Herpes Simplex versus Herpes Zoster:

What is the Difference and What is the Treatment for Each

Everyone tends to get confused between the herpes zoster (shingles) and herpes simplex (oral or genital herpes) and often use them interchangeably. The reason why it is so confusing is because they have the basic same name, though they are different viruses and the symptoms can look similar.

A 65 year old patient came in yesterday sent by her dermatologist because she had sores on her nose and upper lip. Most of the sores were just on one side of the nose, but there was one sore that barely crossed the midline. It can be hard to tell if it is HSV1 or HZV=Zoster=Shingles when the rash just starts.

Herpes Simplex Virus, type 1=HSV1=Cold Sores

————————

Herpes Zoster Virus=HZV=Zoster=Shingles

A close friend had her initial symptom be ear pain before the rash started. Luckily we jumped on the Valtrex and she had only a minimal rash unlike the poor lady below.

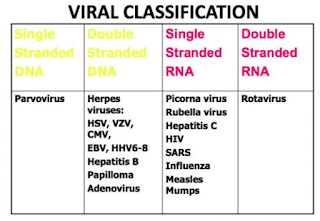

Herpes Viruses come from the same family of Viruses called DNA Viruses: this means they can incorporate into your own DNA, to establish lifelong latent (hidden waiting to be activated) infections and reactivate in immunocompromised conditions.

They include:

2.Herpes simplex virus-2 (HSV-2)=Genital Herpes Virus

3. Herpes Varicella-Zoster virus (VZV): Varicella=Chicken Pox; Zoster=Shingles:

4. Cytomegalovirus (CMV),

5. Epstein–Barr virus (EBV)=Mononucleosis

6. Human herpes virus-6 (HHV-6)

7. Human papilloma viruses (HPV)

Treatment for Each:

For all Herpes infections the mainstay of treatment is essential:

1. Conservative Measures

Wet-to-dry dressings with sterile saline solution or Burow solution (a pharmacologic preparation made of 5% aluminum acetate dissolved in water) should be applied to the affected skin for 30-60 minutes 4-6 times daily. A modified form of Burow solution is commercially sold as Domeboro powder packets, which need to be dissolved in water.

Calamine lotion, a mixture of zinc oxide with about 0.5% iron (III) oxide, may be used as an antipruritic agent. It is also used as a mild antiseptic to prevent infections that can be caused by scratching the affected area, as well as an astringent for weeping or oozing blisters. There is, however, no proof that calamine lotion has any real therapeutic effect on rashes and itching.

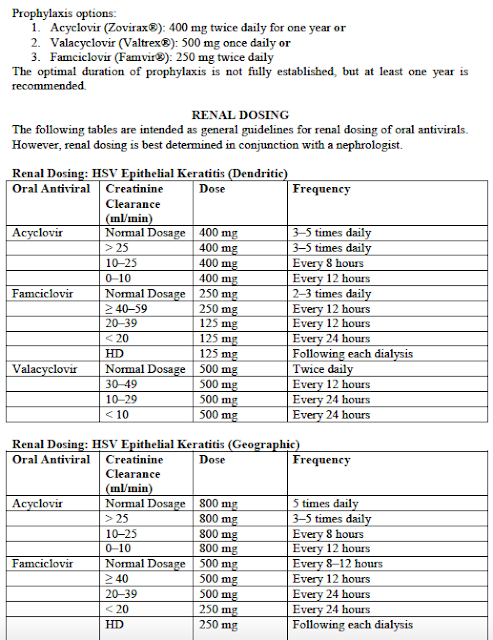

2. Take an Antiviral: decision, unfortunately can depend on which insurance you have & if you are willing to pay for the more expensive versions which require less frequent dosing. Be sure to tell your MD if you have any kidney (renal) issues at all.

