iStent: An Innovation in the Care of Glaucoma Patients: One of the Best Innovations in Eye Surgery in the last 5 years.

Glaucoma is damage to the optic nerve, which is the nerve (ie, like a tv cable) that connects the eye to the brain. If optic nerve damage is severe, patients begin to loose their peripheral vision first usually first. With time, the loss of vision proceeds to interfere with central vision. Glaucoma remains one of the leading causes of blindness in the world.

Before June 25, 2012, the only options to treat glaucoma were:

A. Drops: Prescription eye drops are available to lower intraocular pressures: Normal being <22 mmHg corrected for corneal thickness which on average is about 540-555 um (about half of a millimeter: thickness is checked with a handheld ultrasound device called a pachymeter. Of note, eye pressure is measured in millimeters of mercury (mm Hg). Normal eye pressure ranges from 12-22 mm Hg, and eye pressure of greater than 22 mm Hg is considered higher than normal. When the IOP is higher than normal but the person does not show signs of glaucoma, this is referred to as ocular hypertension. If the highest eye pressure ever recorded (I call this Tmax for Maximum pressure on Tonometry [the instrument we use to measure pressure])is less than 21 or 22mmHg AND the patient has signs of nerve damage and glaucoma, this is called Normal Tension Glaucoma.

BEST WAY TO USE PUT IN EYE DROPS

By the way: a little pearl on how to put eye drops in for someone who can’t help squeeze the eye shut (i.e. children), or someone who has a very shaky hand and is worried about hitting their eyeball with the tip of the bottle [which we never want to do as it can cause a corneal abrasion]:

a) Tilt head back parallel to the floor as shown in this photo.

a) Tilt head back parallel to the floor as shown in this photo.

b) If the patient cannot open the eye so one can see the drop hit the surface of the eyeball (which is the best way to put in an eye drop), then let the patient close the eyes naturally …

c) Put a drop in the corner of the eye, then ask the patient to open the eyes without moving the head to assure the drop fell into the eyeball’s cul de sac. Patient should say they “felt the drop go in.” If you are not sure for whatever reason, and your eyeMD says you need to be sure it goes in [ie, for a serious eye infection or very severe glaucoma], then if your eyeMD says to do it again, put another drop in: you cannot overdose on eye drops in most cases but check with your eyeMD if you are having to put in multiple drops “to be sure it went in.” Always check with your eyeMD if you are doing this with steroid drops or drops that contain beta blockers [ie Timolol or Timoptic, Cosopt].

d) To help keep the drops in the eye area for longer and avoid the taste of some drops, ALWAYS place pressure in punctal area as shown below: there is a canal that goes from the eye and drains in the nose. By using Punctal Occlusion, you increase the effectiveness of the drop (See Reference 5 below).

e) Close the eyes and apply punctal pressure. Some studies note: “Closure of the lids prevents loss of solutions by inhibiting flow into the lacrimal outflow system, enhances entrapment of fluid under the lid, and increases the volume of extraocular fluid. Pressure on the lacrimal sac, especially with lids closed, is a most effective method to increase ocular contact time.” Most recommend doing this for 5 Minutes! Who has 5 minutes these days. Thus the need for another option to treat glaucoma patients: Jump to D if you want to get to the point of this article.

Thus to review:

1. Primary Open Angle Glaucoma (POAG): you have reproducible signs of optic nerve head damage on tests evaluating the function, appearance, and nerve fiber layer thickness of the optic nerve AND your highest eye pressure (Tmax) has been noted to be higher than 22mmHg.

2. Normal Tension Glaucoma (NTG): you have reproducible signs of optic nerve head damage on tests evaluating the function, appearance, and nerve fiber layer thickness of the optic nerve AND your highest eye pressure (Tmax) has been noted to ALWAYS be lower than 22mmHg before any drops were started or procedures performed.

