Conjunctival lymphangiectasis

Conjunctival lymphangiectasis is an uncommon cuase of recurrent redness and conjunctival swelling (or chemosis).

Conjunctival Lymphangiectasia: A Report of 11 Cases and Review of Literature

- James Welch, BSc, MRCOphth1,

- Sathish Srinivasan, FRCS(Ed), FRCOphth1, 2, , ,

- Douglas Lyall,MRCOphth1,

- Fiona Roberts, MD, FRCPath3

Show more

Abstract

Conjunctival lymphangiectasia is an uncommon clinical condition in which there is dilatation of lymphatic channels in the bulbar conjunctiva. Conjunctival lymphangiectasia is a rarely appreciated ocular surface disorder that typically occurs as a secondary phenomenon in response to local lymphatic scarring or distal obstruction. Conjunctival lymphangiectasia can either be unilateral or bilateral with focal or diffuse bulbar chemosis. We present 11 cases of biopsy-proven conjunctival lymphangiectasia. Of the 11 cases, 3 presented with bilateral diffuse bulbar chemosis, 1 had diffuse unilateral chemosis, and the remaining 7 presented with focal (<90°) bulbar chemosis. Three of these cases had co-existing pterygium, and one case presented with focal bulbar chemosis and a conjunctival keratin horn. All underwent surgical excision of the involved conjunctiva, either with no graft (n = 6), combined with amniotic membrane transplant (n = 3), or combined with conjunctival autograft (n = 2).

Key words

- conjunctiva;

- lymphangiectasia;

- lymphatic vessels;

- chemosis;

- conjunctival cyst;

- surgical excision;

- amniotic membrane transplant;

- conjunctival autograft

Conjunctival lymphangiectasia is a rare condition in which the normal lymphatic vessels are dilated and prominent within the bulbar conjunctiva.20 It occurs in two forms: a diffuse enlargement of lymphatics that appears clinically as chemosis or focal dilated lymphatics that manifest as a cyst or a series of cysts (“string of pearls”).47 On clinical biomicroscopic examination, lymphangiectasia appears as channels containing clear fluid separated by diaphanous septate walls. In 1880 Leber used the term “Lymphangiectasia haemorrhagica conjunctivae” to describe a condition where the conjunctival lymphatics were filled with blood as the result of abnormal connections between conjunctival lymphatic and the conjunctival vascular system.55 We report a series of 11 cases of biopsy-proven conjunctival lymphangiectasia, discuss the distinctive histological characteristics of this condition, and review the literature on conjunctival lymphangiectasia and its differential diagnoses.

Patients and Methods

We reviewed the computerized flies at the regional Ocular Pathology Laboratory based at the Western Infirmary, Glasgow, Scotland, between January 1995 and December 2010. We identified and reviewed 11 cases with the diagnosis of conjunctival lymphangiectasia. We compared our findings with those reported in the literature.

Results

The patient characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

-

Table 1.Patient Characteristics

-

Case Age (years) Sex Date of Presentation Presenting Symptoms Co-morbidity Clinical Signs Clinical Diagnosis Histopathological Diagnosis Treatment Outcome 1 59 F Jun 2010 Irritation Preceding viral conjunctivitis Bilateral inferotemporal (<180°) diffuse chemosis Lymphangectasia Lymphangectasia with epithelial squamous metaplasia Bilateral excision with AMT No recurrence 2 53 M Sep 2010 Irritation Ipsilateral pterygium excision 2005 Focal temporal (<90°) unilateral chemosis Lymphangectasia Lymphangectasia with epithelial squamous metaplasia Excision with AMT Partial recurrence 3 49 M Sep 2010 Irritation Primary pterygium Focal nasal (<90°) unilateral chemosis Primary pterygium with cystic component Lymphangectasia with epithelial squamous metaplasia Excision with conj autograft No recurrence 4 48 M Oct 2010 Irritation Primary pterygium Focal nasal (<90°) unilateral chemosis Primary pterygium with cystic component Lymphangectasia with epithelial squamous metaplasia Excision with conj autograft No recurrence 5 47 F Oct 2010 Irritation

Recurrent epibulbar swellingNil Focal temporal (<90°) conjunctival thickening with keratinisation Conjunctival keratin horn Lymphangectasia with squamous metaplasia of epithelium and keratinization Direct excision No recurrence 6 65 M Feb 2010 Epibulbar swelling Nil Focal temporal (<90°) unilateral chemosis Superficial lymphangioma Lymphangectasia Direct excision Partial recurrence 7 33 F Dec 2010 Irritation Primary pterygium Focal temporal (<90°) unilateral chemosis Primary pterygium with cystic component Lymphangectasia with epitheial squamous metaplasia Excision with conj autograft No recurrence 8 68 M Dec 1995 Irritation Glaucoma

BlepharitisBilateral diffuse chemosis Allergic/toxic conjunctivitis Lymphangectasia Direct excision Recurrence 9 70 M Jun 2008 Irritation Ipsilateral senile ectropion Diffuse unilateral chemosis Not recorded Lymphangectasia Direct excision Partial recurrence 10 59 M Aug 2008 Irritation Nil Diffuse bilateral chemosis Allergic conjunctivitis Lymphangectasia Direct excision Recurrence 11 44 F Oct 2008 Irritation Nil Focal temporal (<90°) unilateral chemosis Inclusion cyst Lymphangectasia Direct excision Partial recurrence -

AMT = amniotic membrane transplantation; conj = conjunctival.

Illustrative Patient Reports

Patient 1

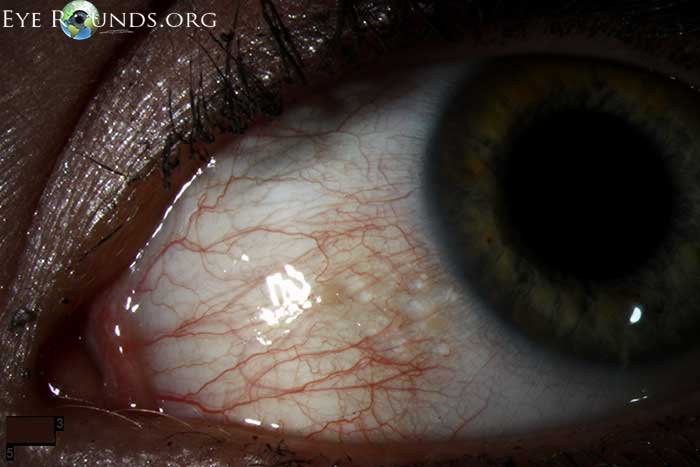

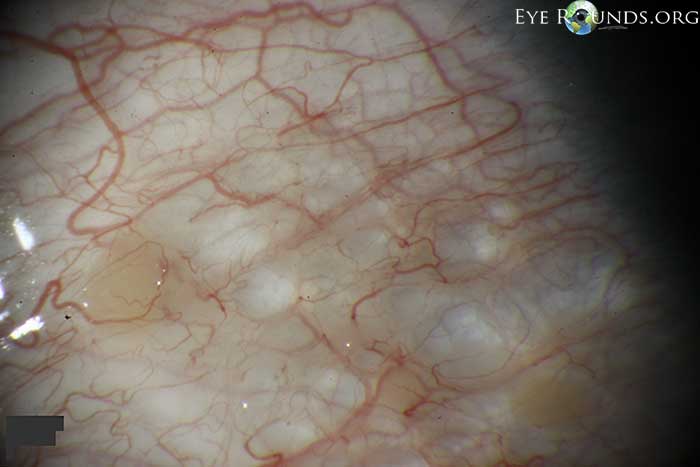

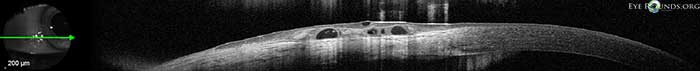

A 59-year-old woman presented with a one-year history of ocular irritation associated with persistent bilateral conjunctival swelling. This immediately followed an upper respiratory tract infection with associated conjunctivitis and was presumed to be of viral etiology. She had been treated with topical lubricants and corticosteroids with little benefit. Visual acuity was 20/20 in each eye. Slit lamp biomicroscopy revealed diffuse chemosis affecting the inferotemporal conjunctiva (Fig. 1 and Fig. 2). Anterior segment ocular coherence tomography was used to further delineate the abnormality (Fig. 3). A clinical diagnosis of conjunctival lymphangiectasia was suspected. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the orbits and head and neck were normal. Thyroid function tests, blood count, and serum biochemistry were normal. Excisional biopsy of the chemotic conjunctiva with amniotic membrane and fibrin glue was performed on each eye separated by an 8-week interval. Histologically both specimens demonstrated lymphangiectasia within the submucosa and squamous metaplasia of the surface epithelium. She remained asymptomatic during 12 months of follow-up with no evidence of recurrence.