3. Get eye check if close to sores close to eye.

4. Prevent side effects with meds.

Specifically:

1. Herpes simplex virus-1 (HSV-1)=Cold Sore Virus;

Rx:

- acyclovir (Zovirax),

- valacyclovir (Valtrex),

- famciclovir (Famvir), and.

- topical acyclovir or penciclovir (Denavir) creams may shorten attacks of recurrent HSV-1 if it is applied early, usually before lesions develop.

- I have used Zirgan in 1 patient whose sores were on the nose & crossed the midline of the nose to see if it would help. It did but it is only a case series of 1 & she was also on Valtrex so I cannot be for sure it was just the Zirgan (see notes on Zirgan below).

2. Herpes simplex virus-2 (HSV-2)=Genital Herpes Virus

three major drugs commonly used to treat genital herpes symptoms: acyclovir (Zovirax), famciclovir (Famvir), and valacyclovir (Valtrex). These are all taken in pill form. Severe cases may be treated with the intravenous (IV) drug acyclovir.

- acyclovir (Zovirax),

- valacyclovir (Valtrex),

- famciclovir (Famvir), and.

3. Herpes Varicella-Zoster virus (VZV): Varicella=Chicken Pox; Zoster=Shingles:

4. Cytomegalovirus (CMV),

5. Epstein–Barr virus (EBV)=Mononucleosis

6. Human herpes virus-6 (HHV-6)

7. Human papilloma viruses (HPV)

Note:

Prevention

Chickenpox can be prevented by vaccination.

Chickenpox can be prevented by vaccination.

Children who have never had chickenpox should get two

doses of chickenpox vaccine, with the 1st dose administered at 12 – 15 months of age and the 2nd at 4-6

years of age.

doses of chickenpox vaccine, with the 1st dose administered at 12 – 15 months of age and the 2nd at 4-6

years of age.

Two doses, administered 4-8 weeks apart, are also recommended for people 13 years of age

or older. There is a safe and effective vaccine to prevent shingles.

or older. There is a safe and effective vaccine to prevent shingles.

It prevents shingles in 50 percent of

those vaccinated and reduces the incidence of PHN by 66 percent. Although people who are vaccinated

may still get shingles, they are likely to experience a milder case than un-vaccinated persons.

those vaccinated and reduces the incidence of PHN by 66 percent. Although people who are vaccinated

may still get shingles, they are likely to experience a milder case than un-vaccinated persons.

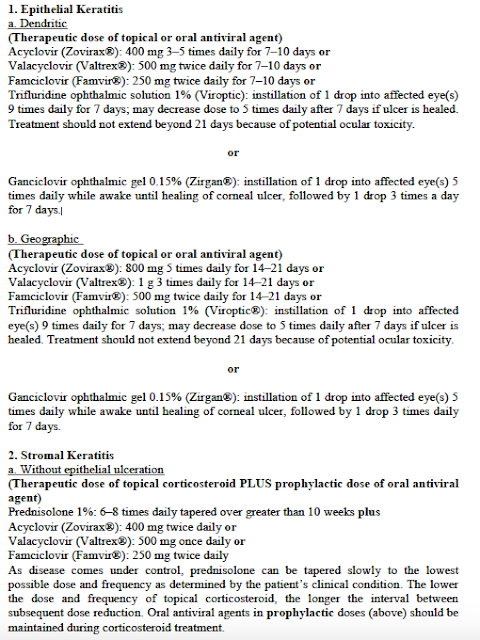

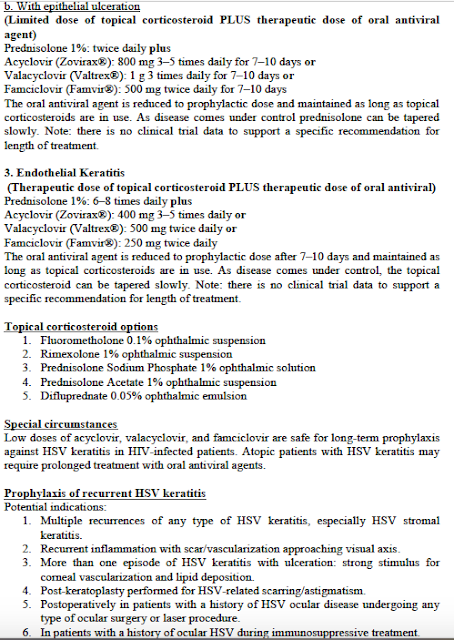

If the Herpes Affects Your Eye: Treatment:

