rate

of their telomeres shortening and potentially extend their lifespan.

Ogami, Yoshihiro Ikura, Masahiko Ohsawa, Toshihiko Matsuo, Soichiro

Kayo, Noriko Yoshimi, Eishu Hai, Nobuyuki Shirai, Shoichi Ehara, Ryushi

Komatsu, Takahiko,Naruko and Makiko Ueda