3. Ocular Hypertension (OHTN): Eye pressure IOP is higher than normal but the person does not show signs of glaucoma.

4. Pigmentary Glaucoma: High Eye pressure from pigment release inside the eye (either from a history of pigment dispersion syndrome [a genetic condition which is usually preventable if caught early, where the iris rubs against the lens of the eye and releases pigment] or Pseudoexfoliation (PXF [an age-related systemic microfibrillopathy: which mean there is a gradual deposition of fine, strange, fibrillary residue or microscopic strands of tissue on the lens of the eye and iris pigment epithelium, mainly on the lens capsule, ciliary body, zonules, corneal endothelium and iris: it “clogs” the drain of the eye and can lead to high eye pressures].

5. Uveitic Glaucoma: Glaucoma due to uveitis: an inflammation inside the eye involving the uveal tract or pigmented tract: iris, ciliary body, choroid.

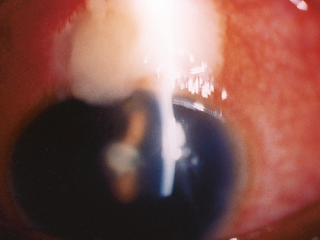

B. Trabeculectomy (Trab for short): an invasive procedure (since the introduction of the iStent, some MDs would now say a Trab and Shunt [see C] are slightly barbaric) where the surgeon creates a connection between the inner eye fluid to an outer pouch sitting on top of the eye ball called a bleb. Since Trabeculectomy remains one of only a few options to save a patient’s sight, it is still required in many patients unfortunately. It works well for the majority of patients but has a list of potential complications including loss of the eyeball from infection. Drops do not have this risk.

B. Trabeculectomy (Trab for short): an invasive procedure (since the introduction of the iStent, some MDs would now say a Trab and Shunt [see C] are slightly barbaric) where the surgeon creates a connection between the inner eye fluid to an outer pouch sitting on top of the eye ball called a bleb. Since Trabeculectomy remains one of only a few options to save a patient’s sight, it is still required in many patients unfortunately. It works well for the majority of patients but has a list of potential complications including loss of the eyeball from infection. Drops do not have this risk.

Endophthalmitis and severe blebitis following trabeculectomy. Epidemiology and risk factors; a single-centre retrospective study

- Örjan Wallin1,

- Abdullah M. Al-ahramy1,†,

- Mats Lundström2 and

- Per Montan1,*

Article first published online: 11 SEP 2013

The literature concerning endophthalmitis following cataract surgery is vast and consists at best of large-scale prospective investigations (Fisch et al.

1991; Sandvig & Dannevig

2003; Lundström et al.

2007; Friling et al.

2013). In contrast, epidemiological studies on infection following trabeculectomies analysing more than 2000 operations are scarce (Aaberg et al.

1998). The reason for this is obvious; the volume of filtering surgeries is much lower than that of cataract operations. This calls for longer observation periods to generate solid incidence figures for such a rare complication as postoperative endophthalmitis (PE). Another phenomenon making long-term follow-up essential after bleb surgery is the high proportion of delayed infections, either manifested as blebitis or as frank PE, with an onset ranging from months to up to several years after the procedure. This consequently makes the epidemiological surveillance difficult.

The aim of this study was to investigate the incidence of PE and severe blebitis following trabeculectomy performed at a high-volume surgical centre in Sweden. In addition, a case–control study was carried out to identify risk factors for postoperative infection.

The last photo above shows a severe bleb infection causing endophthalmitis.

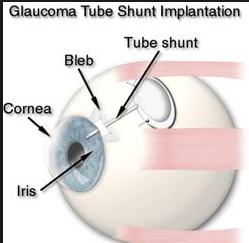

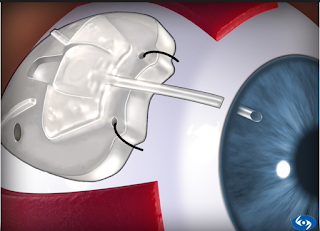

C. Tube or Shunt

A more invasive procedure where a silicone tube is inserted into the eye and attached to a plate that sits on the surface of the eyeball to help filter the fluid in the eye properly. This is usually very effective in lowering eye pressure but there are higher risks that the pressure can go too low and cause vision problems for choroidal detachments (part of the wall of the eyeball collapses inside) and infection than with trabeculectomy.

