Dry eye symptoms can vary between patients. This is a list of symptoms in order of most common presentation in my dry eye practice.

1. Burning: burning is always from dryness (which is most often due to decreased meibomian gland oil in the tear film).

A. The most common cause of chronic burning is MGD: meibomian gland dysfunction which means one’s oil is not being incorporated into the tear film properly: this can occur for many reasons:

a) decrease number of oil glands

b) orifice of gland or any part of gland is scared and preventing the oil from coming out (like in patients who used Accutane or have Ocular rosacea)

c) the composition of the oil is not perfect

Most patients note actual dryness or sticking of eyelids

B. The second most common cause of burning is from Aqueous Tear Deficiency (ATD), which means the Lacrimal Gland does not produce enough Aqueous (or the watery part of the tear). This can also occur for many reasons:

a) underlying inflammation in the lacrimal gland from autoimmune disease (Sjogren’s syndrome, Rheumatoid Arthritis, Lupus, etc), previous Accutane use.

b) previous surgery/trauma

C. The 3rd most common cause of chronic burning is previous Laser refractive surgery or corneal surgery, such as LASIK, PRK, corneal transplant. This occurs usually because the corneal nerves have been cut which in some patients can lead to a cascade of inflammation that cause the nerve fibers to keep firing causing a burning pain or just pain.

D. For Acute Burning:

a. The most common cause of acute burning is not blinking enough & an acute drying out of the tear film: don’t try this but you can prove it to your self by not blinking for a couple of minutes.

b. Chemical in the eye: an abnormal ph on the eye’s surface will cause burning which usually resolves once the ph is brought back to 7.0.

2. Foreign Body Sensation: usually due to an abnormal combination of oil, and aqueous, mucin which prevents a smooth covering over the eye of the tear. Also scar tissue on the eye’s surface and/or meibomian glands can cause this sensation. Demodex mites and bacteria clumps can also cause this.

3. Grittiness: usually due to an abnormal combination of oil, and aqueous, mucin which prevents a smooth covering over the eye of the tear. Also scar tissue on the eye’s surface and/or meibomian glands can cause this sensation. Demodex mites and bacteria clumps can also cause this.

4. Dryness: “they just feel dry” or “my eye stick together”

5. Tearing: this is from a Reflex. The eye senses dryness and sends a signal to the glands to produce reflex tears which still do not have the right combination of oil, and aqueous, mucin

6. Itching: Allergies and Dry eyes go hand in hand. Allergies can destroy meibomian glands thru chronic inflammation. Dry eyes make allergic conjunctivitis worse likely because the tear cannot properly flush out allergens. A vicious cycle ensues. It is important to keep allergies under control with the options mentioned below. Remember Warm Heat is good to clean glands and lashes. Cold/ice compresses help with Allergies, redness, itching. We sometimes need to use both: 1st heat to clean and then cold after to keep inflammation/allergic reactions low.

7. Redness: never ignore eye redness. It means there is inflammation and scar tissue will form somewhere if not controlled.

8. Chronic Pain: this is less common but from reasons above.

9. Vision Loss: rare. Severe dry eye can lead to vision loss requiring a corneal transplant or even severe eye infections.

Step Ladder Approach to Chronic Eye Itching:

Allergy Treatments

Dry Eye Syndrome (DES), is the essentially the same as Dry Eye Disease (DED). It is also known as Keratoconjunctivitis Sicca (KCS), and Keratitis Sicca and even sometimes as just, “Dry Eye.” Dry Eye Syndrome is a multifactorial disease of the tears and the ocular surface that results in discomfort which can range from mild irritation to eye burning and go on to terrible pain. It also causes visual disturbances which can begin as blurry vision from time to time and to progress to loss of vision in severe cases. It can cause tearing (usually due to a reflex), redness (which is a sign of inflammation that is leaving behind scar tissue in the cells of the eye), itchiness (which is often due to allergy or demodex mites and/or bacteria on the eyelash margin), and tear film instability (which causes fluctuating vision and the feeling that your glasses are the wrong prescription. All of these issues have the potential to cause significant eye surface damage.

The most unhappy medical patients I have ever seen are those with cancer with metastatic bone pain. They need iv drips with morphine. Not too far down the list on unhappy patients are my patients with severe dry eye who have terrible pain with each blink of their eye. They ignored their discomfort for years and now regret having ignored their eyes.