Abstract

Conjunctival lymphangiectasia is an uncommon clinical condition in which there is dilatation of lymphatic channels in the bulbar conjunctiva. Conjunctival lymphangiectasia is a rarely appreciated ocular surface disorder that typically occurs as a secondary phenomenon in response to local lymphatic scarring or distal obstruction. Conjunctival lymphangiectasia can either be unilateral or bilateral with focal or diffuse bulbar chemosis. We present 11 cases of biopsy-proven conjunctival lymphangiectasia. Of the 11 cases, 3 presented with bilateral diffuse bulbar chemosis, 1 had diffuse unilateral chemosis, and the remaining 7 presented with focal (<90°) bulbar chemosis. Three of these cases had co-existing pterygium, and one case presented with focal bulbar chemosis and a conjunctival keratin horn. All underwent surgical excision of the involved conjunctiva, either with no graft (n = 6), combined with amniotic membrane transplant (n = 3), or combined with conjunctival autograft (n = 2).

Key words

- conjunctiva;

- lymphangiectasia;

- lymphatic vessels;

- chemosis;

- conjunctival cyst;

- surgical excision;

- amniotic membrane transplant;

- conjunctival autograft

Conjunctival lymphangiectasia is a rare condition in which the normal lymphatic vessels are dilated and prominent within the bulbar conjunctiva.20 It occurs in two forms: a diffuse enlargement of lymphatics that appears clinically as chemosis or focal dilated lymphatics that manifest as a cyst or a series of cysts (“string of pearls”).47 On clinical biomicroscopic examination, lymphangiectasia appears as channels containing clear fluid separated by diaphanous septate walls. In 1880 Leber used the term “Lymphangiectasia haemorrhagica conjunctivae” to describe a condition where the conjunctival lymphatics were filled with blood as the result of abnormal connections between conjunctival lymphatic and the conjunctival vascular system.55 We report a series of 11 cases of biopsy-proven conjunctival lymphangiectasia, discuss the distinctive histological characteristics of this condition, and review the literature on conjunctival lymphangiectasia and its differential diagnoses.

Patients and Methods

We reviewed the computerized flies at the regional Ocular Pathology Laboratory based at the Western Infirmary, Glasgow, Scotland, between January 1995 and December 2010. We identified and reviewed 11 cases with the diagnosis of conjunctival lymphangiectasia. We compared our findings with those reported in the literature.

Results

The patient characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

-

Table 1.Patient Characteristics

-

Case Age (years) Sex Date of Presentation Presenting Symptoms Co-morbidity Clinical Signs Clinical Diagnosis Histopathological Diagnosis Treatment Outcome 1 59 F Jun 2010 Irritation Preceding viral conjunctivitis Bilateral inferotemporal (<180°) diffuse chemosis Lymphangectasia Lymphangectasia with epithelial squamous metaplasia Bilateral excision with AMT No recurrence 2 53 M Sep 2010 Irritation Ipsilateral pterygium excision 2005 Focal temporal (<90°) unilateral chemosis Lymphangectasia Lymphangectasia with epithelial squamous metaplasia Excision with AMT Partial recurrence 3 49 M Sep 2010 Irritation Primary pterygium Focal nasal (<90°) unilateral chemosis Primary pterygium with cystic component Lymphangectasia with epithelial squamous metaplasia Excision with conj autograft No recurrence 4 48 M Oct 2010 Irritation Primary pterygium Focal nasal (<90°) unilateral chemosis Primary pterygium with cystic component Lymphangectasia with epithelial squamous metaplasia Excision with conj autograft No recurrence 5 47 F Oct 2010 Irritation

Recurrent epibulbar swellingNil Focal temporal (<90°) conjunctival thickening with keratinisation Conjunctival keratin horn Lymphangectasia with squamous metaplasia of epithelium and keratinization Direct excision No recurrence 6 65 M Feb 2010 Epibulbar swelling Nil Focal temporal (<90°) unilateral chemosis Superficial lymphangioma Lymphangectasia Direct excision Partial recurrence 7 33 F Dec 2010 Irritation Primary pterygium Focal temporal (<90°) unilateral chemosis Primary pterygium with cystic component Lymphangectasia with epitheial squamous metaplasia Excision with conj autograft No recurrence 8 68 M Dec 1995 Irritation Glaucoma

BlepharitisBilateral diffuse chemosis Allergic/toxic conjunctivitis Lymphangectasia Direct excision Recurrence 9 70 M Jun 2008 Irritation Ipsilateral senile ectropion Diffuse unilateral chemosis Not recorded Lymphangectasia Direct excision Partial recurrence 10 59 M Aug 2008 Irritation Nil Diffuse bilateral chemosis Allergic conjunctivitis Lymphangectasia Direct excision Recurrence 11 44 F Oct 2008 Irritation Nil Focal temporal (<90°) unilateral chemosis Inclusion cyst Lymphangectasia Direct excision Partial recurrence -

AMT = amniotic membrane transplantation; conj = conjunctival.

Illustrative Patient Reports

Patient 1

A 59-year-old woman presented with a one-year history of ocular irritation associated with persistent bilateral conjunctival swelling. This immediately followed an upper respiratory tract infection with associated conjunctivitis and was presumed to be of viral etiology. She had been treated with topical lubricants and corticosteroids with little benefit. Visual acuity was 20/20 in each eye. Slit lamp biomicroscopy revealed diffuse chemosis affecting the inferotemporal conjunctiva (Fig. 1 and Fig. 2). Anterior segment ocular coherence tomography was used to further delineate the abnormality (Fig. 3). A clinical diagnosis of conjunctival lymphangiectasia was suspected. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the orbits and head and neck were normal. Thyroid function tests, blood count, and serum biochemistry were normal. Excisional biopsy of the chemotic conjunctiva with amniotic membrane and fibrin glue was performed on each eye separated by an 8-week interval. Histologically both specimens demonstrated lymphangiectasia within the submucosa and squamous metaplasia of the surface epithelium. She remained asymptomatic during 12 months of follow-up with no evidence of recurrence.

-

Fig. 1.A: Slit lamp photograph of Patient 1, showing localized conjunctival swelling in the inferotemporal aspect of the bulbar conjunctiva in left eye (OS) (arrows). B: Slit lamp photograph of the same case, with fluorescein staining highlighting the area of bulbar conjunctival swelling in the OS.

Patient 2

A 53-year-old man presented with a 6-month history of ocular irritation and swelling OD. Five years before he had undergone primary nasal pterygium excision of the right eye with no conjunctival graft . Best corrected visual acuities were 20/20 in both eyes. The left eye was normal. Examination of the right eye revealed a cystic area located temporally within the bulbar conjunctiva and extending three clock hours. The clinical suspicion was conjunctival lymphangiectasia. MRI of the orbits and head and neck were normal. Thyroid function tests and serum biochemistry were within normal limits. Following informed consent he underwent excisional biopsy of the involved conjunctiva with fibrin-glue–assisted amniotic membrane transplantation. Histologically the excised conjunctiva showed numerous dilated lymphatics within the submucosa and squamous metaplasia of the surface epithelium. Two months following surgery, localized cystic chemosis developed temporal to the excised area. He has remained asymptomatic during 8 months of follow-up.

Patient 3

A 49-year-old man had a 2-year history of intermittent nasal bulbar redness and irritation in the left eye. He had been treated with topical corticosteroids during these episodes. Visual acuity was 20/20 in both eyes. The right eye was normal. Slit lamp biomicroscopy of the left eye revealed an area of thickened conjunctiva with cystic elements in the temporal bulbar conjunctiva that encroached onto the cornea in a wing-like fashion. Based on the clinical appearance a diagnosis of primary cystic pterygium was reached. He underwent excision of the pterygium with fibrin-glue–assisted conjunctival autograft. No sutures were used to secure the autograft. Histologically the specimen showed typical elastotic degeneration, with areas of lymphangiectasia within the submucosa. The patient has remained asymptomatic during 6 months of follow-up with no evidence of pterygium recurrence or chemosis.