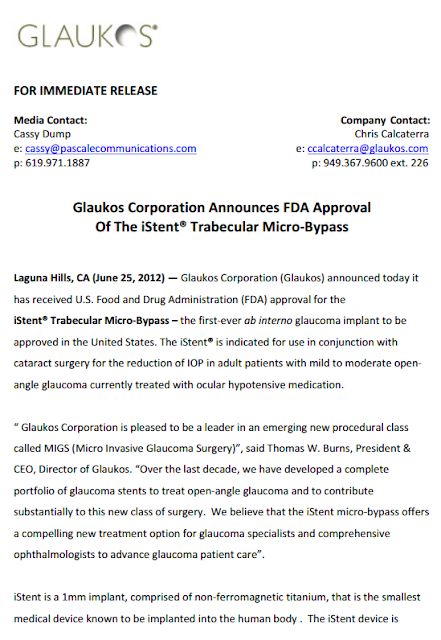

D. iSTENT:

So imagine the delight of eye surgeons everywhere when the FDA approved the iStent in 2012. At last there was another option to treat our patients who have glaucoma but cannot tolerate their drops or are not controlled on their drops.

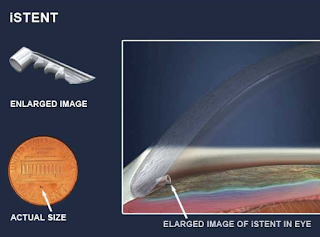

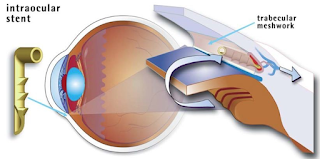

The iStent is a surgical-grade nonferromagnetic titanium micro-bypass stent preloaded in a single-use, sterile inserter designed to allow the micro-targeted placement into Schlemm’s canal (ie, the drain of the eye).

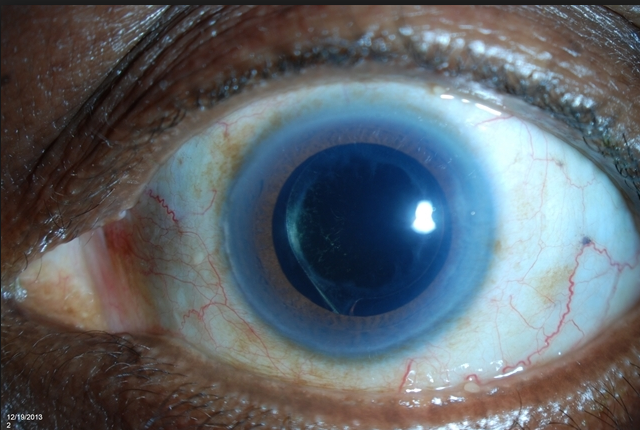

The iStent is the smallest medical device ever approved by the FDA and is placed in your eye during cataract surgery. It is so small, you won’t be able to see or feel it after surgery but it will be continuously working to help reduce your eye pressure.

There is little added risk to insert the iStent when performed at the time of cataract surgery, which currently is the case: they must be performed together. The key risk of any intraocular surgery is the risk of an eye infection which could lead to a loss of vision or loss of the eye. That risk currently with cataract surgery is about 0.08% – 0.68% in the literature. It is lower when intracameral cefuroxime is given, meaning when antibiotics are injected into the front chamber inside the eye (See Reference 5 below).

The other risk is that the iStent does not work well enough for the patient and eye drops need to be continued or a Trab or Tube needs to be placed.

Thus the news that studies are on the way that would allow surgeons to place more than 1 iStent is very exciting. Hopefully this might be the beginning of the end of Trabs and Tubes!

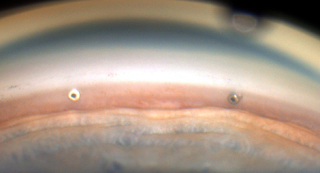

Can you see the microscopic iStent here? This patient had cataract surgery so you can see the intraocular implant (IOL) through a dilated pupil. But can you see the iStent? See below if you need a clue.

Look at 2:30 clock hours. It is hard to see it due to this patients Arcus Senilus (the white ring around the cornea usually due to aging, genetics, and/or a high systemic cholesterol level).