It is a bit more tricky as particular treatment depends on what layers of the eye are affected:

*As demonstrated in a phase 3 open-label, randomized, controlled, multicenter clinical trial (N=164) in which patients with herpetic keratitis received either ZIRGAN or acyclovir ophthalmic ointment 3%, administered 5 times daily until healing of ulcer and then 3 times daily for 1 week. Clinical resolution (healed ulcers) at day 7 was achieved in 77% (55/71) of patients treated with ZIRGAN versus 72% (48/67) treated with acyclovir (difference, 5.8%; 95% CI, -9.6%-18.3%). ZIRGAN was noninferior to acyclovir in patients with dendritic ulcers.

See below for Indication and Important Safety Information.

INDICATION

ZIRGAN (ganciclovir ophthalmic gel) 0.15% is a topical ophthalmic antiviral that is indicated for the treatment of acute herpetic keratitis (dendritic ulcers).

IMPORTANT SAFETY INFORMATION

-

ZIRGAN is indicated for topical ophthalmic use only.

-

Patients should not wear contact lenses if they have signs or symptoms of herpetic keratitis or during the course of therapy with ZIRGAN.

-

Most common adverse reactions reported in patients were blurred vision (60%), eye irritation (20%), punctate keratitis (5%), and conjunctival hyperemia (5%).

-

Safety and efficacy in pediatric patients below the age of 2 years have not been established.

Click here for Prescribing Information about ZIRGAN.

References: 1. Foster CS. Ganciclovir gel—a new topical treatment for herpetic keratitis. US Ophthalmic Rev. 2008;3(1):52-56. 2. ZIRGAN Prescribing Information, April 2014. 3. Croxtall JD. Ganciclovir ophthalmic gel 0.15% in acute herpetic keratitis (dendritic ulcers). Drugs. 2011;71(5):603-610.

Here is more information:

Is Shingles a Form of Herpes?

Yes but there are eight types of Herpes Human Virus (HHV) all of which has an effect on humans.

They include:

They include:

- HHV1: Also known as Herpes Simplex Virus 1 (HSV -1) and it causes oral herpes also known as cold sores.

- HHV2: Also known as Herpes Simplex Virus 2 (HSV – 2) and it causes genital herpes.

- HHV3: Also known as Varicella Zoster Virus (VZV) and it causes chickenpox when people are infected with it for the first time. The symptoms can recur as shingles later on in life!

- HHV4: Also known as Ebstein Barr Virus (EBV) and it causes mononucleosis in humans. In popular jargon this disease is also known as glandular fever or simply as mono.

- HHV5: Also known as Cytomegolo Virus (CMV) and it effect 5 out of every 1000 live births. Children infected with this virus initially show symptoms that are very similar to rubella.

- HHV6: Also known as Roseolovirus because it causes Roseola Infantum, which is essentially a high fever accompanied by a rash.

- HHV7: This is very similar to HHV6, however the infections caused by this virus is usually not as severe as that caused by HHV6.

- HHV8: Also known as Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV), which is a form of cancer that people suffering from AIDS are especially susceptible to.

As mentioned above HHV has eight different variants, all of which have multiple sub-variants, a full discussion of which is beyond the scope of this article. So calling shingles a form of herpes would be technically correct, and you may even stretch the definition to say that shingles and herpes are related, however the truth of this claim is only limited to the taxonomy. The symptoms of herpes zoster are different from those of cold sores or genital herpes, the key differences of which can be deciphered if we compare them side by side.