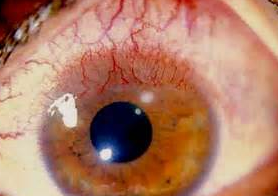

Initially, one or both eyes might be a little red and feel irritated.

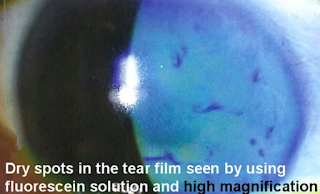

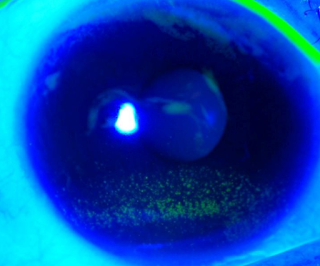

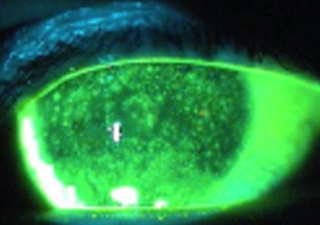

This is what your eyeMD is looking under the microscope.

As the disease worsens, the signs of dry eye under the microscope worsen. This is called Superficial Punctate Keratitis or SPK. This means the cornea’s front layer of cells are dead and not doing their job of protecting the inner nerve layer from discomfort and pain. The front layer or epithelial layer can grow back but they often need help to do so. It is imperative that we help them grow back. Otherwise, more inflammation develops and the disease worsens. It is a vicious cycle that must be stopped.

Treatment Options: There are many options. One of the best, we have seen if initial treatments do not resolve symptoms is the Lipiflow machine.

Sandra Lora Cremers, MD, FACS

I revised the Wilkipedia page on its website a bit but was very impressed with the information provided on dry eye.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dry_eye_syndrome

Dry eye syndrome

| Dry eye syndrome | |

|---|---|

| dry eye, keratoconjunctivitis sicca, dry eye disease, keratitis sicca | |

Diffuse lissamine green staining in a person with severe dry eye.[1]

|

|

| Classification and external resources | |

| Specialty | ophthalmology |

Signs and symptoms[edit]

Causes[edit]

Decreased tear or excessive evaporation[edit]

Additional causes[edit]

Pathophysiology[edit]

Diagnosis[edit]

Prevention[edit]

Treatment[edit]

Environmental control[edit]

Rehydration[edit]

Autologous serum eye drops[edit]

Additional options[edit]

Medication[edit]

Fish and Omega−3 fatty acids consumption[edit]

Cyclosporin[edit]

Conserving tears[edit]

Other[edit]

Surgery[edit]

Prognosis[edit]

Epidemiology[edit]

Synonyms[edit]

Other animals[edit]

Dogs[edit]

- Cavalier King Charles Spaniel

- Bulldog

- Chinese Shar-Pei

- Lhasa Apso

- Shih Tzu

- West Highland White Terrier

- Pug

- Bloodhound

- Cocker Spaniel

- Pekingese

- Boston Terrier

- Miniature Schnauzer

- Samoyed[50]

Cats[edit]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ Critser, Brice. “Lissamine green staining in keratoconjunctivitis sicca”. Eye Rounds. The University of Iowa. Retrieved 29 July 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h “Facts About Dry Eye”. NEI. February 2013. Retrieved 29 July 2016.

- ^ a b c Kanellopoulos, AJ; Asimellis, G (2016). “In pursuit of objective dry eye screening clinical techniques.”. Eye and vision (London, England). 3: 1. doi:10.1186/s40662-015-0032-4. PMC 4716631

. PMID 26783543.

. PMID 26783543. - ^ Tavares Fde, P; Fernandes, RS; Bernardes, TF; Bonfioli, AA; Soares, EJ (May 2010). “Dry eye disease.”. Seminars in ophthalmology. 25 (3): 84–93. doi:10.3109/08820538.2010.488568. PMID 20590418.

- ^ Messmer, EM (30 January 2015). “The pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment of dry eye disease.”. Deutsches Arzteblatt international. 112 (5): 71–81; quiz 82. doi:10.3238/arztebl.2015.0071. PMC 4335585

. PMID 25686388.