Source: Glaukos

Glaukos announced that a new international study, published in the December 2015 issue of

Clinical Ophthalmology, showed that patients achieved significantly greater reduction in IOP at 18 months with use of each additional iStent Trabecular Micro-Bypass Stent, according to a company news release. These results demonstrate the potential of implanting one or more iStents as titratable therapy to achieve different levels of IOP reduction.

In this prospective, randomized study conducted by multiple surgeons at a single investigational site, 119 subjects with open-angle glaucoma and preoperative unmedicated IOP between 22 mmHg and 38 mmHg received one, two or three iStents in a standalone procedure. In this study design, selection for the number of stents was based on randomization and not on each glaucoma patient’s specific needs. The study design included a primary efficacy endpoint of ≥20% IOP reduction at 12 months from baseline unmedicated IOP without use of prescription eye drops or secondary glaucoma procedures. The secondary efficacy endpoint was IOP ≤18 mmHg at 12 months without use of prescription eye drops or secondary glaucoma procedures.

Approximately 89%, 90% and 92% of the one-, two- and three-stent groups met the primary and secondary endpoints, respectively. Importantly, nearly two-thirds of patients on single-stent therapy alone achieved postoperative pressures of ≤15 mmHg without medication at 12 months. Moreover, at 18 months, mean unmedicated IOP was 15.9 mmHg, 14.1 mmHg and 12.2 mmHg in the one-, two- and three-stent groups, respectively. No intraoperative ocular adverse events occurred and safety data were similar across all stent groups. By month 18, four eyes had undergone cataract surgery due to progression of cataract.

“The results of this study underscore not only the significant IOP-lowering capability of a single iStent in a standalone procedure, but also the benefit of using additional iStents to achieve even greater levels of sustained IOP reduction with reduced reliance on prescription eye drops,” L. Jay Katz, MD, director of the Glaucoma Service at the Wills Eye Hospital and professor of ophthalmology at Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia, said in the news release. “The results demonstrate the future role and potential of multiple-stent implantation as titratable glaucoma therapy, allowing surgeons to tailor their treatments depending on the patient’s particular disease severity and progression.”

Sponsored by Glaukos, this study was intended to comparatively assess one, two and three stents as a sole therapy in open-angle glaucoma patients, and is believed to be the first ever ophthalmic medical device study to randomize subjects to receive single versus multiple surgical devices. It is designed for five-year postoperative follow-up.

Made of heparin-coated titanium, the iStent is inserted through a small corneal incision and placed into Schlemm’s canal, a circular channel in the eye that collects aqueous humor and eventually delivers it into the bloodstream. If the aqueous humor cannot drain appropriately through the trabecular meshwork and Schlemm’s canal, the pressure within the eye (IOP) can become elevated. Once inserted, the iStent restores the natural outflow pathways for aqueous humor and provides sustained IOP reduction.

The iStent is approved in the European Union and certain other international markets for use either in combination with cataract surgery or as a standalone procedure in phakic and pseudophakic eyes. In the United States, the iStent is indicated for use in conjunction with cataract surgery for the reduction of IOP in adult patients with mild-to-moderate open-angle glaucoma currently treated with ocular hypotensive medication.

Glaukos’ product portfolio also includes the iStent inject Trabecular Micro Bypass Stent, which relies on a similar method of action as iStent but features two stents preloaded in an auto-inject mechanism. It is already approved for commercial use in the European Union, Canada and Australia, and an initial commercial launch of iStent inject is currently underway in Germany. Glaukos is conducting U.S. IDE clinical trials for two versions of the iStent inject, one in combination with cataract surgery and another for use as a standalone procedure in glaucoma patients who are not undergoing concurrent cataract surgery.

2. FDA NEWS RELEASE

For Immediate Release: June 25, 2012

Media Inquiries: Sarah Clark-Lynn, 301-796-9110,

sarah.clark-lynn@fda.hhs.gov

Consumer Inquiries: 888-INFO-FDA

FDA approves first glaucoma stent for use with cataract surgery

Today, the iStent Trabecular Micro-Bypass Stent System, Model GTS100R/L, was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. This is the first device approved for use in combination with cataract surgery to reduce pressure inside the eye (intraocular pressure) in adult patients with mild or moderate open-angle glaucoma and a cataract who are currently being treated with medication to reduce intraocular pressure.