Difference Between Shingles and Oral or Genital Herpes:

Shingles=Zoster affects skin dermatomes. Oral Herpes is due to HSV 1 most often. Genital Herpes is due to HSV 2 and affects genital areas.

Treatment for Shingles and Oral or Genital herpes:

People can at times be forgiven for thinking that shingles and herpes are the same if they have ever seen the prescription or the recovery methods, because they are almost carbon copies of each other. Some of the key aspects of the treatment are:

- Taking vitamin supplements that has a significant amount of Vitamin C and Zinc provides a necessary boost to our natural immunity and prevents the onset of herpes zoster or a recurrence of herpes simplex.

- People are usually suggested to try “over the counter” medication like ibuprofen or paracetamol to help ease the pain. Topical application of Vaseline or a similar petroleum jelly or even Aloe Vera is also highly recommended. However herpes zoster tends to be a lot more painful than herpes simplex, hence some advanced pain medication for people suffering from shingles may be required. To help ease the pain, an application of lidocaine may be prescribed. In extreme cases, prescription of opiates such as Hydrocodone (Brand Name: Vicodin) and Oxycodone (Brand Names: Oxycontin, Percocet, Percodan) is not unheard of!

- A warm bath provides patients of shingles, cold sores or genital herpes with temporary relief.

- For both herpes zoster and herpes simplex, strong anti-viral medication is prescribed. Some example are Famciclovir (Brand Name: Famvir), Valacyclovir (Brand Name: Valtrex) and Acyclovir (Brand Name: Zovirax).

- If the blisters or lesions get ruptured, then it leaves the patients of both shingles and herpes vulnerable to secondary infection. To counter that, flucloxacillin or erythromycin may also be prescribed.

Prevention is the best form of cure hence building up and maintaining a healthy immune system, maintaining proper hygiene and refraining from risky sexual behavior can go a long way towards preventing an outbreak!

What Causes Herpes Infections and Outbreaks?

Herpes simplex type 1, which is transmitted through:

1. Any oral secretions or sores on the skin,

2. Kissing

3. Sharing a toothbrushes or eating utensils.

1. Any oral secretions or sores on the skin,

2. Kissing

3. Sharing a toothbrushes or eating utensils.

Most often, a person can only get herpes type 2 infection during sexual contact with someone who has a genital HSV-2 infection. It is important to know that both HSV-1 and HSV-2 can be spread even if sores are not present.

Pregnant women with genital herpes should talk to their doctor, as genital herpes can be passed on to the baby during childbirth.

For many people with the herpes virus, which can go through periods of being dormant (=asleep=latent).

Attacks (or outbreaks) can be brought on by the following conditions:

- Stress: physical or mental

- General illness (from mild illnesses to serious conditions)

- Fatigue

- Physical or emotional stress

- Immunosuppression due to AIDS or such medications as chemotherapy or steroids

- Trauma to the affected area, including sexual activity

- Menstruation

What Are the Symptoms of Herpes Simplex?

Symptoms of herpes simplex virus typically appear as a blister or as multiple blisters on or around affected areas on both sides of the body– usually the mouth, genitals, or rectum. The blisters break, leaving tender sores. If the sores are only on one side of the body, be checked to be sure it is not Herpes Zoster or Shingles which is a different virus altogether and is due to the reactivation of the Chicken Pox Varicella virus you got when you were young.

How Is Herpes Simplex Diagnosed?

Often, the appearance of herpes simplex virus is typical and no testing is needed to confirm the diagnosis. If a health care provider is uncertain, herpes simplex can be diagnosed with lab tests, including DNA — or PCR — tests and virus cultures.

How Is Herpes Simplex Treated?

Although there is no cure for herpes, treatments can relieve the symptoms. Medication can decrease the pain related to an outbreak and can shorten healing time. They can also decrease the total number of outbreaks. Drugs including Famvir, Zovirax, and Valtrex are among the drugs used to treat the symptoms of herpes. Warm baths may relieve the pain associated with genital sores.

