Ophthalmic surgeons can expect their cataract patients to complain about the high cost of postop medications. Staff time is lost on brand vs. generic discussions, insurance coverage concerns, frequency and duration of treatment questions, and renewals. Tech resources are devoured in determining exactly which drugs were received and how they are being used because these rarely coincide with the scripts written.

Approximately 3 months and 500 patients later, the patients, staff and surgeon are happier with dropless cataract surgery. No more emergency pages for medication clarification, no more requests for a suitable generic, no more time wasted looking through a patient’s possessions to determine the actual name of the drops they are using, and no more explaining that we do not have free samples to give.

I have put video of my first cases on the Internet, and while it has not gone viral, there is considerable interest. I believe it is only a matter of time before patients insist on dropless cataract surgery in the same way they demand custom or bladeless LASIK. In fact, Imprimis Pharmaceuticals, the company that acquired the intellectual property in August 2013 for the special patent-pending blend of antibiotics and steroids, has launched a “GoDropless” campaign.

Jim Gills, Doug Koch, Stewart Galloway and others pioneered the trail, and I am very happy to follow. There is a very short learning curve to this technique. Liegner suggests walking the cannula out beyond the capsule, tapping it gently as you proceed. I find it best to visualize the anatomy while the eye is oriented orthogonally. One caveat is that aiming too far out will generate some mild patient discomfort and some annoying but self-limited bleeding. I find it helpful to make certain the patient is cooperative before this maneuver. It is important to make sure the cannula is well secured, there are no bubbles in the syringe and you have more than 0.2 cc of medication. In fact, I prefer to use the same amount in the syringe each time.

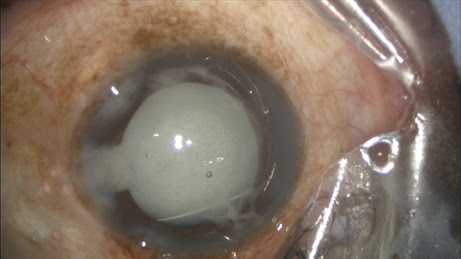

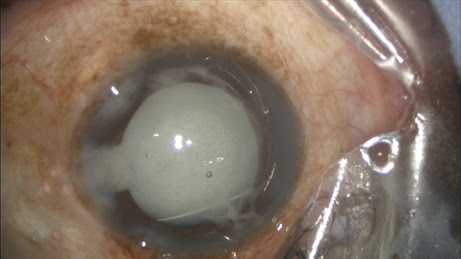

The surgeon must be comfortable watching a perfect red reflex become obscured. This cloud dissipates quickly; few patients will notice it and even fewer will complain. There were only a few reports of floaters or clouds postoperatively, and most patients were comforted to know that it was “just the medicine.” The first thing you notice on postoperative day 1 is that there is an unexpected pause at the end of the examination. In the same way LASIK patients reach for their glasses for the first few weeks after surgery, you will have an instinctual

desire to remind the patient to use drops. This awkwardness passes easily.

My staff and I made absolutely no effort to avoid adding a steroid if needed. Any patient who had cystoid macular edema in the other eye or those with any degree of corneal edema got a steroid on day 1. Any patients with even modest complaints of photophobia, redness or foreign body sensation, as well as those with ciliary flush, were treated. I added steroids to an uncomplicated post-graft cataract but did not use steroids in a few cases with planned vitrectomies and sutured posterior chamber IOLs.

After IOL implantation, while dispersive viscoelastic fills the anterior chamber, a 27-gauge Knolle cannula on a 1 cc tuberculin syringe is inserted behind the iris and above the peripheral anterior capsule. Once the cannula is advanced through the zonules, 0.2 cc of TriMoxiVanc is injected into the retrozonular space of Petit. A slow but steady motion of 2 to 4 seconds is required. During this time, most of the viscoelastic exits the eye. Residual viscoelastic is removed through irrigation and aspiration, followed by stromal hydration and limbal relaxing incisions as needed. This technique is applicable to femtosecond laser-assisted cataract surgery as well as conventional phacoemulsification. The antibiotic-steroid combination is seen behind the implant, obscuring the red reflex. Eighty-six percent of my first 500 patients required no postoperative drops. Pressure spikes, vitreous loss, bleeding and visual complaints are rare, transient or entirely absent.