Glaucoma, a group of diseases that damage the optic nerve, is one of the leading causes of vision loss and blindness. Open-angle glaucoma is the most common form of glaucoma.

In a healthy eye, clear fluid flows continuously into and out of the anterior chamber of the eye, the fluid filled space between the iris and the cornea. Fluid drains from the anterior chamber through a meshwork of tissue along the outer edge of the iris, where the iris and cornea meet, and into a canal called Schlemm’s canal that drains the fluid out of the eye.

In open-angle glaucoma, the meshwork may become blocked or drain too slowly. Since fluid cannot leave the eye or leave it quickly enough, pressure builds up inside the eye and can rise to a level that may damage the optic nerve, resulting in vision loss.

The iStent is a small titanium tube placed through the meshwork of tissue. This creates an opening between the eye’s anterior chamber and Schlemm’s canal that allows fluid to drain, potentially decreasing intraocular pressure.

“The iStent is a new option that may be considered in the treatment of open-angle glaucoma in patients needing cataract extraction,” said Christy Foreman, director of the Office of Device Evaluation at FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health. “This option may be considered earlier in the disease process than some other types of surgical glaucoma treatments.”

The FDA reviewed effectiveness data from a study total of 240 eyes for 239 participants (one participant had both eyes evaluated). The FDA also reviewed the safety data for these and an additional 50 participants. At one year following the procedure, 68 percent of participants with the iStent had the study target pressure of 21 millimeters of mercury or lower without the use of eye pressure-lowering medication, compared to 50 percent of participants who underwent cataract surgery alone.

Because the iStent was implanted in combination with cataract surgery during the study, it was not possible to attribute all complications in the iStent-implanted participants to just the cataract procedure or just the iStent device. Among the participants who underwent surgery to implant the iStent, the following complications were directly linked to the device: unsuccessful or difficulty implanting, poor positioning of the stent, the stent touching the iris or cornea during surgery, the device being dropped into the eye prior to implantation, and the stent becoming blocked after surgery.

The iStent Trabecular Micro-Bypass Stent System is manufactured by Glaukos Corporation of Laguna Hills, Calif.

3.

4.

Abstract

Purpose

To review the effects of nasolacrimal occlusion (NLO) and eyelid closure (ELC) on the ocular and systemic absorption of topically applied glaucoma medications and emphasize the need for the universal application of these techniques during patient treatment and in clinical studies of topically applied glaucoma medications.

Methods

Following a review of data suggesting great clinical benefit from NLO and ELC, the absence of inclusion of these simple techniques in published studies of topical glaucoma medications is identified. The effect of this oversight on these studies is noted with reference to each of the 5 major groups of glaucoma medications.

Results

A review of the literature suggests that NLO and ELC improve intraocular penetration of topically applied glaucoma medications and discourage systemic absorption. The US Food and Drug Administration and the National Institutes of Health discourage the inclusion of these techniques in studies of the efficacy and toxicity of topically applied glaucoma medications. Consequently, all glaucoma studies reported in the literature lack the inclusion of these techniques for 5 minutes. This omission has major implications for patient informed consent, study protocol consistency, and the value of clinical studies, and directly affects the therapeutic index of glaucoma medications in unpredictable and undesirable ways. The undesirable influence on the therapeutic index of each drug influences the safety and efficacy and has implications for the cost of medical treatments, the reproducibility of clinical study results, and dosing regimens, including those of combination therapy, as reflected in the peer-reviewed literature.

Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 2008 Dec; 106: 138–148.

The Importance of Eyelid Closure and Nasolacrimal Occlusion Following the Ocular Instillation of Topical Glaucoma Medications, and the Need for the Universal Inclusion of One of these Techniques in All Patient Treatments and Clinical Studies

Abstract

Purpose

To review the effects of nasolacrimal occlusion (NLO) and eyelid closure (ELC) on the ocular and systemic absorption of topically applied glaucoma medications and emphasize the need for the universal application of these techniques during patient treatment and in clinical studies of topically applied glaucoma medications.