How Painful Is Herpes Simplex?

Some people experience very mild genital herpes symptoms or no symptoms at all. Frequently, people infected with the virus don’t even know they have it. However, when it causes symptoms, it can be described as extremely painful. This is especially true for the first outbreak, which is often the worst. Outbreaks are described as aches or pains in or around the genital area or burning, pain, or difficulty urinating. Some people experience discharge from the vagina or penis.

Oral herpes lesions (cold sores) usually cause tingling and burning just prior to the breakout of the blisters. The blisters themselves can also be painful.

Can Herpes Be Cured?

There is no cure for herpes simplex. Once a person has the virus, it remains in the body. The virus lies inactive in the nerve cells until something triggers it to become active again.

Ocular HSV Treatments

For decades, we used topical trifluridine to treat ocular herpes. Now, we have some new weapons at our disposal.

|

There are eight distinct DNA viruses that infect humans, and five of them cause significant ocular disease. These include: HSV-1, HSV-2, varicella-zoster, cytomegalovirus and Epstein-Barr virus.1

HSV-1, which most commonly affects the eyes, is almost universally acquired. In fact, by age 60, more than 90% of individuals have HSV-1 in their trigeminal ganglia.2 To date, more than 500,000 Americans have been diagnosed with HSV ocular infections, with about 20,000 new cases and 28,000 recurrences reported each year.3

The breakdown is interesting, with 72% of HSV-1 cases involving the epithelium, 41% involving the lids and conjunctiva, 12% the corneal stroma and 9% involving the uveal tract. It’s interesting to note that humans are the only natural reservoir of HSV and that the virus can remain viable for up to two hours on a dry tonometer head or more than eight hours on a wet tonometer tip.4

Here, we review the ophthalmic ramifications of HSV infection as well as discuss some of the latest treatment options.

Primary HSV

- Overview. Typically, HSV-1 infection occurs relatively early in life; however, recent research suggests that primary acquisition of HSV-1 is becoming progressively delayed in industrial countries.2 In most cases, patients with primary HSV exhibit mild flu-like symptoms that may be associated with a low-grade fever. A small percentage of individuals also experience viral skin eruptions, which generally manifest as a vesicular rash found around the eyelids, conjunctiva or facial skin. Often, pre-auricular node swelling and pain also accompany these skin eruptions. After the primary infection runs its course, the HSV becomes latent in the trigeminal ganglion. Recurrent HSV typically occurs in the oral or nasal mucosa because of certain reactivation triggers, such as local trauma from ocular surgery, UV light exposure, hormonal changes, stress and systemic illnesses that compromise the immune system.5

- Treatment. Children who manifest primary HSV usually are less responsive to medications, although they still should be treated with anti-viral medications, such as oral acyclovir or topical antivirals (if a conjunctivitis is present). Topical corticosteroids should be avoided because of the risks associated with further immune system suppression. It is also important to note that laser surgery procedures, such as LASIK and PRK, can reactivate a latent HSV virus.6,7 Additionally, corticosteroids have not been shown to be a trigger for HSV reactivation. Nevertheless, if a reactivation occurs in the presence of steroids, the disease can progress aggressively.8

A Look at Ocular HSV

Corneal involvement of HSV can include epithelial keratitis, neurotrophic keratopathy, stromal keratitis and endotheliitis. The infectious epithelial keratitis presentation includes corneal vesicles, dendritic keratitis and geographic ulcers. Corneal vesicles are the corollary to the vesicular lesions found on the skin or eyelids. They are cystic or small, raised, clear lesions that contain the active virus. Corneal dyes are an important diagnostic tool in HSV identification (although epithelial defects will not be apparent at this stage, you will note inverse or negative staining or pooling of the fluoresceine around the raised vesicles). This is a rare clinical presentation because patients typically are not very symptomatic, but as the vesicles coalesce, they form the classic dendritic ulcer presentation.