Patient 4

A 48-year-old man had a 6-year history of intermittent nasal bulbar redness and irritation in the left eye. He used topical lubrications for symptomatic relief. Visual acuity was 20/20 in both eyes. The right eye was normal. Slit lamp biomicroscopy of the left eye revealed an extensive area of thickened conjunctiva that encroached onto the nasal cornea; a clinical diagnosis of primary pterygium was reached. Excision of the pterygium with fibrin-glue–assisted conjunctival autograft was performed. No sutures were used to secure the autograft. Histologically the specimen showed typical elastotic degeneration, with areas of lymphangiectasia within the submucosa (Fig. 4). The patient has remained asymptomatic during 8 months of follow-up with no evidence of pterygium recurrence or chemosis within the bulbar conjunctiva.

-

Fig. 4.A: Low-power view of pterygium associated with lymphangiectasia. There is a purplish area representing elastotic degeneration towards the right (arrow). The cluster of dilated lymphatics is seen towards the left of the picture (star) (hematoxylin and eosin; magnification ×20). B: High power showing area of lymphangiectasia. There is some chronic inflammation overlying the dilated vessels (star) (hematoxylin and eosin; magnification ×40).

Patient 5

A 47-year-old woman had a 2-year history of recurrent irritation and swelling on the outer aspect of her right eye. She wore monthly disposable silicone hydrogel contact lenses. Best corrected visual acuity was 20/20 in both eyes. Slit lamp biomicroscopy revealed localized cystic swelling involving the temporal bulbar conjunctiva of the right eye with an overlying keratin horn (Figs. 5A, 5B). She underwent excision biopsy of the lesion under topical anesthesia. On histological examination the excised conjunctiva showed marked lymphangiectasia within the submucosa and squamous metaplasia and keratinisation of the surface epithelium (Figs. 5C, 5D). The patient has remained asymptomatic during 8 months of follow-up with no evidence of recurrence.

-

Fig. 5.A: Slit lamp photograph of Patient 5 showing a localized conjunctival swelling in the inferotemporal aspect of the right eye with overlying cyst. B: High magnification slit lamp photograph of the same eye showing the keratin plug at the apex of the cyst. C: This patient presented with a keratin horn. Histology shows a large cystically dilated lymphatic channel (L) with several smaller lymphatic channels in the adjacent tissues. Presumably due to protrusion of the cyst and local trauma there is squamous metaplasia and localised hyperkeratosis (arrows) of the overlying mucosa (hematoxylin and eosin; magnification ×40). D: At higher power the cystically dilated lymphatic channel contains proteinaceous fluid and there are scattered smaller lymphatic channels (L) in the surrounding tissues. Inflammation (arrows) is also present in the stroma (hematoxylin and eosin; magnification ×100).

Patient 6

A 65-year-old man gave a 6-month history of swelling on the outer aspect of his left eye. He was treated with topical lubricants with limited effect. Visual acuity was 20/20 in both eyes. Examination of the right eye was normal. The left eye showed a localized area of superotemporal cystic chemosis of the bulbar conjunctiva in a classic “string of pearls” appearance (Fig. 6). Excisional biopsy of the involved conjunctiva was performed. Histological examination of the specimen showed lymphangiectasia within the submucosa and squamous metaplasia of the surface epithelium. The patient has remained asymptomatic during one year of follow-up despite de novo localized cystic chemosis temporal to the excised area.

-

Fig. 6.A: Slit lamp photograph of Patient 6 showing localized, linear bulbar conjunctival swelling with the classic “string of pearls” appearance involving the temporal bulbar conjunctiva of the left eye. B: Anterior segment ocular coherence tomography scan of the same eye showing multiple cystic spaces with the conjunctiva.

Patient 7

A 33-year-old woman presented with a 1-year history of persistent irritation and redness of the inner aspect of the right eye. She used topical lubrications for symptomatic relief. Visual acuity was 20/20 in both eyes. Slit lamp biomicroscopy revealed a primary nasal pterygium encroaching 2 mm onto the cornea. There was no associated chemosis. As she was symptomatic, she underwent pterygium excision with fibrin-glue–assisted conjunctival autograft. No sutures were used to secure the autograft. Histological examination of the specimen confirmed a pterygium with elastotic degeneration within the submucosa and squamous metaplasia of the surface epithelium (Fig. 7). There was accompanying lymphangiectasia. The patient has remained asymptomatic during 5 months of follow-up with no evidence of pterygium recurrence or chemosis.

-

Fig. 7.A: This specimen was removed as a pterygium and shows focal eosinophilic pink material in the superficial stroma (arrows) and dilated lymphatic channels (L) deep to this (hematoxylin and eosin; magnification ×40). B: The eosinophilic material is confirmed as degenerate elastic fibers (E) (elastica van Gieson; magnification ×20).

Histological Features

The lymphatic channels of the conjunctiva contain valves that allow for directed drainage towards the inner and outer canthi. Obstruction can occur in inflammatory and neoplastic disease. This obstruction leads to lymphangiectasia or, if extreme, lymphatic cysts. Excised tissue will show dilated channels lined by a flattened endothelium. The ultrastructural characteristics of ectatic lymphatic vessels do not differ significantly from a normal lymphatic vessel. The vessel is, however, dilated, and the surrounding lamina propria is often edematous, presumably because these dilated vessels leak. The channels may contain proteinaceous fluid or clusters of lymphocytes (Fig. 8A). This may be accompanied by squamous metaplasia and keratinisation of the overlying surface epithelium (Fig. 8B) as part of a reactive process related to local trauma. If necessary, dilated lymphatic channels can be differentiated from capillaries by immunohistochemical staining for D2-40, a sensitive and specific marker of lymphatic endothelium (Fig. 8C).29 The surrounding lamina propria may contain scattered inflammatory cells or show fibroblastic proliferation or scarring, supporting the secondary nature of this process.

-

Fig. 8.A: Conjunctival mucosa with numerous dilated lymphatic channels (L). These contain proteinaceous fluid in contrast to the capillaries (C). There is mild chronic inflammation in the stroma (arrows) (hematoxylin and eosin; magnification ×40). B: On higher power there is patchy squamous metaplasia of the surface epithelium (hematoxylin and eosin; magnification ×100). C: Immunohistochemical staining for D2-40 confirming dilatation of lymphatic channels (arrows) (D2-40; magnification ×200).

Discussion

The human lymphatic system, first described in 1627 by Gasper Aselli,30 functions to remove excess interstitial fluid and macromolecules from the extracellular space and transports this fluid through lymph nodes before returning it to the venous circulation.19 Despite its integral role in preserving tissue fluid homeostasis, the study of lymphatics remains at a rudimentary level when compared to blood vessels.101

Conjunctival interstitial tissue fluid enters through the initial lymphatic (blind-ended tubes that are made up of endothelial cells) located immediately under the epithelium. The cells are tethered to surrounding stroma by anchoring filaments that prevent the tubes from collapsing.14 The precise mechanism that drives fluid into these initial lymphatics has not yet been fully elucidated.102 We do know, however, that lymphatic flow is created by the development of fluid pressure gradients between the initial lymphatic and downstream collector channels.69 and 102 Unidirectional luminal valves are present throughout the lymphatic system and prevent backflow,22 but these valves may not be completely effective, as Shields et al reported a case of retrograde metastasis of a preauricular cutaneous melanoma to the ipsilateral conjunctival lymphatics.83

It was once thought that the conjunctivae were the only components of the globe and orbit to have a lymphatic drainage system; however, lymphatic tissue has been consistently found in the lacrimal gland and optic nerve in humans and in the orbital apex and extraocular muscles in other primates.30 and 82 The distinguishing electron microscopic features of initial lymphatics that permit differentiation from vascular capillaries are well characterized.14, 30 and 82 Both conjunctival and corneal lymphatics have been identified using in vivo confocal microscopy and show features morphologically distinct from adjacent blood vessels and discrepancies with respect to leukocyte flow velocities, yet some descriptions make no reference to bulbar conjunctival lymphatics at all.21 and 67