. PMID 25686388. - ^ Ding, J; Sullivan, DA (July 2012). “Aging and dry eye disease.”. Experimental Gerontology. 47 (7): 483–90. doi:10.1016/j.exger.2012.03.020. PMC 3368077

. PMID 22569356.

. PMID 22569356. - ^ Liu, NN; Liu, L; Li, J; Sun, YZ (2014). “Prevalence of and risk factors for dry eye symptom in mainland china: a systematic review and meta-analysis.”. Journal of ophthalmology. 2014: 748654. doi:10.1155/2014/748654. PMC 4216702

. PMID 25386359.

. PMID 25386359. - ^ Firestein, Gary S. (2013). Kelley’s textbook of rheumatology (9th ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier/Saunders. p. 1179. ISBN 9781437717389.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y “Keratoconjunctivitis Sicca”. The Merck Manual, Home Edition. Merck & Co., Inc. 2003-02-01. Retrieved 2006-11-12.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al“Keratoconjunctivitis, Sicca”. eMedicine. WebMD, Inc. January 27, 2010. Retrieved September 3, 2010.

- ^ a b c d “Dry eyes”. MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia. U.S. National Library of Medicine. 2006-10-04. Retrieved 2006-11-16.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z Michelle Meadows (May–June 2005). “Dealing with Dry Eye”. FDA Consumer Magazine. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Archived from the original on February 23, 2008.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u “Dry eyes”. Mayo Clinic. Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research. 2006-06-14. Retrieved 2006-11-17.

- ^ Sendecka M, Baryluk A, Polz-Dacewicz M (2004). “Częstość występowania zespołu suchego oka” [Prevalence and risk factors of dry eye syndrome]. Przegla̧d Epidemiologiczny (in Polish). 58 (1): 227–33. PMID 15218664.

- ^ Puéchal, X; Terrier, B; Mouthon, L; Costedoat-Chalumeau, N; Guillevin, L; Le Jeunne, C (March 2014). “Relapsing polychondritis.”. Joint, bone, spine : revue du rhumatisme. 81 (2): 118–24. doi:10.1016/j.jbspin.2014.01.001. PMID 24556284.

- ^ Cantarini, L; Vitale, A; Brizi, MG; Caso, F; Frediani, B; Punzi, L; Galeazzi, M; Rigante, D (February–March 2014). “Diagnosis and classification of relapsing polychondritis.”. Journal of autoimmunity. 48-49: 53–9. doi:10.1016/j.jaut.2014.01.026. PMID 24461536.

- ^ Zhou L, Zhao SZ, Koh SK, et al. (July 2012). “In-depth analysis of the human tear proteome”. Journal of Proteomics. 75 (13): 3877–85. doi:10.1016/j.jprot.2012.04.053. PMID 22634083.

- ^ a b c Karnati R, Laurie DE, Laurie GW (December 2013). “Lacritin and the tear proteome as natural replacement therapy for dry eye”. Experimental Eye Research. 117: 39–52. doi:10.1016/j.exer.2013.05.020. PMC 3844047

. PMID 23769845.

. PMID 23769845. - ^ Samudre S, Lattanzio FA, Lossen V, et al. (August 2011). “Lacritin, a novel human tear glycoprotein, promotes sustained basal tearing and is well tolerated”. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 52 (9): 6265–70. doi:10.1167/iovs.10-6220. PMC 3176019

. PMID 21087963.

. PMID 21087963. - ^ Vijmasi T, Chen FY, Balasubbu S, Gallup M, McKown RL, Laurie GW, McNamara NA (July 2014). “Topical administration of lacritin is a novel therapy for aqueous-deficient dry eye disease.”. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 55 (8): 5401–9. doi:10.1167/iovs.14-13924. PMC 4148924

. PMID 25034600.

. PMID 25034600. - ^ Fraunfelder FT, Sciubba JJ, Mathers WD (2012). “The role of medications in causing dry eye”. Journal of Ophthalmology. 2012: 285851. doi:10.1155/2012/285851. PMC 3459228

. PMID 23050121.

. PMID 23050121. - ^ Kaiserman I, Kaiserman N, Nakar S, Vinker S (March 2005). “Dry eye in diabetic patients”. American Journal of Ophthalmology. 139 (3): 498–503. doi:10.1016/j.ajo.2004.10.022. PMID 15767060.