Corneal involvement of HSV can include epithelial keratitis, neurotrophic keratopathy, stromal keratitis and endotheliitis. The infectious epithelial keratitis presentation includes corneal vesicles, dendritic keratitis and geographic ulcers. Corneal vesicles are the corollary to the vesicular lesions found on the skin or eyelids. They are cystic or small, raised, clear lesions that contain the active virus. Corneal dyes are an important diagnostic tool in HSV identification (although epithelial defects will not be apparent at this stage, you will note inverse or negative staining or pooling of the fluoresceine around the raised vesicles). This is a rare clinical presentation because patients typically are not very symptomatic, but as the vesicles coalesce, they form the classic dendritic ulcer presentation.

|

| New treatments for ocular herpes could potentially benefit this patient who presented with significant iritis secondary to HSV. |

The dendritic ulcer is the most common presentation of ocular HSV. The features include a branching lesion with swollen epithelial borders. It is sometimes difficult to differentiate a pseudodendrite (i.e., as seen in herpes zoster) from HSV. The key is to realize that HSV dendrites are true ulcers, so they accrue stain within the lesion as well as along the borders and terminal end bulbs. This can often be enhanced with the addition of lissamine or rose bengal dye.

The geographic ulcer is essentially an enlarged or expanding dendritic ulcer that often presents with scalloped borders. The geographic ulcer can occur if a patient with a dendritic ulcer is placed on a corticosteroid. Other forms of HSV keratitis include the marginal ulcer. This lesion mimics a Staphylococcal hypersensitivity or sterile infiltrative keratitis as a lesion near the limbus. Because the location is in close proximity to the blood vessels, it causes rapid infiltration of white blood cells under the ulcered area. Patients with HSV marginal ulcers are more symptomatic than patients with sterile limbal infiltrates. Additionally, HSV marginal ulcers do not exhibit a clear zone between the infiltrate and the limbus, and they show the presence of deep stromal vessels.

Research shows that 10% of patients with epithelial keratitis go on to experience stromal disease within one year.9 Stromal forms of keratitis include neurotrophic keratopathy, immune stromal keratitis (ISK) or interstitial keratitis and endotheliitis. Stromal haze and neovascularization (also known as ghost vessels) with an intact epithelium are the hallmark signs of ISK. Occasionally, it can present as an immune ring. This presentation is most common in recurrent HSV disease and may often be accompanied by cell and flare in the anterior chamber.

Finally, disciform endotheliitis presents with a deep disc-shaped area of edema and keratic precipitates on the endothelium but no stromal infiltrate or neovascularization. Typically, endotheliitis has a corresponding mild to moderate iritis and is often associated with elevated IOP.

New Treatment Options

During the last decade, there has been a trend toward the use of oral antivirals for the treatment of all forms of HSV. This shift was due, in part, to higher rates of corneal toxicity that were associated with the topical antiviral medications that were available 10 years ago. It is interesting to note that trifluridine was approved in the U.S. more than 30 years ago, and only last year did we see the introduction of a new topical antiviral––Zirgan (0.15% ganciclovir gel, Bausch + Lomb).

During the last decade, there has been a trend toward the use of oral antivirals for the treatment of all forms of HSV. This shift was due, in part, to higher rates of corneal toxicity that were associated with the topical antiviral medications that were available 10 years ago. It is interesting to note that trifluridine was approved in the U.S. more than 30 years ago, and only last year did we see the introduction of a new topical antiviral––Zirgan (0.15% ganciclovir gel, Bausch + Lomb).

- Zirgan. This prodrug is only activated by the viral enzyme thymidine kinase to inhibit synthesis of viral DNA. Because of this, Zirgan is more selective than other antiviral agents and does not target healthy corneal cells. Zirgan should be dosed five times a day until the dendritic ulcer is healed, and then three times a day for an additional seven days. It does not require refrigeration and unlike Viroptic (trifluridine, Monarch Pharmaceuticals), Zirgan is preserved with 0.075mg of BAK. It also has a comparable pH and osmolarity to natural tears.