Images: Lewis JS

—–

A case for dropless cataract surgery

A single prophylactic injection is gaining growing support.

BY JERRY HELZNER, SENIOR EDITOR

Cataract surgeon Jeffrey T. Liegner, MD, is once again on a mission. The former Air Force flight surgeon, whose practice is Eye Care Northwest in Sparta, N.J., aims to convince his colleagues that a single intravitreal injection of a steroid-antibiotic combination, delivered intraoperatively, can replace the traditional patient-administered prophylaxis of antibiotic eyedrops.

Dr. Liegner estimates he has safely performed 4,000 cataract operations with the single-injection approach. The advantages of this method, he says, comes down to “The Three Cs” — cost, compliance and convenience.

THE THREE CS

Cost

“The cost to the patient of eyedrops has become an increasingly critical issue, running to hundreds of dollars in out-of-pocket expense,” says Dr. Liegner, noting that in recent years higher co-pays, more limited formularies and restricted availability of samples have all contributed to the costs the patient bears.

“We were running into distracting pre-authorizations and unannounced substitutions of drugs, which creates more work for the doctors and less protection for the patient,” he says. “In 2010, I recognized that an alternative to topical antibiotics and steroids was becoming more and more important to the practicing eye surgeon. I began to query ASCRS members to see if any of them thought the same way and I found Dr. Kevin Scripture in Indiana who had been using an antibiotic-steroid combination he had been getting from a compounding pharmacy. That’s when I started my own search for a cost-effective stable and consistent combination of this type.”

Compliance

The single injection eliminates compliance issues, says Dr. Liegner. “It is a no-brainer,” he says. “The injection effectively inoculates the patient against infection. I don’t have to worry about it even if the patient is a charity case or one I see during an overseas mission and never see again.”

In his regular practice, he has encountered patients with so-called “eyedrop phobia” who cannot — or will not— self-administer eyedrops. He also notes difficulties that many patients have in instilling eyedrops effectively. Other patients may forget to adhere to the demanding postoperative regimen for using the drops.

“We don’t have to worry about any of those issues,” says Dr. Liegner. “I cannot remember a patient who requested drops after I explained the single injection to them.”

Convenience

“The single injection is more convenient for everyone involved in the procedure, including the surgeon, the patient, the office staff and the ASC staff,” says Dr. Liegner. “Just the time spent giving the patient the instructions for using the drops is well worth saving. The ASC is a high-cost environment, and I found we can save four minutes a case by bypassing the drops. With 20 cases a day, we are saving real money.”

Dr. Liegner says some surgeons may be wary that injecting a steroid (triamcinolone) could cause elevated IOP but he has not found that to be the case.

“The combination I use today is triamcinolone acetonide combined with moxifloxacin hydrochloride and vancomycin,” says Dr. Liegner. “With the 2.5 to 3 mg of triamcinolone I use, the incidence of elevated IOP is near zero.”

Growing interest in single injection

Though Dr. Liegner estimates that only about 50 cataract surgeons are currently routinely using single-injection prophylaxis, he confidently predicts that the number will rise sharply in the near future.

Video of combined steroid-antibiotic IVI procedure

“I am getting calls every day from the United States and overseas asking for information and advice on adopting the single injection,” he says. “Another cataract surgeon, Dr. James Lewis of Elkins Park, Pa., has also been giving presentations at meetings and noting all the advantages he has found with the single injection.”

In February, Dr. Lewis reviewed his successful use of single-injection prophylaxis and his transzonular administration technique in more than 400 cases at the American-European Congress of Ophthalmic Surgery meeting in Aspen, Colo.

“Experience with this compound now exceeds 14,000 procedures,” says Dr. Lewis. “Fewer than 10% of patients require steroid rescue at some point in their postoperative management.”

Because the FDA does not require formal studies of these types of combination drugs, the experiences and insights individual surgeons such as Drs. Lewis and Liegner provide can be valuable in driving wider adoption.

The Imprimis factor

What Dr. Liegner believes will most spur adoption of the single injection is the recent entrance of the drug development company Imprimis Pharmaceuticals (San Diego) into the arena.

