How to Do Outcomes Research?

How to Do Outcomes Research in Ophthalmology?

The focus of my research has always been deeply connected with my desire to teach and improve our understanding of how to improve the surgical outcomes of residents and surgeons. Mostly I focused on outcomes research to improve how we teach surgical residents. Thus starting in 2000, my teaching and research contributions at Harvard Medical School focused on the establishment of a database of resident cataract surgery called OASIS (Objective Assessment of Skills in Intraocular Surgery) as part of the Harvard Medical School Residents in Ophthalmology Cataract Surgery outcomes study (HMS ROCS) at the Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary. I started this study in order to improve our surgical outcomes and to identify factors increasing patients’ surgical risk in resident cases. In contrast to other surgical specialties, ophthalmology is severely lacking in published studies on medical education as well as risk analysis in resident cases. Knowledge about how a resident surgeon learns to become competent in their surgical skills and rely less on the surgical preceptor will improve surgical training programs. By mapping out when a surgical preceptor intervenes and when this intervention is no longer needed, we can begin to better understand the learning curve with surgical procedures. This can also apply to seasoned surgeons, if other surgeons are obtaining better results, we need to study why, and see if everyone can get such results. Benchmarks are important to help us all achieve better results for our patients. If I ever need a surgery, I would love to know if my surgeon is above the Benchmark. Currently, the way surgeons do this is by asking the scrub nurses in the OR: “how is he as a surgeon?””does he have a lot of complications.” But this option is not available to everyone, so benchmarks, if done correctly, can protect everyone in the medical and surgical arena.

At Harvard, we created a well organized database, that allowed us to identify some basic factors involved with preoperative surgical evaluation, surgical events, and surgical care that increase a patient’s surgical risk. This database was the first of its kind in any residency program in the United States and since then Harvard Medical School’s Department of Ophthalmology has taken off in doing outcomes research in all aspects of surgery.

Now the rest of the country is starting to see (or be forced) into doing outcomes research.

“Comparative Effectiveness Research” and “Patient Centered Outcomes Research” (PCOR) are the relatively new interchangeable terms that came from legislation leading to the:

Medicare Prescription Drug, Improvement and Modernization Act of 2003, which established the Effective Health Care Program at the Agency for Health Research and Quality (AHRQ); the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 (ARRA) which allocated $1.1 billion for PCOR; and the Affordable Care Act of 2010 which created the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI).

What is PCOR?

PCOR is “The generation and synthesis of evidence that compares the benefits and harms of alternative methods to prevent, diagnose, treat, and monitor a clinical condition or to improve the delivery of care. The purpose of comparative effectiveness research is to assist consumers, clinicians, purchasers, and policy makers to make informed decisions that will improve health.”

[defined by the Institute of Medicine]

Basically this is 360 degrees of evaluation and outcomes research that could be open to insurance, the public and everyone to see.

So it is in every surgeon’s best interest to get moving with their own outcomes research asap before you and your practice are booted from an insurance plan because you fall below the benchmark.

Here is a short cut to doing outcomes research for your busy practice. I have used this to set up outcomes protocols at Harvard and now in private practice at Visionary Eye Doctors, where the owner, Dr. Alberto Martinez, saw immediately the importance of this in 2012 and signed on to hire a full time research assistant.

Here are the steps to launch an effective Outcomes Research Team and Outcomes Research Program

Short Version:

1. Assign an Outcomes Administrator: Find someone on your staff, an MD, OD, RN, or administrator who is passionate about helping patients get the best care in the world at your office. Put this person in charge of the Outcomes Research Program.

You should name the program.

At Harvard, I named our HMS ROCS: Harvard Medical School Residents in Ophthalmology Cataract Surgery outcomes study (HMS ROCS)

At Visionary Eye Doctors, a good title might be: Visionary Eye Doctors Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (VEDPCORI).

or Visionary Eye Doctors Outcomes Research Program (VEDORP)

In private practice, you might need to pay this person extra to keep on top of the outcomes research. Usually it is best to have at least 2 people on this team: an MD and someone else who is interested in outcomes research.

In private practice, you might need to pay this person extra to keep on top of the outcomes research. Usually it is best to have at least 2 people on this team: an MD and someone else who is interested in outcomes research.

2. Establish a budget. At Harvard, my initial research budget was $0! But I knew this was super important so I put an add on Craig’s list for a research fellow. I think that was free at the time. More than 30 people responded even though I made it clear the budget was $0. But the name Harvard was a big draw. Over time, my chairman, Dr. Fredrick Jakobiec and later Dr. Joan Miller, were incredibly generous in providing me with funds to do outcomes research until I could get my first grant. They both helped me get those first grants which made all the difference in being affirmed that we were doing something worthwhile.

3. Find a research fellow. At Harvard, my first research fellow made almost no money initially until I got a grant. He helped make the database in to a large source of information that allowed us to publish multiple studies. He is not an Assistant Professor at Harvard.

There are many students out there that would love to have a chance to publish or even do some research. When my fellow and I started, we did not know exactly how we should do things, but all it took was an interest in helping patients and finding the truth in outcomes research. Know that the majority of outcomes research involves data entry. We started when everything was in paper charts, so my research fellow and I would have stacks of charts in my office. The Medical Records department did not like us very much as we would periodically give them a list of 200 charts they had to pull.

It should be easier now, and it is, but it is a TRAVESTY that most electronic medical record systems do not let you populate directly into an excel or SPSS database. We are trying as I speak to get this to work with Medflow through a friend that can code and got the API from Medflow: but this is a bear of work!

Till this happens, we hired a student to manually put in all the data from our EMR into our spreadsheets. It is tedious, but the results are amazing.