- Valtrex. Another development in the improved management of HSV is the increased availability of oral Valtrex (valacyclovir, GlaxoSmithKline), which became available as a generic medication in November 2009. Although all oral antivirals demonstrate low toxicity and are very effective, valacyclovir has five times the bioavailability of acyclovir.10

Still, with the approval of Zirgan and its selective antiviral properties and lessening of epithelial toxicity, we may again see clinicians switching back to topical medications for managing HSV keratitis and limiting systemic drug exposure.

New developments in HSV keratitis treatments have prompted clinicians to stay abreast of the most effective management strategies of this multi-presentation virus. Understanding the various forms of HSV keratitis can aid in accurate diagnosis and successful treatment, thus reducing the risk for associated corneal morbidity.

For Herpes Zoster or Shingles:

Below modified from: http://www.webmd.com/drugs/2/drug-4085/famvir-oral/details

If you had chickenpox as a kid, it is not over yet! 1 million American adults each year get chicken pox like rash all over again, but this time it returns and can be very painful: it is called shingles. And if not treated properly it can cause a lifetime of pain called Post Herpetic Neuralgia.

The great news is we have better ways to prevent PHN in most patients.

The pain of shingles can be excruciating, but the condition goes away in a few weeks — for most people. Postherpetic neuralgia (PHN), a form of neuropathic pain that can last for months or years, even after the virus is no longer active.

Postherpetic neuralgia can make you feel truly miserable.

Chickenpox, shingles, and postherpetic neuralgia all result from infection with a single virus called varicella zoster virus (VZV). Most people catch the varicella zoster virus as children, itch and shiver through the rash and fever of chickenpox, and get better.

But that’s not necessarily the end of the story of varicella infection. After a bout of chickenpox, our immune systems never completely eradicate the VZV virus. They just chase it into hiding. Varicella retreats into nerve cells deep under the skin, near the spine.

For most of us, VZV lies dormant inside our bodies throughout our lives, never causing further problems. In about one-third of people, however, VZV infection has a second act. The virus emerges from hiding, travels along a nerve to the skin, and erupts in a bumpy, painful rash on one side of the body. This sneak attack is called herpes zoster, or shingles. (Varicella zoster virus belongs to the family of herpes viruses, but does not cause cold sores or genital herpes.)

Shingles Symptoms: What Should You Look For?

Unlike the whole-body rash of chickenpox, the shingles rash is limited to the area of skin assigned to the infected nerve. The rash usually consists of small bumps that may turn into blisters before bursting and crusting over. If shingles appears on the face, the eye can be affected, posing a threat to sight.

Also unlike chickenpox, this rash hurts, sometimes intensely. People typically describe shingles pain as burning, stabbing, or electrical.

“Shingles can be almost unbearably painful,” says Jeffrey Ralph, MD, assistant professor of neurology at the University of California in San Francisco and a fellow of the Neuropathy Association. “The nerve itself is inflamed. The pain can sometimes come even weeks before a rash appears.”

When Shingles Becomes Painful Postherpetic Neuralgia

In 10% to 20% of these people, however, the pain of shingles keeps hanging on after the rash is gone. “These folks go on to get postherpetic neuralgia, and we’re not exactly sure why,” Ralph tells WebMD. “Either the pain of shingles never leaves, or it resolves, comes back, and never goes away completely.”

PHN typically occurs in the area where the shingles occurred. The pain can be intermittent or constant, and it can take on any of the diverse qualities of shingles pain. Normal touching of the skin can set it off, Ralph adds. This is called allodynia.

The pain of postherpetic neuralgia can interfere with daily activities, exercise, sleep, and sexual desire. Irritability and depression often follow. “Generally, it makes people feel terrible if it can’t be controlled,” Rumbaugh says.

