AIM:

Dry eye symptoms, resulting from insufficient tear fluid generation, represent a considerable burden for a largely underestimated number of people. We concluded from earlier pre-clinical investigations that the etiology of dry eyes encompasses oxidative stress burden to lachrymal glands and that antioxidant MaquiBright™ Aristotelia chilensis berry extract helps restore glandular activity.

METHODS:

In this pilot trial we investigated 13 healthy volunteers with moderately dry eyes using Schirmer test, as well as a questionnaire which allows for estimating the impact of dry eyes on daily routines. Study participants were assigned to one of two groups, receiving MaquiBright™ at daily dosage of either 30 mg (N.=7) or 60 mg (N.=6) over a period of 60 days. Both groups presented with significantly (P<0.05) improved tear fluid volume already after 30 days treatment. Schirmer test showed an increase from baseline 16.3±2.6 mm to 24.4±4.8 mm (P<0.05) with 30 mg MaquiBright™ and from 18.7±1.9 mm to 27.6±3.4 mm with 60 mg (P<0.05), respectively. Following treatment with 30 mg MaquiBright™ for further 30 days, tear fluid volume dropped slightly to 20.5±2.8 mm, whereas the improvement persisted with 60 mg treatment at 27.1±2.7 mm after 60 days treatment (P<0.05 vs. baseline).

RESULTS:

The burden of eye dryness on daily routines was evaluated employing the “Dry Eye-related Quality of life Score” (DEQS), with values spanning from zero (impact) to a maximum score of 60. Participants had comparable baseline values of 41.0±7.7 (30 mg) and 40.2±6.3 (60 mg). With 30 mg treatment the score significantly decreased to 21.8±3.9 and 18.9±3.9, after 30 and 60 days, respectively. With 60 mg treatment the DEQS significantly decreased to 26.9±5.3 and 11.1±2.7, after 30 and 60 days, respectively. Blood was drawn for safety analyses (complete blood rheology and -chemistry) at all three investigative time points without negative findings.

CONCLUSION:

In conclusion, while daily supplementation with 30 mg MaquiBright™ is effective, the dosage of 60 significantly increased tear fluid volume at all investigative time points and decreased dry eye symptoms to almost a quarter from initial values after two months.

Delphinidin-Rich Maqui Berry Extract (Delphinol®) Lowers Fasting and Postprandial Glycemia and Insulinemia in Prediabetic Individuals during Oral Glucose Tolerance Tests

, 1 , 2 , * , 3 , 1 , 1, 1 and 1

This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article has been

cited by other articles in PMC.

Abstract

Delphinidin anthocyanins have previously been associated with the inhibition of glucose absorption. Blood glucose lowering effects have been ascribed to maqui berry (Aristotelia chilensis) extracts in humans after boiled rice consumption. In this study, we aimed to explore whether a standardized delphinidin-rich extract from maqui berry (Delphinol) affects glucose metabolism in prediabetic humans based on glycemia and insulinemia curves obtained from an oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) after a challenge with pure glucose. Volunteers underwent four consecutive OGTTs with at least one week washout period, in which different doses of Delphinol were administered one hour before glucose intake. Delphinol significantly and dose-dependently lowered basal glycemia and insulinemia. Lower doses delayed postprandial glycemic and insulinemic peaks, while higher doses reversed this tendency. Glycemia peaks were dose-dependently lowered, while insulinemia peaks were higher for the lowest dose and lower for other doses. The total glucose available in blood was unaffected by treatments, while the total insulin availability was increased by low doses and decreased by the highest dose. Taken together, these open exploratory results suggest that Delphinol could be acting through three possible mechanisms: by inhibition of intestinal glucose transporters, by an incretin-mediated effect, or by improving insulin sensitivity.

1. Introduction

Frequent excessive postprandial glucose and insulin excursions represent a risk factor for developing diabetes, associated with impaired glucose tolerance (IGT) and impaired insulin tolerance (IIT), inflammation, dyslipidemia,

β-cell dysfunction, and endothelial dysfunction [

1]. The maintenance of healthy blood sugar levels and controlled carbohydrate metabolism is a rapidly growing concern in most developed countries and increasingly also in developing countries, due to the increased awareness of the hyperglycemia risks resulting from unhealthy diets and sedentary lifestyle [

2]. Further to dietary self-limitation and physical activity efforts, consumption of plant secondary metabolites may substantially contribute to improving carbohydrate and lipid metabolism [

3–

6].

Long term epidemiologic studies have pointed to dietary factors affecting the risk for developing diabetes. Investigation of data from the Nurses Health Studies (NHS) has resulted in interesting findings related to elevated regular consumption of different flavonoid classes and disease risk reduction [

7]. Higher consumption of anthocyanins was associated with lower risk for type II diabetes in US adults, based on the follow-up of 70359 women in the NHS (1984–2008) and 89201 women in NHSII (1991–2007) and also 41334 men in the Health Professionals Follow-Up Study (1986–2006) [

7]. Interestingly, this study found no significant correlation between other flavonoid subclasses and even total flavonoid consumption related to risk reduction for type II diabetes. A follow-up of the NHS II (93600 women) suggested that anthocyanin intake in the form of blueberries and strawberries would correlate with decreased myocardial infarction risk [

8]. A recent epidemiologic study suggests that regular higher intake of flavonoid species anthocyanins, flavones, and flavanones is associated with greater likelihood for good health and wellbeing in individuals surviving to older ages [

9].