Imprimis sees itself as a pharmaceutical hybrid, marrying the high-quality manufacturing standards of a traditional drug company with the ability of a compounding pharmacy to innovate and handle individual orders such as the steroid-antibiotic combinations.

“What Imprimis brings to the equation is the manufacturing, distribution and marketing skills that will bring the single injection into widespread acceptance,” says Dr. Liegner, who has signed on as a consultant to Imprimis.

Commercializing the combination

When Dr. Liegner began his own search for a compounding pharmacy that could produce a safe and effective steroid-antibiotic combination for use in cataract surgery, he first went to Pharmacy Creations (Randolph, N.J), which is accredited by the Pharmacy Compounding Accreditation Board and already had a relationship with his practice.

“We had obtained other products from Pharmacy Creations and I knew they were very much involved with national policy on accreditation and good manufacturing procedures,” says Dr. Liegner. “I visited them to film their process for my own review and due diligence.”

The first product Dr. Liegner obtained from Pharmacy Creations was a combination of triamcinolone and moxifloxacin (TriMoxi) that he used on every cataract surgery case and that Dr. Scripture also adopted. It took the compounder another year to get stable vancomycin into the mix.

“Once that occurred in 2011, I have used [TriMoxi+Vancomycin] on every cataract and intraocular procedure since,” says Dr. Liegner.

Seeking wide adoption

Imprimis made its initial move to commercialize the TriMoxi+Vancomycin combination by acquiring Pharmacy Creations in February.

“Our goal is to eventually have three to five high-quality manufacturing sites around the country to produce and distribute drugs that are brought to us by doctors and other innovators,” says Mark Baum, CEO of Imprimis. “We are putting an initial focus on ophthalmology but we are also looking at drugs for other specialties.”

Reaching critical mass

Dr. Liegner is certain that single-injection prophylaxis is an idea whose time has come. He sees all the elements now coming together to convert thousands of cataract surgeons to the concept.

“For awhile, we were just a few isolated cataract surgeons raising our hands, jumping up and down to be recognized,” he says. “Now, we are reaching the critical mass that will get the attention of cataract surgeons everywhere.”

My pearls for using TriMoxi+Vancomycin

A bit of practice makes for perfect technique.

BY JEFFREY T. LIEGNER, MD

I have assembled a number of pearls that will help the surgeon gain assurance with using single-injection prophylaxis.

Basic advantages of TriMoxi+Vancomycin

TriMoxi+Vancomycin, or, as I call it, TriMoxiVanc, comes in a 1-ml single-dose vial of preservative-free triamcinolone 15 mg/ml with moxifloxacin 1 mg/ml and vancomycin 10 mg/ml properly assembled, buffered and stabilized for intraocular injection. The product will be distributed nationally through Imprimis Pharmaceuticals (San Diego) under the stringent industry standards for pharmaceutical production.

TriMoxiVanc arrives already mixed into solution ready for draw and injection. It has a long stable shelf life with proven intraocular tissue compatibility.

TriMoxiVanc offers a significant advantage to the surgeon and ASC, with minimum distractions on the surgical field, compliance with Medicare requirements regarding compounding and single dosing in an ASC, with an acceptable cost while avoiding the obligation and documentation for patient counseling — and associated employee time costs — that eye drops and the associated compliance issues involve.

The injection procedure

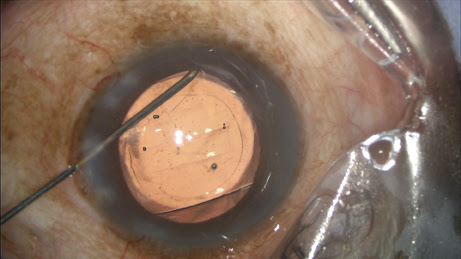

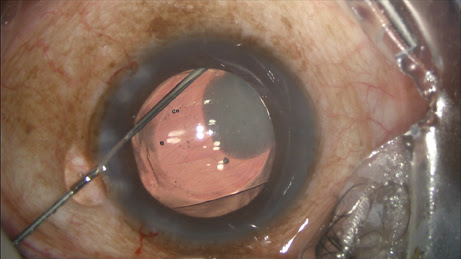

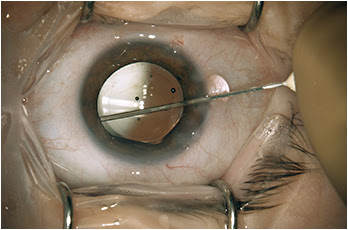

The circulating nurse transfers the contents of the vial onto the sterile field directly into a tuberculin syringe drawn up by the surgical technician, which is placed on a 27-gauge Knolle hydrodissection cannula (Katena, Denville, N.J.). I inject approximately 0.2 ml, leaving some additional TriMoxiVanc available for a sub-tenons supplement in rare circumstances (

Figure 1).