- ^ Li H, Pang G, Xu Z (2004). “Tear film function of patients with type 2 diabetes”. Zhongguo Yi Xue Ke Xue Yuan Xue Bao. 26 (6): 682–6. PMID 15663232.

- ^ Millodot M (1978). “Effect of long term wear of hard contact lenses on corneal sensitivity”. Arch Ophthalmol. 96 (7): 1225–7. doi:10.1001/archopht.1978.03910060059011. PMID 666631.

- ^ Macsai MS, Varley GA, Krachmer JH (1990). “Development of keratoconus after contact lens wear. Patient characteristics”. Arch Ophthalmol. 108 (4): 534–8. doi:10.1001/archopht.1990.01070060082054. PMID 2322155.

- ^ Murphy PJ, Patel S, Marshall J (2001). “The effect of long term daily contact lens wear on corneal sensitivity”. Cornea. 20 (3): 264–9. doi:10.1097/00003226-200104000-00006. PMID 11322414.

- ^ Mathers WD, Scerra C (2000). “Dry eye; investigators look at syndrome with new model”. Ophthalmol Times. 25 (7): 1–3.

- ^ Peral A, Carracedo G, Acosta MC, Gallar J, Pintor J (September 2006). “Increased levels of diadenosine polyphosphates in dry eye”. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 47 (9): 4053–8. doi:10.1167/iovs.05-0980. PMID 16936123.

- ^ Tomlinson, A (April 2007). “DEWS Report, Ocular Surface April 2007 Vol 5 No 2” (PDF).

- ^ “American Academy of Ophthalmology Cornea/External Disease Panel. 2011 Preferred Practice Pattern® (PPP) guidelines”. October 2011.

- ^ a b “Dry eyes syndrome”. MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia. U.S. National Library of Medicine. 2006-10-04. Retrieved 2006-11-16.

- ^ a b c d Lemp MA. (2008). “Management of Dry Eye”. American Journal of Managed Care. 14 (4): S88–S101. PMID 18452372. Retrieved 2008-07-25.

- ^ Pucker AD, Ng SM, Nichols JJ (2016). “Over the counter (OTC) artificial tear drops for dry eye syndrome”. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2: CD009729. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009729.pub2. PMID 26905373.

- ^ Kojima, T.; Higuchi, A.; Goto, E.; Matsumoto, Y.; Dogru, M.; Tsubota, K. (2008). “Autologous Serum Eye Drops for the Treatment of Dry Eye Diseases”. Cornea. 27: S25–S30. doi:10.1097/ICO.0b013e31817f3a0e. PMID 18813071.

- ^ Pan Q, Angelina A, Zambrano A, Marrone M, Stark WJ, Heflin T, Tang L, Akpek EK (2013). “Autologous serum eye drops for dry eye”. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 10: CD009327. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009327.pub2. PMC 4007318

. PMID 23982997.

. PMID 23982997. - ^ Tatlipinar S, Akpek E (2005). “Topical cyclosporine in the treatment of ocular surface disorders”. Br J Ophthalmol. 89 (10): 1363–7. doi:10.1136/bjo.2005.070888. PMC 1772855

. PMID 16170133.

. PMID 16170133. - ^ Barber L, Pflugfelder S, Tauber J, Foulks G (2005). “Phase III safety evaluation of cyclosporine 0.1% ophthalmic emulsion administered twice daily to dry eye disease patients for up to 3 years”. Ophthalmology. 112 (10): 1790–4. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2005.05.013. PMID 16102833.

- ^ “FDA approves new medication for dry eye disease”. FDA. July 12, 2016. Retrieved 13 July2016.

- ^ a b Miljanović B, Trivedi KA, Dana MR, Gilbard JP, Buring JE, Schaumberg DA (2005). “Relation between dietary n-3 and n-6 fatty acids and clinically diagnosed dry eye syndrome in women”. Am J Clin Nutr. 82 (4): 887–93. PMC 1360504

. PMID 16210721.

. PMID 16210721. - ^ Rashid S, Jin Y, Ecoiffier T, Barabino S, Schaumberg M, Dana RD (2008). “Topical Omega-3 and Omega-6 Fatty Acids for Treatment of Dry Eye”. Arch Ophthalmol. 126 (2): 219–225. doi:10.1001/archophthalmol.2007.61. PMID 18268213.