Methods

Following a review of data suggesting great clinical benefit from NLO and ELC, the absence of inclusion of these simple techniques in published studies of topical glaucoma medications is identified. The effect of this oversight on these studies is noted with reference to each of the 5 major groups of glaucoma medications.

Results

A review of the literature suggests that NLO and ELC improve intraocular penetration of topically applied glaucoma medications and discourage systemic absorption. The US Food and Drug Administration and the National Institutes of Health discourage the inclusion of these techniques in studies of the efficacy and toxicity of topically applied glaucoma medications. Consequently, all glaucoma studies reported in the literature lack the inclusion of these techniques for 5 minutes. This omission has major implications for patient informed consent, study protocol consistency, and the value of clinical studies, and directly affects the therapeutic index of glaucoma medications in unpredictable and undesirable ways. The undesirable influence on the therapeutic index of each drug influences the safety and efficacy and has implications for the cost of medical treatments, the reproducibility of clinical study results, and dosing regimens, including those of combination therapy, as reflected in the peer-reviewed literature.

Conclusions

Patients should use NLO or ELC for 5 minutes following eye drop treatment with topically applied glaucoma medications. Furthermore, it is essential that these techniques be included in all clinical studies of topically applied glaucoma medications to ensure the most favorable therapeutic index and its accurate determination. This will also help provide the most consistent, reliable, and reproducible study results.

5.

Risk factors for endophthalmitis after cataract surgery: Predictors for causative organisms and visual outcomes.

Abstract

PURPOSE:

To investigate visual outcome, bacteriology, and time to diagnosis in groups identified as being at risk for endophthalmitis followingcataract surgery.

SETTING:

Swedish National Cataract Register.

DESIGN:

A retrospective review of postoperative endophthalmitis and control cases reported from 2002 to 2010.

METHODS:

Three identified risk groups for endophthalmitis confirmed in previous multivariate models were organized in such a way that the highest level of significance determined the allocation of cases that belonged to more than one group. Control cases of the entire database were arranged in the same manner.

RESULTS:

Of the 244 endophthalmitis cases occurring in 692 786 surgeries, 148 did not belong to any risk group, whereas the remaining cases were part of the following groups at risk: nontreatment with intracameral antibiotic (n = 22), communication with vitreous (n = 18), and age 85 years or more (n = 56). Cefuroxime was the intracameral antibiotic used in 99% of treated cases. Cases sustaining a communication with vitreous were found to have the worst visual prognosis. Among causative organisms, Gram-positive bacteria were significantly more frequent in cases with a communication with vitreous, whereas staphylococci and Gram-negative results were more common in patients aged 85 years or more than in nonrisk patients.

CONCLUSION:

Limiting the size of the risk groups by giving a prophylactic intracameral antibiotic to every single patient and by intervening earlier in the course of cataract development appear to be first steps in further reducing the endophthalmitis rate. Adjustments of the intracameral regimen may be advantageous in some risk groups.

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE:

None of the authors has any financial or propriety interest in any material or method mentioned.

a) Tilt head back parallel to the floor as shown in this photo.

a) Tilt head back parallel to the floor as shown in this photo. B. Trabeculectomy (Trab for short): an invasive procedure (since the introduction of the iStent, some MDs would now say a Trab and Shunt [see C] are slightly barbaric) where the surgeon creates a connection between the inner eye fluid to an outer pouch sitting on top of the eye ball called a bleb. Since Trabeculectomy remains one of only a few options to save a patient’s sight, it is still required in many patients unfortunately. It works well for the majority of patients but has a list of potential complications including loss of the eyeball from infection. Drops do not have this risk.

B. Trabeculectomy (Trab for short): an invasive procedure (since the introduction of the iStent, some MDs would now say a Trab and Shunt [see C] are slightly barbaric) where the surgeon creates a connection between the inner eye fluid to an outer pouch sitting on top of the eye ball called a bleb. Since Trabeculectomy remains one of only a few options to save a patient’s sight, it is still required in many patients unfortunately. It works well for the majority of patients but has a list of potential complications including loss of the eyeball from infection. Drops do not have this risk.