Figure 1: The surgeon performs the transzonular TriMoxi+Vancomycin injection using a 27-gauge hydrodissection cannula.

COURTESY: JAMES S. LEWIS, MD

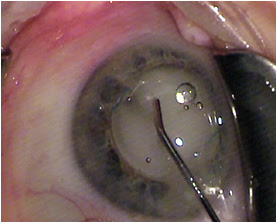

During my viscoelastic placement prior to IOL implantation, in addition to inflating the capsular bag, I will add some extra viscoeleastic under the iris inferionasally. After I insert the IOL, I enter the Knolle cannula through the primary keratotomy wound and pass it along the surface of the capsule, with visible tenting until reaching the equator, upon which the capsular tenting ends, indicating arrival at the zonules. A slight posterior rotation of the cannula tip and depressive movement posterior — without any visible capsule movement — confirms proper placement (

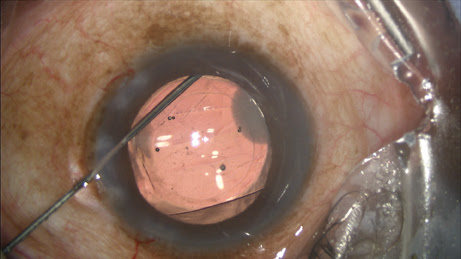

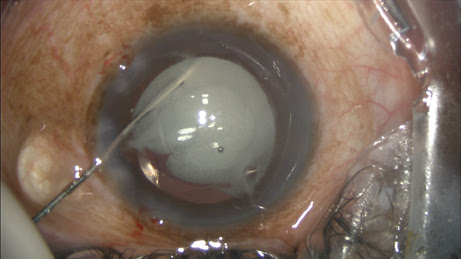

Figure 2).

Figure 2: Immediately after injecting the TriMoxi+Vancomycin mixture into the anterior vitreous through the zonules, the surgeon withdraws the cannula.

COURTESY: JEFFREY T. LIEGNER, MD

Sometimes I perceive a distinctive “pop” as the cannula tip penetrates a dense group of zonules. Other times there is no indication other than simply moving the cannula more posterior (deeper) without altering the visible capsule. My observational experience with ECP, including careful inspection of zonules, confirms the density of zonules is highly variable, yet the cannula weaves through the “wires” easily, never causing zonular injury or dehiscence.

Toric IOL alignment can be initially different, since the familiar red reflex used to visualize the alignment tic marks is replaced with a white reflex. Surgeons will quickly learn to visualize directly the tic marks on the optic more than seeing them in the red reflex.

Perfecting the injection technique

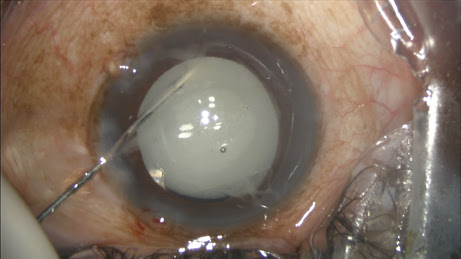

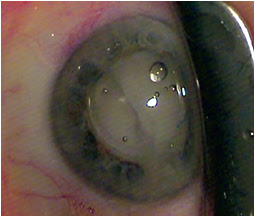

Most of the challenge in learning this technique, which is fundamentally a blind pass behind the iris, comes with watching and interpreting the appearance of the anterior capsule as the cannula slips radially outward and over it toward the zonules. The cannula easily passes into the zonules, and the injection should proceed slowly, filling the posterior space with added volume. About 75% of the time you see the plume of drug into the vitreous (

Figure 3).

Figure 3: With the IOL and the TriMoxi+Vancomycin in their proper positions, some product is shown tracking toward the wound along the exit path of the cannula.