The organization of the conjunctival lymphatics has been delineated using vital dyes and is divided into several groups.60, 89 and 93 A pericorneal lymphatic ring (lymphatic circle of Teichmann) forms a dense plexus of tiny lymphatic vessels along the limbus measuring about 1 mm in size. These then coalesce as they leave the limbus, forming a system of larger radially orientated vessels. At between 4 to 8 mm behind the limbus, large collector channels run circumferentially (pericorneal lymphatic ring), and these receive lymph from the radial lymph vessels. It is thought that there are connections between the deep conjunctival venous plexus and the collector channels, and on occasion retrograde flow results in the lymphatic channel filling with blood (lymphangiectasia hemorrhagica). The collector channels drain into one or two trunks, and these drain towards the lateral and medial commissures, where they join the lymphatic outflow of the eyelids. 36 There are no conjunctival lymph nodes. 93 The subsequent drainage of the eyelid lymphatics was thought to be by two main groups of vessels. A medial group of lymphatic vessels drains the medial upper and lower eyelids and terminates in the ipsilateral submandibular lymph nodes; a lateral group of lymphatics drains the lateral ends of both eyelids and terminates in the ipsilateral superficial parotid lymph nodes. With the development of newer mapping modalities—namely, 99mTechnetium lymphoscintigraphy—there is an appreciation of variability in drainage patterns between individuals. 72 The majority of lymphatic basins are located in the parotid and anterior cervical nodes. 11 and 24

Recent advances in the field of molecular biology have permitted the identification of lymphatics from other than purely histological criteria.2 and 49 This has been driven by the appreciation of the important role that lymphatics play in tumor metastasis and inflammatory conditions such as transplant rejection.1, 39, 51 and 104Vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 3 (VEGFR-3), through it two ligands, VEGF-C and VEGF-D, is considered the major regulator of lymphangiogenesis.3, 49 and 95 Other molecular markers specific for lymphatic vessels include lymphatic vessel endothelium hyaluronic acid receptor and the novel monoclonal antibody D2-40.13 and 46

Genetic mapping of the autosomal dominant form of hereditary primary lymphedema (Milroy disease) has identified that the disease can be attributed to a point mutation that inactivates VEGFR-3 signaling.40 A murine model for this disease has been developed which has been used extensively to investigate the phenotypic consequences of deranged lymphangiogenesis.48 Primary lymphedema in humans, resulting in congenital conjunctival lymphangiectasia, has also been reported in Klippel-Trenaunay-Weber and Turner syndromes.8 and 75

Nevertheless, the vast majority of conjunctival lymphangiectasia cases seen in clinical practice are not congenital. Rather, they represent a secondary lymphedema following disruption or obstruction of lymphatic pathways by other disease processes or as a consequence of surgery or radiotherapy. Patients may present because of cosmetic concerns or, more frequently, local irritation from tear-film disturbances provoked by epibulbar irregularity.

The history must specifically elicit whether the patient is aware of a head or neck mass or has been treated for such tumors previously. Harris et al reported a series of six such patients, and although no cases of tumor recurrence at the primary site, regional nodes, or orbital apex were identified. Persistent chemosis was thought to represent surgery- and radiation-induced obstruction of lymphatic/venous outflow channels.36 Similarly, cosmetic blepharoplasties are a recognized precipitant of conjunctival lymphangiectasia.23, 47, 58 and 68 In situations where conjunctival swelling is associated with hemorrhage, it is important to establish whether this is recurrent and the time course over which the blood clears. Clearing is reported to occur in 2–4 days, but may take several weeks, revealing persistent, ectatic, sausage-like conjunctival lymph vessels.6, 54, 60 and 81

The history should identify medical conditions resulting in systemic hypoproteinemia (nephrotic syndrome, malnutrition), local venous hypertension (thyroid eye disease, orbital apex syndrome, cavernous sinus thrombosis, carotid-cavernous fistula), and increased vascular permeability (vasomotor instability, allergy), as all these can drive fluid into the interstitial compartment resulting in chemosis. Travel to West and Central Africa is relevant, as Loa Loa infestation can appear as sausage-like dilations within the conjunctiva.5

Examination to identify any local masses or lymphadenopathy within the head and neck is mandatory, and computerized tomography or MRI may be required. The laterality and location of the conjunctival swelling is determined. Experience suggests that lymphangiectasia is most likely to be located within the temporal conjunctiva or dependent when it is more extensive.47 and 60 Where blood is present within these vessels, some may exhibit a horizontal fluid level where they are only partially filled.60 A local cause of lymphatic obstruction can often be identified adjacent to the lymphangiectasia, in our experience typically a primary pterygium. Rarely is there active local inflammation identified in lymphangiectasia, with most eyes appearing white at initial presentation, presumably because the inciting inflammatory event causing lymphatic scarring has resolved.47 As seen in Patients 3 and 4, the finding of lymphangiectasia in relation to a pterygium supports the contention that inflammation and stromal changes disrupt the lymphatic drainage, resulting in localized dilatation. To exclude other causes of chemosis, baseline blood count, blood urea nitrogen, electrolytes, serum albumin, and thyroid function tests are routinely checked. Once diagnosed, lymphangiectasia can be a challenging condition to treat, as the nature of the preceding lymphatic obstruction can rarely be identified.

Several strategies to treat conjunctival lymphangiectasia have been described, typically reported as small case series. Direct excision of the affected conjunctiva can be successful.85, 92 and 93 Meisler et al described localized resection of all involved bulbar conjunctiva down to bare sclera.65 All patients remained asymptomatic and recurrence-free at one year. An earlier series where the lymphangiectasia was simply biopsied to facilitate tissue diagnosis, the chemosis persisted, implying that the whole lesion must be excised.47 Liquid nitrogen cryotherapy is effective; recurrences are common, but these are amenable to retreatment.27 and 28 Isolated reports detail other modalities, specifically fractionated beta-irradiation and carbon dioxide laser ablation.7, 44 and 91 In cases of lymphangiectasia haemorrhagica, both surgical excision and diathermy of the abnormal communication between the conjunctival vessels and lymphatics have been described.6, 15 and 57 A refinement of the thermal coagulation principle has been reported. Lochhead and Benjamin used an Argon laser to obliterate the junction between the blood vessel and lymphatic.60 Three patients were treated, the procedure was well tolerated, and no recurrences occurred during the follow-up period of one year.

Rarely, after procedures that involve extensive conjunctival manipulation such as blepharoplasty and scleral buckling, prolonged postoperative dependent bulbar chemosis occurs.9 and 62 Although none of these reports include conjunctival histopathology, it is likely that the chemosis develops in response to damage to local lymphatics.58 In many cases spontaneous resolution occurs, presumably due to lymphangiogenesis; however, the chemosis may be persistent.68 Enzer and Shorr emphasize that, in such situations, stretching of the inferior forniceal ligaments occurs, and these must be surgically reattached to the orbital floor if initial simple measures such as pressure patching fail.23 and 37 In our series we initially performed direct surgical excision; although more recently we have incorporated the use of cryopreserved amniotic membrane grafts. Wide experience has been reported with such grafts in the context of ocular surface reconstruction with excellent results.64 and 76 It should be appreciated that isolated conjunctival lymphangiectasia may be identified not infrequently during clinical examination. Often it is not symptomatic, but in a minority of cases it can be a cause of persistent ocular irritation. In such situations, many patients respond to topical steroids, which suppress conjunctival inflammation; only in those individiuals where chronic lymphatic scarring and ectasia supervenes is surgical intervention indicated.

With rare conditions such as lymphangiectasia, where there are no randomized controlled trials, it can be difficult to determine which surgical intervention has the best chance of success. We feel that our technique using amniotic membrane, which empirically attempts to minimize further local tissue trauma, has much to recommend it.