Why the pain of postherpetic neuralgia persists has mystified researchers. It’s not due to ongoing infection by VZV, but is thought to be due to residual damage or inflammation in the nerve after shingles resolves. It’s also impossible to predict who’ll get shingles or postherpetic neuralgia, although age, race, and health seem to have some impact.

Shingles and Postherpetic Neuralgia: What Are the Risk Factors?

You can’t control whether you’ll catch the chickenpox virus. Fully 99.5% of adults in the U.S. carry it, whether or not they remember having had chickenpox. But why do one-third of those people get shingles — and some of them go on to develop postherpetic neuralgia?

The risk of postherpetic neuralgia also goes up with age. More than 80% of cases of postherpetic neuralgia occur in people over 50 years old. “It’s likely that the natural decline of immunity with age is responsible,” says Ralph.

The results of one study showed that age had a huge effect on the risk for postherpetic neuralgia after shingles:

- Among people under 60 years old who had shingles, less than one in 50 developed postherpetic neuralgia.

- In people aged 60 to 69, about 7% of shingles sufferers developed postherpetic neuralgia.

- In those age 70 and older, almost 20% developed postherpetic neuralgia after a bout of shingles.

Race seems to matter, too. For unknown reasons, white Americans get shingles and postherpetic neuralgia at more than twice the rate of African-Americans in their age group.

“People whose immune systems are impaired by drugs or diseases like AIDS are also more prone to zoster and PHN,” adds Ralph.

Exposure to someone with chickenpox or shingles does not increase your personal risk, however. In fact, experts believe that the slight immune stimulation may boost natural defenses, making you less likely to develop shingles or PHN.

Vaccine Prevention for Shingles and Postherpetic Neuralgia

In 2006, a vaccine to prevent shingles came onto the market. Called Zostavax, the vaccine cuts the likelihood of getting shingles after chickenpox by about half, dramatically reducing the number of people who might get nerve pain after shingles.

Based on these results, the CDC recommends Zostavax to all adults age 60 and older. Rumbaugh goes further: He suggests you get vaccinated at any age if you have had shingles. His clinical experience suggests the vaccine helps reduce postherpetic neuralgia even after infection with the varicella zoster virus.

Early Intervention Is the Key to Treatment

Antiviral medicines such as valacyclovir (Valtrex), famciclovir (Famvir) or acyclovir (Zovirax), taken orally, are usually used to treat shingles. When taken at the very beginning, Ralph says, they can improve symptoms and reduce the risk of postherpetic neuralgia.

Starting antiviral treatment for shingles more than three days after symptoms start is generally believed to be ineffective because the virus is no longer reproducing. Still, many doctors will try treating the condition with antiviral drugs after this time.

HSV-2 Genital Herpes:

Treatment Studies

0.

Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016 Aug 30;(8):CD010684. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD010684.pub2.

Interventions for men and women with their first episode of genital herpes.

Author information

- 1Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, University of Auckland, Private Bag 92019, Auckland, New Zealand, 1023.

Abstract

BACKGROUND:

OBJECTIVES:

SEARCH METHODS:

SELECTION CRITERIA:

DATA COLLECTION AND ANALYSIS:

MAIN RESULTS:

AUTHORS’ CONCLUSIONS:

1.

Clin Drug Investig. 1998;16(3):187-91.

Treatment of genital herpes in males with imiquimod 1% cream: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study.

Author information

- 1Department of Dermatology, University of California San Francisco, San Francisco, California, USA.

Abstract

OBJECTIVE:

PATIENTS:

RESULTS:

CONCLUSION:

Clin Infect Dis. 2006 Feb 15;42(4):575.

Imiquimod 5% cream for the treatment of recurrent, acyclovir-resistant genital herpes.

Comment on

3. Clin Infect Dis. 2006 Feb 15;42(4):575.