COURTESY OF JEFFREY T. LIEGNER, MD

With experience, even a small pupil with a post-phaco constricted iris does not prevent transzonular injection. My first attempts were 60% successful, and quickly became 100% after three or four surgery days of practice.

I have never wrenched or torn zonules in such a way as to create a perceived or clinically significant zonular dialysis. Even with vigilance for an unplanned patient-commanded eye movement, it just hasn’t happened. In the video I have posted, the zonules seem to take some stretching without breaking.

Clues and signs to watch

During injection, the posterior capsule and IOL complex will rise accordingly (a helpful clue), and viscoelastic will exit the main wound. If I inadvertently inject anterior to the zonules (not into the vitreous), TriMoxiVanc will either reflux into the visible anterior chamber, or remain hidden under the iris around the perimeter of the equator.

The viscoelastic will eject, replaced by the steroid-antibiotic mixture, but the capsule does not rise. You will discover this upon irrigation and aspiration (I/A) removal of viscoelastic, when the volume of mixture is swept out of the angle.

A small hyperopic eye already has a crowded anterior chamber, even after removal of the natural lens, and adding an additional 0.2 ml of volume to the vitreous — after phaco irrigation adds some vitreous hydration— will make the anterior chamber even more shallow. Entering the primary wound with the cannula at a flat angle (parallel to the iris) is better than having a steep inclining angle, since a flat orientation discourages rapid viscoelastic exiting the wound.

Only occasionally does an IFIS issue result in a iris prolapse problem (drawn up to the wound with viscoelastic egress) when the vitreous volume expands. If I anticipate it, I will pass the cannula through the paracentesis instead of the main wound to deliver the drugs. Even with my in-the-bag piggyback multifocal IOL/toric implants, the anterior chamber volume issue is rarely a problem after TriMoxi+Vancomycin injection.

The inferior vitreous as your TriMoxiVanc destination is preferable, as this creates any floaters visible in the superior field. This allows for a consistent verbal message pre- and postoperatively from staff reminding the patient what to look for and why.

You can perform viscoelastic removal after the TriMoxiVanc injection as usual, with a bit more caution while under the IOL with I/A. The surgeon’s view can be unfamiliar because the vitreous and red reflex may now be white with steroid (or fluctuating white depending on globe-microscope angle), and it takes some getting used to.

The large plume of opaque steroids sitting behind the IOL would suggest the vision postoperatively would be an issue, but the mix is never obstructing, and the floaters are always peripheral. About 80% of patients report the floaters on postoperative day one, but only 20% notice them at postoperative week one.

Additional tips

My first day of surgery using this technique, I probably succeeded 40% to 60% of the time in getting through the zonules (four of 10 injections remained anterior to the zonules).

With more experience, I quickly learned the clues and hand movement to get that cannula through the zonules. Now I’m 100%.

Steroid-induced IOP rise. We rarely experience steroid-induced pressure rises postoperatively (maybe 1:100 or less), since the triamcinolone dose is 4 mg or less. Note that I do concurrent ECP if I obtain high IOPs preoperatively or see glaucoma damage, or if the patient is on glaucoma medications, so perhaps this skews the IOP issue in my favor.

Postoperative steroids. Supplemental postoperative topical steroids are infrequent (some one in 15 cases). One of four postoperative ECP patients require additional steroids topically — either prednisolone 1% or fluorometholone 0.1%, usually TID and not for long, and are usually not a topic until after postoperative week one.

If the patient does need steroids — rarely — because inflammation exceeds the TriMoxiVanc dose, signs will be slight redness (ciliary flush), good and stable vision, some photophobia, absence of globe or lid swelling, and quiet anterior chamber. This distinguishes rebound inflammation from true endophthalmitis, and the conversation quickly results in a phoned-in topical steroid prescription.

Consent. I do not provide a separate consent for this injection, but some others do. I also advise patients about the reasons for doing this, and the benefits to the patient; all patients have favored the injection in lieu of drops. Unexpectedly, I have also found that many patients have “drop anxiety” and will proceed with surgery once they hear that drops will not be required.

Postoperative floaters. Floaters do occur in the superior visual field sometimes after surgery, causing anxiety the first couple of days, but these fade quickly, often by the first week. Patients just need reassurance.