- ^ Creuzot C, Passemard M, Viau S, Joffre C, Pouliquen P, Elena PP, Bron A, Brignole F (2008). “Improvement of dry eye symptoms with polyunsaturated fatty acids”. J Fr Ophthalmol. 29 (8): 868–73. PMID 17075501.

- ^ Oleñik A, Jiménez-Alfaro I, Alejandre-Alba N, Mahillo-Fernández I (2013). “A randomized, double-masked study to evaluate the effect of omega-3 fatty acids supplementation in meibomian gland dysfunction”. Clinical Interventions in Aging. 8: 1133–8. doi:10.2147/CIA.S48955. PMC 3770496

. PMID 24039409.

. PMID 24039409. - ^ “Restasis” (PDF). Allergan. January 2008. Retrieved 2008-07-23.

- ^ Dantal J, Hourmant M, Cantarovich D, Giral M, Blancho G, Dreno B, Soulillou JP (1998). “Effect of long-term immunosuppression in kidney-graft recipients on cancer incidence: randomised comparison of two cyclosporin regimens”. The Lancet. 351 (9103): 623–628. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(97)08496-1. PMID 9500317.

60 patients developed cancers, 37 in the normal-dose group and 23 in the low-dose group (p<0.034); 66% were skin cancers (26 vs 17; p<0.05). The low-dose regimen was associated with fewer malignant disorders but more frequent rejection.

- ^ “Sun Pharma Product List”. Sun Pharma. Archived from the original on 2007-02-13. Retrieved 2006-11-27.

- ^ Carter SR (June 1998). “Eyelid disorders: diagnosis and management”. American Family Physician. 57 (11): 2695–702. PMID 9636333.

- ^ Qiao, J; Yan, X (2013). “Emerging treatment options for meibomian gland dysfunction.”. Clinical ophthalmology (Auckland, N.Z.). 7: 1797–803. doi:10.2147/OPTH.S33182. PMC 3772773

. PMID 24043929.

. PMID 24043929. - ^ Ervin AM, Wojciechowski R, Schein O (2010). “Punctal occlusion for dry eye syndrome”. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 9: CD006775. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006775.pub2. PMC 3729223

. PMID 20824852.

. PMID 20824852. - ^ “Keratoconjunctivitis, Sicca”. The Merck Veterinary Manual. Merck & Co., Inc. Retrieved 2006-11-18.

- ^ a b c d e Gelatt, Kirk N. (ed.) (1999). Veterinary Ophthalmology (3rd ed.). Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 0-683-30076-8.

Further reading[edit]

- Maskin, Steven L. (2007-05-28). Reversing Dry Eye Syndrome: Practical Ways to Improve Your Comfort, Vision, and Appearance. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-12285-5.

- Latkany, Robert (2007-04-03). The Dry Eye Remedy: The Complete Guide to Restoring the Health and Beauty of Your Eyes. Hatherleigh Press. ISBN 978-1-57826-242-7.

- Patel, Sudi; Blades, Kenny (2003-04-10). The Dry Eye: A Practical Approach. Butterworth-Heinemann. ISBN 978-0-7506-4978-0.

- Geerling, Gerd; Brewitt, Horst (June 2008). Surgery for the Dry Eye: Scientific Evidence and Guidelines for the Clinical Management of Dry Eye Associated Ocular Surface Disease. S. Karger AG. ISBN 978-3-8055-8376-3.

- Asbell, Penny A.; Lemp, Michael A. (November 2006). Dry Eye Disease: The Clinician’s Guide to Diagnosis And Treatment. Thieme Medical Publishers. ISBN 978-1-58890-412-6.

External links[edit]

- Facts About the Cornea and Corneal Disease The National Eye Institute (NEI).

- Dry Eye Syndrome on NHS Choices

- Am.J.Managed Care – Dry Eye Disease: Pathophysiology, Classification, and Diagnosis

- Dry Eye Syndrome on eMedicine

- Dry Eye (Keratoconjunctivitis Sicca) from The Pet Health Library

- Nasolacrimal and Lacrimal Apparatus, The Merck Veterinary Manual