Differential Diagnosis

Epithelial Inclusion Cyst

Conjunctival inclusion cysts are common, accounting for 22.5% of all acquired epithelial lesions, and 80% of all cystic lesions, of the conjunctiva.32 The incidence is equal between men and women, with an average age of onset of 47 years.32 They are classified as primary or secondary, depending on their etiology. The primary or congenital inclusion cyst is usually located to the superomedial portion of the orbit and develops during the embryonal period as the result of separation of a portion of conjunctival epithelial cells.41 The secondary or acquired inclusion cyst is more prevalent than the primary cyst and is located most commonly in the superolateral aspect portion of the orbit. Acquired inclusion cysts form as the result of implantation of conjunctival epithelium underneath the stroma following injury or surgery, but may occur spontaneously by the amalgamation of mucosal folds that result from irregularly elevated surface epithelium in inflammatory conditions.84

Acquired inclusion cyst formation has been reported following surgery where the conjunctiva is disturbed, including strabismus surgery, vitreoretinal surgery, cataract surgery ,and sub-Tenon’s anesthesia.10, 70, 90,97 and 99 Spontaneous inclusion cyst formation has been reported in association with pterygia and in longstanding chronic vernal keratoconjunctivitis.52 and 56 The cysts may present many decades after the surgical procedure, particularly strabismus surgery.90 They can be unilocular or multilocular. Histopathogical examination reveals that the cysts are lined by non-keratinizing stratified epithelium with occasional goblet cells. There may be scattered chronic inflammatory cells within the substantia propria, and if the cyst is longstanding, foci of dystrophic calcification may be present. The cysts are filled with clear fluid that often contains desquamated cellular debris.87 Indications for removal include unacceptable cosmetic appearance, limitation in ocular motility, induced astigmatism, and ocular irritation.52, 90 and 97Excision biopsy is the standard, although cauterization at the slit-lamp and Nd:YAG laser ablation has been used successfully for acquired cysts.18, 38 and 53

Cystic Conjunctival Nevi

The conjunctival nevus is the most common melanocytic tumor of the conjunctiva and has a benign natural history, with less than 1% developing into malignant melanoma.87 A nevus typically becomes clinically apparent during the first or second decade of life as a discrete, variably pigmented, slightly elevated lesion that may contain fine, clear cysts.88

Histologically, the structure of conjunctival nevi is similar to those found on skin, namely junctional, compound, and subepithelial. The nevus tend to be well circumscribed, non-encapsulated with nests of benign melanocytes in the stroma near the basal layers of the epithelium. A unique feature of conjunctival nevi, distinct from skin nevi, is the presence of large number of epithelial nest and cysts.79 These cysts are found in 40–70% of all conjunctival naevi and are composed of a stratified squamous epithelial lining and occasional goblet cells.42 It is hypothesised that the epithelial tissue is dragged down as the initial junctional nevus descends into the substantia propria and becomes a compound nevus.26 With time the intraepithelial component of the nevus may be lost completely, and thus only the subepithelial component persists, resulting in a subepithelial nevus. Cysts are noted in 70% of compound nevi, 58% of subepithelial nevi, and 40% of junctional nevi.86 In children,conjunctival nevi excised because of documented rapid growth frequently show a marked local inflammatory infiltrate.103

Lymphangioma

Although a historically accepted term, lymphangioma literally implies a neoplasm of lymphatic origin, these lesions are hamartomatous malformations, however, and their anomalous morphogenesis does not produce true lymphatic channels.34

These lesions constitue a wide spectrum of malformations that are influenced when they occur during embryonic embryogenesis.43, 50 and 100 These can involve multiple orbital compartments, including both the palpebral and epibulbar conjunctiva.35, 45 and 78 Many are symptomatic because of mass effects, hemorrhage, and pain associated with acute enlargement.33 These vascular malformations typically become apparent in the first decade of life, although rarely they may manifest much later, with the oldest presentation being in a patient aged 79.35 There is a slight female preponderance.59

Histological analysis reveals an ill-defined collection of lymphatic channels infiltrating normal tissues without a capsule.35 The accumulation of vessels is more prominent than in lymphangiectasia. There is a variable amount of stroma showing evidence of smooth muscle, thereby belying a purely lymphatic lineage, hemosiderin-laden macrophages (if subject to repeated hemorrhages), and a variable lymphocytic component.59 In some cases the lymphocytic elements are arranged into lymphoid aggregates forming subendothelial follicular structures.96

Conjunctivochalasis

Conjunctivochalasis describes the condition where there is redundant, loose, non-edematous inferior bulbar conjunctiva interposed between the globe and the lower eyelid margin.66 It is invariably bilateral, although it may be asymmetric, being most prevalent in the elderly.61 Mechanical disruption of normal tear outflow occurs from interference by the redundant conjunctiva with the inferior tear meniscus and direct occlusion of the lower punctum.61 Patients complain of intermittent epiphora, ocular irritation or frank pain, and recurrent subconjunctival hemorrhage.71 Otaka and Kyu suggested that the redundant conjunctival folds were found at the lower-lid margin rather than the upper because of gravity.74

Meller and Tseng propose that chronic ocular surface inflammation causes the accumulation of collagenolytic enzymes in tears resulting from delayed tear clearance and may be linked to the development of redundant bulbar conjunctiva.66 A subsequent study by Watanabe et al did indeed find morphologic degenerative changes in the conjunctiva with fragmentation of elastic fibers and loss of collagen fibers in all cases, although there was no evidence of chronic inflammation.98 Instead they hypothesised that purely mechanical forces between the lid and conjunctiva impaired lymphatic flow resulting in microscopic lymphangiectasia, which in turn led to the development of conjunctivochalasis. Others have not found any evidence of lymphangiectasia in such patients, but did find chronic tissue inflammation in association with functional nasolacrimal blockage.12 and 16 Fraunfelder reported one case that presented with diffuse lymphangiectasia in the right eye and conjunctivochalasis in the left eye, demonstrating that these conditions can coexist.27

Seasonal and Perennial Allergic Conjunctivitis

Seasonal allergic conjunctivitis (SAC), or hay fever, is the most common form of ocular allergic disease and is associated with sensitization and exposure to environmental allergens, in particular grass and ragweed pollens.63 Perennial allergic conjunctivitis (PAC), typically triggered by house dust mites and animal dander, is considered a less severe variant of SAC characterized by year-round symptoms, but with seasonal exacerbations experienced by 79%.17 Both conditions have an onset in childhood or early adulthood with no sex predilection. Affected individuals often have a history of atopy.31 Symptoms are invariably bilateral,l but may be asymmetric and consist of red, itchy eyes, with associated burning discomfort and watery discharge. Both SAC and PAC are examples of a type 1 IgE-mediated hypersensitivity reaction. The primary inflammatory cells involved in ocular allergy are mast cells, which reside within the substantia propria.73

Clinical examination reveals mild conjunctival hyperemia with a papillary reaction. In severe cases there is chemosis as a result of increased tissue fluid, most marked in the bulbar and lower tarsal conjunctiva. This gives the eyes a characteristic glassy appearance. Although rarely performed in clinical practice, histological analysis of conjunctival specimens from SAC and PAC patients demonstrates increased numbers of mast cells in the stroma, and infrequently within the epithelium itself.4 There may be stromal edema and increased numbers of conjunctival goblet cells.63

Ataxia-telangectasia

Ataxia telangectasia (AT; Louis-Bar syndrome) is a rare autosomal recessive disorder characterized by early-onset progressive cerebellar ataxia, immunodeficiency, dysarthria, oculocutaneous telangiectasia, and abnormal ocular motility (nystagmus, pursuit and saccadic abnormalities, strabismus), and poor convergence and accommodation.25 In the United States the incidence has been reported as 1in 30,000 live births.94 The responsible gene, ATM (AT mutated), located on chromosome 11, was identified in 1995.80 The telangectasia are always bilateral and are most prominent on the interpalpebral conjunctiva.25These vessels increase in tortuosity and become progressively more dilated over the years.77Telangiectasia of the skin may subsequently develop; the regions most commonly affected are the malar eminence of the face and pinnae of the ear. Unlike lymphangiectasia conjunctivae hemorrhagica where the blood-filled vessels appear then clear within a matter of days, in AT they are persistent and progressive. The vascular changes appear to have no significant effect on ocular comfort in most patients, although some are photophobic.25 Histopathological analysis of bulbar conjunctival tissue from AT patients demonstrates increased numbers of blood vessels and greater variability in vessel caliber than control tissue from the ipsilateral inferior fornix.77

Summary

Conjunctival lymphangiectasia has received scant attention in the medical literature, yet incidental sausage-like conjunctival cystic lesions are not infrequently seen during anterior segment examination. These require no intervention unless they result in persistent ocular surface irritation that is refractory to topical anti-inflammatories and lubrication. The vast majority are thought to represent secondary lymphangiectasia, developing as a consequence of a prior inciting stimulus, resulting in persistent local lymphatic scarring or distal mechanical outflow obstruction. Typically the patient does not recall this preceding event, nor is it clinically apparent. True primary conjunctival lymphangiectasia is rare and is only seen where there is a generalized failure of lymphatic development, as a result of deranged VEGFR-3 signaling.

Method of Literature Search

A search of the PubMed database 1966–2010 was conducted using various combinations of the key wordsconjunctiva, lymphangiectasia, lymphangiectasis, lymphatics, chemosis, swelling, cyst, and hemorrhage. Articles in all languages were considered, provided that the non-English articles included English abstracts. Relevant articles that were cited in the reference lists of the retrieved articles were also included.