If you inadvertently inject a bubble of air with the mixture, this will slosh around superiorly, and so the patients will see the moving bubble in their inferior visual field, and they will perceive that the IOL is loose and rolling around down below their vision; I’ve learned that if a bubble gets transferred into the vitreous, I tell the patient to expect to see it, just to avoid the panic phone call that evening.

Ciliary body hemorrhage. A few times I have overreached the zonules and bumped a ciliary tooth, eliciting a small ciliary body hemorrhage and subsequently some blood seen inferiorly on postoperative day one. This microhyphema fades quickly, without an IOP issue. Based on ECP observations, a wide variety of toothy ciliary bodies exist, and some just beg to be bumped even with excellent cannula technique.

By the way, I use Healon GV (14 mg/ml, Abbott Medical Optics, Santa Ana, Calif.) or Optivisc (12 mg/ml, Anika Therapeutics, Bedford, Mass.) And I try not to hyperinflate the anterior chamber prior to IOL implantation.

Operative notes. All my reports for intraocular procedures include this sentence: “TriMoxiVanc 0.2 ml preparation (triamcinolone 15 mg/ml with moxifloxacin 1 mg/ml, vancomycin 10 mg/ml) was instilled through the inferior zonules after IOL insertion, prior to viscoelastic removal.”

Use of NSAIDS. I rarely use NSAIDs, but will occasionally. The CME rate seems much reduced with directly applied steroid into the vitreous, and so my use of NSAID is more responsive than prophylaxis. If a complication occurs (open capsule, vitrectomy required), I will stain vitreous and clean up as usual, add more TriMoxiVanc at the end behind the capsule, and then supplement with NSAID drops at the postoperative week one visit just for added protection against CME.

Vitreous tongue and strands. Rarely, a tongue of vitreous will be drawn back with the cannula through the zonules coming from the inferionasal delivery site. Since this vitreous strand is furthest from the wounds, it does not incarcerate and subsequently retracts, not to be seen on postoperative day one.

I have also occasionally seen vitreous strands come around intact zonules not associated with the cannula’s penetration, and have seen tiny lens particles in the anterior vitreous for no apparent reason. Some zonules are dense and others are permeable, inviting reflux of the TriMoxiVanc from any equatorial area, letting lens chips get posterior, or allowing strands of vitreous to slip forward with irrigation.

Potential role for ECP. I use ECP (and you will see some interesting video of the injection sequence using the ECP camera) and so I am very familiar now with the highly variable appearance of ciliary processes, zonules and lens equator dimensions. This ECP experience is not needed to perform TriMoxiVanc injections, but it does add texture to what we never see, what we presume is going on under that iris.

Reimbursement issues

Without going into too much detail, I can imagine that future bureaucratic review will look at the economics and expenditures of individual surgeons, and judge their cost burden on the insurer for intraocular procedures.

Because medications are covered with Medicare Part D and most commercial insurance plans, the surgeon who avoids expensive prescription eye drops and instead uses an intraocular injection at the time of surgery will have both outstanding patient evaluations and less overall cost to the third-party payers for the covered cataract procedure. This might create a competitive advantage for some, as insurers consider closed panels and economic credentialing, depending on their local market. I mention this possibility as I cringe.

Some payers will cover the ASC’s injection of triamcinolone into the vitreous, depending on negotiated contract rates and bundled agreements (or out-of-network payment behavior), and the ASC bills J3300 for the steroid and 67028 for the intravitreal injection (non-Medicare only).

ASC pricing for TriMoxiVanc single-dose vial is still reasonable and I have been advised that it will continue to be. With the changes in compounding pharmacy regulations, the pathway to national distribution have changed, and the very expensive FDA process has been edited to suit a faster market introduction and lower delivery cost. I have not been given solid details on anticipated pricing, only that it will be quite affordable. OM

|

About the Author

|

|

Jeffrey T. Liegner, MD, is in private practice at Eye Care Northwest in Sparta, N.J. His e-mail address is liegner@embarqmail.com.

Disclosure: Dr. Liegner is a consultant to Imprimis. He has no other relevant conflicts to disclose.

|

Ophthalmology Management, Volume: 18 , Issue: May 2014, page(s): 46, 48, 50, 51, 53, 71

——