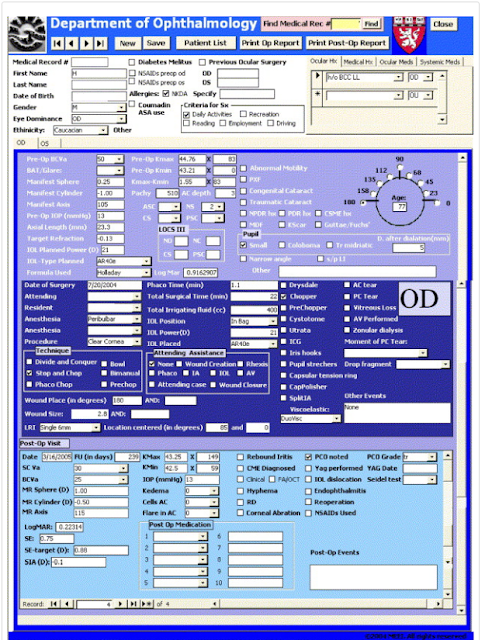

3. Set up a database: There are many ways to do this. At Harvard we started with a simple Excel file and years later moved to SPSS. An example of an initial excel database is below in the Expanded Section.

a. Decide what is important to you and your patients: Establish a hypothesis or multiple ones. What do you want to know? Do you want to finally know what your Surgically Induced Astigmatism really is? Write it on the database. This is the most important step. It is important to get as much data points if your are in this for the long run. If you are doing outcomes research to satisfy a mandate, then putting just the ones that are asked is a good start. But inevitably, we found that there will be questions once you have started that you wished were in the original spreadsheet. And going back to find the answer means more time, so it is best to get it all down the first time.

b. Collect the data: this is the manual plugging in of data (for now for most EMRs). This is a temporary issue as soon [I estimate it will take a law for this to happen, but I hope this happens within the next 5 years, but it will likely be 10 years], all EMRs will be required to allow you to extract the data as you want, when you want.

c. Analyze the data. Just look at the data. See what your average post op month 1 vision is. Just scroll through the database and look. See if you can start to form multiple hypotheses.

4. Find a statistician who can help you see if your hypothesis or hypotheses are valid or incorrect. For some of the basic analysis, a research fellow with no stats background can figures out how to see what your SIA is or your average post op month 1 vision is. But for more involved analysis, you will need a statistician ideally who knows about ophthalmology. They are out there and now easier to find with the internet. Furthermore you do not have to sit down with them for hours like we used to have to do.

At Harvard, our now world famous statistician initially wanted to be paid by the hour or to be listed on the paper. Towards the end of my time there, she wanted both: that was painful. But she was great.

Currently, our fellow is excellent at statistics but is able to access help from the Statistics Department at Georgetown.

5. Write it up. Don’t be scared if you have never written a paper in your life. Just write down your results, analyze your results and write them down, write the conclusion, and write the introduction and title at the end. Add references. Have a couple of respected colleagues read it over. Submit it.

After a few times writing up your outcomes work, it becomes a process like putting a puzzle together, which can actually be enjoyable. Likely the reason it is most enjoyable is because you are revealing truths about yourself and your practice and striving to be the best for your patients who you love and adore.

Expanded Version:

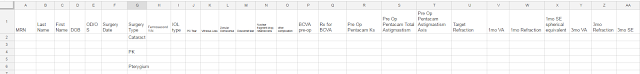

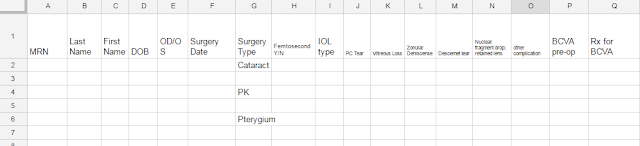

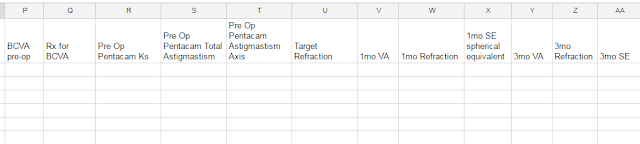

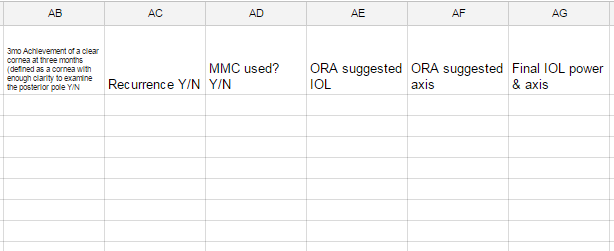

Here is a sample of an initial excel spreadsheet with the data you could collect.

My initial spreadsheet just gives an idea of what we would want to collect and for what surgeries.

Here is a revised version example:

For now, each doctor and surgeon will be expected to provided outcomes data whether they like it or not. We have a team set up to do this for our practice. If you have questions about this, please let us know.

Our research data base at Harvard had many more components than what is noted above.

The big issue now is that thousands of doctors and surgeons will be scrambling to assess their outcomes. Everyone will format their outcomes data in different ways. Data sets might not be formatted in a way for them to merge together easily for a meta-analysis. Many will collect the same data, but most will have variations in what data points are assessed.

It would be great if the American Academy of Ophthalmology, ASCRS, or some other organization or company could make things more uniform that is not government or insurance related so doctors and surgeons would be more willing to hand over their data to benefit patients and themselves. This is is full of issues as many of us know: security of data, HIPPA issues, the expense.

For now, each doctor and surgeon will be expected to provided outcomes data whether they like it or not. We have a team set up to do this for our practice. If you have questions about this, please let us know.

Sandra Lora Cremers, MD, FACS