Disclosure

The authors reported no proprietary or commercial interest in any product mentioned or concept discussed in this article.

References

-

- 1

- M.G. Achen, B.K. McColl, S.A. Stacker

-

Focus on lymphangiogensis in tumor metastasis

-

Cancer Cell, 7 (2005), pp. 121–127

-

|

|

|

-

- 2

- K. Alitalo, T. Tammela, T.V. Petrova

-

Lymphangiogenesis in development and human disease

-

Nature, 438 (2005), pp. 946–953

-

|

|

-

- 3

- A. An, S.G. Rockson

-

The potential for molecular treatment strategies in lymphatic disease

-

Lymphat Res Biol, 2 (2004), pp. 173–181

-

|

|

-

- 4

- D.F. Anderson, J.D.A. Macleod, S.M. Baddeley, et al.

-

Seasonal allergic conjunctivitis is accompanied by increased mast cell numbers in the absence of leucocyte infiltration

-

Clin Exp Allergy, 27 (1997), pp. 1060–1066

-

|

|

-

- 5

- E. Ansari, L. Teye-Botchway, R. Taylor, et al.

-

Conjunctival lymphangioma. A can of worms?

-

Eye, 12 (1998), pp. 891–893

-

|

-

- 6

- P. Awdry

-

Lymphangiectasia haemorrhagica conjunctivae 1969

-

Br J Ophthalmol, 53 (1969), pp. 274–278

-

|

|

-

- 7

- S. Behrendt, H. Bernsmeier, G. Randzio

-

Fractioned beta-irradiation of the conjunctival lymphangioma

-

Ophthalmologica, 203 (1991), pp. 161–163

-

|

-

- 8

- M.J. Belliveau, S. Brownstein, W.B. Jackson, et al.

-

Bilateral conjunctival lymphangiectasia in Klippel-Trenaunay-Weber syndrome

-

Arch Ophthalmol, 127 (2009), pp. 1057–1058

-

|

|

-

- 9

- A.W. Biglan, A. Chang, D.A. Hiles

-

Prolapse of conjunctiva following external levator resection

-

Ophthalmic Surg, 9 (1980), pp. 581–583

-

|

-

- 10

- T. Bourcier, C. Monin, M. Baudrimont, et al.

-

Conjunctival inclusion cyst following pars plana vitrectomy

-

Arch Ophthalmol, 121 (2003), p. 1067

-

|

|

-

- 11

- G.W. Carlson, D.R. Murray, R. Greenlee, et al.

-

Management of malignant melanoma of the head and neck using dynamic lymphoscintigraphy and gamma probe-guided sentinel lymph node biopsy

-

Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg, 126 (2000), pp. 433–437

-

|

|

-

- 12

- D.G. Chan, I.C. Francis, M. Filipic, et al.

-

Clinicopathologic study of conjunctivochalasis

-

Cornea, 24 (2005), p. 634

-

|

|

-

- 13

- L. Chen, C. Cursifen, S. Barabino, et al.

-

Novel expression and characterization of lymphatic vessel endothelial hyaluronate receptor 1 (LYVE-1) by conjunctival cells

-

Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci, 64 (2005), pp. 4536–4540

-

|

|

-

- 14

- H.B. Collin

-

The ultrastructure of conjunctival lymphatic anchoring filaments

-

Exp Eye Res, 8 (1969), pp. 102–105

-

|

-

- 15

- H. Conrads, G. Kuhnhardt

-

Zur pathogenese der lymphangiectasia haemorrhagica conjunctivae

-

Klin Monatsbl Augenheilkd, 137 (1957), pp. 670–674

-

- 16

- S.T. Conway

-

Evaluation and management of functional nasolacrimal blockage: result of a survey of the American Society of Ophthalmic Plastic and Reconstructive surgery

-

Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg, 10 (1994), pp. 185–187

-

- 17

- J.K. Dart, R.J. Buckley, M. Monnickendan, et al.

-

Perennial allergic conjunctivitis: definition, clinical characteristics and prevalence. A comparison with seasonal allergic conjunctivitis

-

Trans Ophthalmol Soc UK, 105 (1986), pp. 513–520

-

|

-

- 18

- S. De Bustros, R.G. Michels

-

Treatment of acquired epithelial inclusion cyst of the conjunctiva sing the YAG laser

-

Am J Ophthalmol, 98 (1984), pp. 807–808

-

|

|

|

-

- 19

- A.J. Dickinson, R.E. Gaucas

-

Orbital lymphatics: do they exist?

-

Eye, 20 (2006), pp. 1145–1148

-

|

|

-

- 20

- S. Duke-Elder

-

Diseases of the outer eye: conjunctiva

-

S. Duke-Elder (Ed.), System of Ophthalmology, Vol. 8, Part 1, Mosby, St Louis, MO (1965), p. 40

-

- 21

- N. Efron, M. Al-Dossari, N. Prichard

-

In vivo confocal microscopy of the bulbar conjunctiva

-

Clin Exp Ophthalmol, 37 (2009), pp. 335–344

-

|

|

-

- 22

- J. Eisenhoffer, A. Kagal, T. Klein

-

Importance of valves andlymphangion contractions in determining pressure gradients in isolated lymphatics exposed to elevations in outflow pressure

-

Microvasc Res, 49 (1995), pp. 97–110

-

|

|

|

-

- 23

- Y.R. Enzer, N. Shorr

-

Medical and surgical management of chemosis after blepharoplasty

-

Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg, 10 (1994), pp. 57–63

-

|

|

-

- 24

- B. Esmaeli, X. Wang, A. Youssef, et al.

-

Patterns of regional and distant metastasis in patients with conjunctival melanoma: experience at a cancer center over four decades

-

Ophthalmology, 108 (2001), pp. 2101–2105

-

|

|

|

-

- 25

- A.K. Farr, B. Shalev, T.O. Crawford, et al.

-

Ocular manifestations of Ataxia-telangectasia

-

Am J Ophthalmol, 134 (2002), pp. 891–896

-

|

|

|

-

- 26

- R. Folberg, F.A. Jakobiec, V.B. Bernardino, et al.

-

Benign conjunctival melanocytic lesions: clinicopathological features

-

Ophthalmology, 96 (1989), pp. 436–461

-

|

|

|

-

- 27

- F.W. Fraunfelder

-

Liquid nitrogen cryotherapy for conjunctival lymphangiectasia: a case series

-

Arch Ophthalmol, 127 (2009), pp. 1686–1687

-

|

-

- 28

- F.W. Fraunfelder

-

Liquid nitrogen cryotherapy for conjunctival lymphangiectasia: a case series

-

Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc, 107 (2009), pp. 229–232

-

|

-

- 29

- M. Fukunaga

-

Expression of D2-40 in lymphatic endothelium of normal tissues and in vascular tumours

-

Histopathology, 46 (2005), pp. 396–402

-

|

|

-

- 30

- R.E. Gausas, R.S. Gonnering, B.N. Lemke, et al.

-

Identification of human orbital lymphatics

-

Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg, 15 (1999), pp. 252–259

-

|

|

-

- 31

- D. Granet

-

Allergic rhinoconjunctivitis and differential diagnosis of the red eye

-

Allergy Asthma Proc, 29 (2008), pp. 565–574

-

|

|

-

- 32

- H.E. Grossniklaus, W.R. Green, M. Luckenbach, et al.

-

Conjunctival lesions in adults. A clinical and histopathologic review

-

Cornea, 6 (1987), pp. 78–116

-

|

|

-

- 33

- K. Gündüz, S. Demirel, B. Yagmurlu, et al.

-

Correlation of surgical outcome with neuroimaging findings in periocular lymphaniomas

-

Ophthalmology, 113 (2006), pp. 1231.e1–1231.e8

-

|

-

- 34

- G.J. Harris

-

Orbital vascular malformations: a consensus statement on terminology and its clinical implications. Orbital Society

-

Am J Ophthalmol, 127 (1999), pp. 453–455

-

|

-

- 35

- G.J. Harris, P.J. Sakol, G. Bonavolonta, et al.

-

An analysis of thirty cases of orbital lymphangioma: pathophysiologic considerations and management recommendations

-

Ophthalmology, 97 (1990), pp. 1583–1592

-

|

|

|

-

- 36

- G.J. Harris, K.I. Woo, C.J. Schultz, et al.

-

Late-onset chemosis in patients with head and neck tumors

-

Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg, 20 (2004), pp. 436–441

-

|

|

-

- 37

- M.J. Hawes, R.K. Dortzbach

-

The microscopic anatomy of the lower eyelid retractors

-

Arch Ophthalmol, 100 (1982), pp. 1313–1318

-

|

-

- 38

- A.S. Hawkins, N.A. Hamming

-

Thermal cautery as a treatment for conjunctival inclusion cyst after strabismus surgery

-

J AAPOS, 5 (2001), pp. 48–49

-

|

|

|

-

- 39

- L.M. Heindl, T.N. Hofmann, F. Schrödl, et al.

-

Intraocular lymphatics in ciliary body melanomas with extraocular extension: functional for lymphatic spread?

-

Arch Ophthalmol, 128 (2010), pp. 1001–1008

-

|

|

-

- 40

- A. Irrthum, M.J. Karkkainen, K. Devriendt, et al.

-

Congenital hereditary lymphedema caused by a mutation that inactivates VEGFR3 tyrosine kinase

-

Am J Hum Genet, 67 (2000), pp. 295–301

-

|

|

|

|

-

- 41

- F.A. Jakobiec, P.A. Bonnaro, J. Sigelman

-

Conjunctival adnexal cysts and dermoids

-

Arch Ophthalmol, 96 (1978), pp. 1404–1409

-

|

-

- 42

- B. Jay

-

Naevi and melanomata of the conjunctiva

-

Br J Ophthalmol, 49 (1965), pp. 169–204

-

|

|

-

- 43

- I.S. Jones

-

Lymphangiomas of the ocular adnexa: an analysis of 62 cases

-

Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc, 57 (1959), pp. 602–665

-

|

-

- 44

- D.R. Jordan, R.L. Anderson

-

Carbon dioxide (CO2) laser therapy for conjunctival lymphangioma

-

Ophthalmic Surg, 18 (1987), pp. 728–730

-

|

-

- 45

- N. Kafil-Hussain, R. Khooshabeh, C. Graham

-

Superficial adnexal lymphangioma

-

Orbit, 24 (2005), pp. 141–143

-

|

|

-

- 46

- H.J. Kahn, D. Bailey, A. Marks

-

Monoclonal antibody D2-40, a new marker of lymphatic endothelium, reacts with Kaposi’s sarcoma and a subset of angiosarcomas

-

Mod Pathol, 15 (2002), pp. 434–440

-

|

|

-

- 47

- N.S. Kalin, S.E. Orlin, A.E. Wulc, et al.

-

Chronic localised conjunctival chemosis

-

Cornea, 15 (1996), pp. 295–300

-

|

|

-

- 48

- T.V. Karlsen, M.J. Kakkainen, K. Alitato, et al.

-

Transcapillary fluid balance consequences of missing initial lymphatics studied in a mouse model of primary lymphedema

-

J Physiol, 574 (2006), pp. 583–596

-

|

|

-

- 49

- T. Karpanen, T. Makinen

-

Regulation of lymphangiogenesis—from cell fate determination to vessel remodelling

-

Exp Cell Res, 312 (2006), pp. 575–583

-

|

|

|

-

- 50

- S.E. Katz, J.M. Rootman, S. Vangveeravong, et al.

-

Combined venous lymphatic malformations of the orbit (so-called lymphangiomas). Association with non-contiguous intracranial vascular anomalies

-

Ophthalmology, 105 (1998), pp. 176–184

-

|

|

|

-

- 51

- D. Kerjaschki

-

The crucial role of macrophages in lymphangiogenesis

-

J Clin Invest Sci, 115 (2005), pp. 2316–2319

-

|

-

- 52

- H. Kiratli, S. Bilgic, O. Gokoz, et al.

-

Conjunctival epithelial inclusion cyst arising from a pterygium

-

Br J Ophthalmol, 80 (1996), pp. 769–770

-

|

|

-

- 53

- A. Kobayashi, K. Sugiyama

-

Visualization of conjunctival cyst using Healon V and Trypan blue

-

Cornea, 24 (2005), pp. 759–760

-

|

-

- 54

- I. Kyprianou, M. Nessim, V. Kumar, et al.

-

A case of lymphangiectasia haemorrhagica conjunctivae following phacoemulsification

-

Acta Ophthalmol Scand, 82 (2004), pp. 627–628

-

|

|

-

- 55

- T. Leber

-

Lymphangiectasia haemorrhagica conjunctivae

-

Graefes Arch Ophthalmol, 26 (1880), pp. 197–201

-

|

-

- 56

- S.W. Lee, S.C. Lee, K.H. Jin

-

Conjunctival inclusion cysts in longstanding chronic vernal conjunctivitis

-

Korean J Ophthalmol, 21 (2007), pp. 251–254

-

|

-

- 57

- L.J. Leffertstra

-

Lymphangiectasia hemorrhagica conjunctivae

-

Ophthalmologica, 143 (1962), pp. 133–136

-

- 58

- M.R. Levine, R. Davies, J. Ross

-

Chemosis following blepharoplasty: an unusual complication

-

Ophthalmic Surg, 25 (1994), pp. 593–596

-

|

-

- 59

- S.E. Liyanage, G.M.T. Watson, M.J. Wearne

-

Late ocular manifestation of a childhood venous-lymphatic malformation

-

Eye, 22 (2007), pp. 1194–1195

-

- 60

- J. Lochhead, L. Benjamin

-

Lymphangiectasia haemorrhagica conjunctivae

-

Eye, 12 (1998), pp. 627–629

-

|

-

- 61

- D. Lui

-

Conjunctivochalasis: a cause of tearing and its management

-

Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg, 2 (1986), pp. 25–28

-

- 62

- T.J. Malone, D.T. Tse

-

Surgical treatment of chemotic conjunctival prolapse following vitreoretinal surgery

-

Arch Ophthalmol, 108 (1990), pp. 890–891

-

|

|

-

- 63

- F. Mantelli, A. Lambiase, S. Bonini

-

A simple and rapid diagnostic algorithim for the detection of ocular allergic diseases

-

Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol, 9 (2009), pp. 471–476

-

|

|

-

- 64

- M. Mehta, M. Waner, A. Fay

-

Amniotic membrane grafting in the management of conjunctival vascular malformations

-

Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg, 25 (2009), pp. 317–375

-

- 65

- D.M. Meisler, R.A. Eiferman, N.B. Ratliff, et al.

-

Surgical management of conjunctival lymphangiectasia by conjunctival resection

-

Am J Ophthalmol, 136 (2003), pp. 735–736

-

|

|

|

-

- 66

- D. Meller, S.C. Tseng

-

Conjunctivochalasis: literature review and possible pathophysiology

-

Surv Ophthalmol, 43 (1998), pp. 225–232

-

|

|

|

-

- 67

- E.M. Messmer, M.J. Mackert, D.M. Zapp, et al.

-

In vivo confocal microscopy of normal conjunctiva and conjunctivitis

-

Cornea, 25 (2006), pp. 781–788

-

|

|

-

- 68

- S. Morax, V. Touitou

-

Complications of blepharoplasty

-

Orbit, 25 (2006), pp. 303–318

-

|

|

-

- 69

- A. Moriondo, A.S. Mukenge, D. Negrini

-

Transmural pressure in rat initial subpleural lymphatics during spontaneous or mechanical ventilation

-

Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol, 289 (2005), pp. H263–H269

-

|

|

-

- 70

- S. Narayanappa, Dayananda, M. Dakshayini, et al.

-

Conjunctival inclusion cysts following small incision cataract surgery

-

Indian J Ophthalmol, 58 (2010), pp. 423–425

-

|

-

- 71

- S. Nicholas, A. Wells

-

Subconjunctival hemorrhage and conjunctivochalasis

-

Ophthalmology, 117 (2010), pp. 1276–1277

-

|

|

|

-

- 72

- N. Nijhawan, M.I. Ross, R. Diba, et al.

-

Experience with sentinel lymph node biopsy for eyelid and conjunctival malignancies at a cancer center

-

Ophth Plast Reconstr Surg, 20 (2004), pp. 291–295

-

|

|

-

- 73

- S.J. Ono, M.B. Abelson

-

Allergic conjunctivitis: update on pathophysiology and prospects for future treatment

-

J Allergy Clin Immunol, 115 (2005), pp. 118–122

-

|

|

|

-

- 74

- I. Otaka, N. Kyu

-

A new surgical technique for management of conjunctivochalasis

-

Am J Ophthalmol, 129 (2000), pp. 385–387

-

|

|

|

-

- 75

- H.D. Perry, A.J. Cossari

-

Chronic lymphangectasis in Turner’s syndrome

-

Br J Ophthalmol, 70 (1986), pp. 396–399

-

|

|

-

- 76

- P. Prabhasawat

-

Preserved amniotic membrane transplantation for conjunctival surface reconstruction

-

Cell Tissue Bank, 2 (2001), pp. 31–39

-

|

|

-

- 77

- R. Riise, J. Ygge, C. Lindman, et al.

-

Ocular findings in Norwegian patients with ataxia–telangectasia: a 5 year prospective cohort study

-

Acta Ophthalmol Scand, 85 (2007), pp. 557–562

-

|

|

-

- 78

- J. Rootman, E. Hay, D. Graeb, et al.

-

Orbital-adnexal lymphangiomas. A spectrum of hemodynamically isolated vascular hamartomas

-

Ophthalmology, 93 (1986), pp. 1558–1570

-

|

|

|

-

- 79

- S.I. Rosenfeld, M.E. Smith

-

Benign cystic nevus of the conjunctiva

-

Ophthalmology, 90 (1983), pp. 1459–1461

-

|

|

|

-

- 80

- K. Savitsky, A. Bar-Shira, S. Gilad, et al.

-

A single ataxia telangectasia gene with a product similar to PI-3 kinase

-

Science, 286 (1995), pp. 1749–1753

-

|

-

- 81

- K.R. Scott, D.T. Tse, J.W. Kronish

-

Hemorrhagic lymphangiectasia of the conjunctiva

-

Arch Ophthalmol, 109 (1991), pp. 286–287

-

|

|

-

- 82

- D.D. Sherman, R.S. Gonnering, I.H.L. Wallow, et al.

-

Identification of orbital lymphatics: enzyme histochemical light microscopic and electron microscopic studies

-

Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg, 9 (1993), pp. 153–169

-

|

|

-

- 83

- J.A. Shields, R.C. Eagle, R.E. Gausas, et al.

-

Retrograde metastasis of cutaneous melanoma to conjunctival lymphatics

-

Arch Ophthalmol, 127 (2009), pp. 1222–1223

-

- 84

- J.A. Shields, C.L. Shields

-

Tumors of the conjunctiva and cornea

-

G. Smolin, R.A. Thoft (Eds.), The Cornea: Scientific Foundations and Clinical Practice (ed 3), Little Brown, Boston (1994), pp. 586–595

-

- 85

- J.A. Shields, C.L. Shields

-

Conjunctival lymphangiectasia and lymphangioma

-

J.A. Shields, C.L. Shields (Eds.), Eyelid, Conjunctival, and Orbital Tumors: An Atlas and Textbook, Lippincourt Williams and Wilkins, Philadelphia (2007) pp 354–5

-

- 86

- C.L. Shields, A. Fasiudden, A. Mashayekhi, et al.

-

Conjunctival nevi

-

Arch Ophthalmol, 122 (2004), pp. 167–175

-

|

|

-

- 87

- C.L. Shields, J.A. Shields

-

Tumors of the conjunctiva and cornea

-

Surv Ophthalmol, 49 (2004), pp. 3–24

-

|

|

|

-

- 88

- C.L. Shields, J.A. Shields

-

Conjunctival tumors in children

-

Curr Opin Ophthalmol, 18 (2007), pp. 351–360

-

|

|

-

- 89

- D. Singh, R.S.J. Singh, K. Singh, et al.

-

The conjunctival lymphatic system

-

Ann Ophthalmol, 35 (2003), pp. 99–104

-

|

-

- 90

- J.J. Song, P.T. Finger, M. Kurli, et al.

-

Giant secondary conjunctival inclusion cysts a late complication of strabismus surgery

-

Ophthalmology, 113 (2006), pp. 1045–1049

-

|

-

- 91

- J.A. Spector, B.M. Zide

-

Carbon dioxide laser ablation for the treatment of lymphangioma of the conjunctiva

-

Plast Reconstr Surg, 117 (2006), pp. 609–612

-

|

|

-

- 92

- C.W. Spraul, H.J. Buchwald, G.K. Lang

-

Idiopathic conjunctival lymphangiectasia

-

Klin Monbl Augenheilkd, 210 (1997), pp. 398–399

-

|

|

-

- 93

- H.S. Sugar, A. Riazi, R. Schaffner

-

The bulbar conjunctival lymphatics and their clinical significance

-

Tran Am Acad Ophthalmol Otolaryngol, 61 (1957), pp. 212–223

-

|

-

- 94

- A. Swift, D. Morrell, E. Cromartie, et al.

-

The incidence and gene frequency of ataxia-telangectasia in the United States

-

Am J Hum Genet, 39 (1986), pp. 573–582

-

- 95

- A. Szuba, M. Skobe, M.J. Karkkainen, et al.

-

Therapeutic lymphangiogenesis with human recombinant VEGF-C

-

FASEB J, 16 (2002), pp. 1985–1987

-

|

-

- 96

- M. Tunç, E. Sadri, D.H. Char

-

Orbital lymphangioma: an analysis of 26 patients

-

Br J Ophthalmol, 83 (1999), pp. 76–80

-

|

|

-

- 97

- M.R. Vishwanath, A. Jain

-

Conjunctival inclusion cyst following sub-Tenon’s local anaesthetic injection

-

Br J Anaesth, 95 (2005), pp. 825–826

-

|

|

-

- 98

- A. Watanabe, N. Yokoi, S. Kinoshita, et al.

-

Clinicopathologic study of conjunctivochalasis

-

Cornea, 23 (2004), pp. 294–298

-

|

|

-

- 99

- B.J. Williams, F.J. Durcan, N. Mamalis

-

Conjunctival epithelial inclusion cyst

-

Arch Ophthalmol, 115 (1997), pp. 816–817

-

|

|

-

- 100

- J.E. Wright, T.J. Sullivan, A. Garner, et al.

-

Orbital venous anomalies

-

Ophthalmology, 104 (1997), pp. 905–913

-

|

|

|

-

- 101

- C. Yong, E.A. Bridenbaugh, D.C. Zawieja, et al.

-

Microarray analysis of VEGF-C responsive genes in human lymphatic endothelial cells

-

Lymphat Res Biol, 3 (2005), pp. 183–207

-

|

|

-

- 102

- D.Y. Yu, W.H. Morgan, X. Sun, et al.

-

The critical role of the conjunctiva in glaucoma filtration surgery

-

Prog Retin Eye Res, 28 (2009), pp. 303–328

-

|

|

|

-

- 103

- E. Zamir, H. Mechoulam, A. Micera, et al.

-

Inflamed juvenile conjunctival naevus: clinicopathological characterisation

-

Br J Ophthalmol, 86 (2002), pp. 28–30

-

|

|

-

- 104

- P. Zimmerman, T. Dietrich, F. Bock, et al.

-

Tumour-associated lymphangiogensis in conjunctival malignant melanoma

-

Br J Ophthalmol, 93 (2009), pp. 1529–1534

More info below:

From: http://webeye.ophth.uiowa.edu/eyeforum/atlas/pages/conjunctival-lymphangiectasis.htm

EyeRounds Online Atlas of Ophthalmology

Conjunctival lymphangiectasis

Contributor: Christopher A Kirkpatrick, MD

Photographer, Cindy Montague, CRA

Category(ies): Cornea; External Eye Disease

Conjunctival lymphangiectasis is a condition in which conjunctival swelling occurs as a result of dilated conjunctival lymphatic channels, most notably on the bulbar conjunctiva. The appearance at the slit lamp will show cystic appearing clear or yellowish, elevated conjunctival lymphatic channel(s) separated by translucent septate walls. Although the actual cause is unknown, the presumed underlying etiology is obstructed lymphatic channels. The condition is thought of as benign, but can be associated with local inflammation, disruption of the tear film/dellen, or secondary hemorrhage (hemorrhagic lymphangiectasia of the conjunctiva).

The above pictures show this condition in a young, asymptomatic patient. Included is an anterior segment OCT centered over the area of interest.

ABSTRACT The authors report the case of a 41-year-old woman presenting with both intermittent conjunctival swelling and dilated conjunctival vessels on ocular examination in the right eye who was diagnosed as having conjunctival lymphangiectasis. This is a rare disease that occurs as the result of a connection between conjunctival lymphatic and blood vessels.

It is a frustrating condition as it is usually only diagnosed after removing the conjunctiva and sending to pathology.