Polyphenols are well described to exhibit inhibitory effects on

α-glucosidase and

α-amylase enzyme activities, thus delaying absorption of complex food carbohydrates [

10]. Particularly, the oligomeric proanthocyanidins potently delay hydrolysis of starchy foods to glucose, some of which appear to be more effective than acarbose medication [

11]. Consumption of anthocyanin-rich crowberry-fortified blackcurrant juice was described to attenuate significantly the postprandial blood glucose and insulin peak 90 minutes after glucose challenge, as compared to consumption of the same sugared beverage void of crowberry fortification [

12].

Delphinidin anthocyanins extracted from maqui berries (

Aristotelia chilensis), indigenous to Chile, are especially rich in glucoside and sambubioside derivatives. They have recently been ascribed to inhibit the sodium-glucose cotransporter type 1 (SGLT1) in rat duodenum. Delphinol, a proprietary maqui berry extract with a standardized content of 25% w/w delphinidin glycosides and 35% total anthocyanins, was found to significantly inhibit postprandial blood glucose 60 and 90 minutes after boiled rice intake [

13], with a single 200 mg dose before food consumption.

We here describe the results of open exploratory investigations on the effect of different doses of Delphinol on blood glucose and insulin in fasting conditions and postprandial effects after glucose ingestion, by applying a standard oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) in study participants with impaired glucose tolerance.

3.

4.

Scientists in Japan have made an important discovery that could revolutionize treatment for people suffering from dry eye syndrome.

Researchers found that an extract from the South American maqui berry can mitigate an underlying factor in dry eye syndrome—leading to significant improvements in symptoms and quality of life.

This represents a noteworthy improvement over commercial eye drops, which contain ingredients that some people are allergic to and only provide temporary relief.1

This unique oral approach is capable of relieving dry eyes by supporting natural tear production. That means you can take a single capsule once daily and experience soothing, youthful tear production day in and day out.

No other known natural oral treatment is capable of boosting aqueous tear fluid secretion and enhancing the function of the tear film like this. Patients with dry eye symptoms have found lasting improvements in eye comfort.

Compelling scientific studies demonstrate how maqui berry extract capitalizes on your body’s own natural mechanisms to boost tear output, restore comfort, and add a youthful shine to your eyes.

What Is Dry Eye Syndrome?

Dry eye syndrome occurs when your body doesn’t produce enough tears to keep your eyes moist. The resulting stinging, itching, sensitive eyes can lead to eye damage2—and can negatively impact your quality of life. A 2014 study found that people with dry eye syndrome had significantly lower scores on a standard mental health scale and lower quality of life.3,4

Dry eye syndrome is incredibly common, especially with advancing age and most especially in older women.5-7 Recent studies show that dry eye syndrome is on the rise both in America2,8 and around the world9—especially as more and more adults use computers, wear contact lenses, and undergo vision-correcting LASIK or cataract surgery.2,6,10-13

Untreated or inadequately treated dry eye syndrome can lead to damage to the cornea (the thin outermost region over the lens) and conjunctiva (the lubricating cell layer that lines the eyeball and inner surfaces of the lids).2 Making matters worse, corneal injuries (even a slight scratch) don’t heal as well when the eye is dry to begin with.14

In fact, dry eye syndrome can produce a vicious cycle in which poor tear production leads to inflammation that damages the eye surface and tear glands, leading to further loss of tear production and further damage.15

While no single biological cause of dry eye syndrome is yet known, we do know that chemical stresses and those induced by the high ultraviolet light exposure of the eye are at least in part to blame.16,17

But regardless of the trigger, dry eyes ultimately result from a simple imbalance: too little production of tears, or too rapid evaporation of tears on the surface of the eye.2,18,19

That’s what makes research into maqui berry extract so exciting: This extract directly enhances your body’s ability to make tears. This treatment has been found to address the cause of dry eyes—with research proving its use leads to long-lasting improvements in eye comfort.9

The Problem With Eye Drops

It can be difficult to imagine an oral treatment having such a profound impact on tear production. This is because mainstream medicine’s preferred treatments for dry eye syndrome are in the form of eye drops, both over-the-counter and prescription.

In fact, according to a recent estimate, Americans spend about a third of a billion dollars on over-the-counter eye drops, or “artificial tears,” each year.2 That’s a substantial investment in a product that produces only short-term relief but that has no long-lasting effect.20,21

Eye drops are the most recommended solution mainstream medicine offers for dry eye syndrome. This is problematic for multiple reasons. For starters, commercial, synthetic eye drops are often loaded with chemicals which may cause stinging and other unpleasant side effects.22,23 They often require frequent re-application in order to provide any relief at all. But that’s the least of their problems.

Some eye drops contain a vasoconstrictor in order to help with the discomfort of dry eyes. The main ingredient in such drops is usually tetrahydrozoline. While it has been shown to improve the redness associated with dry eyes after a single use, its effectiveness diminishes over a 10-day period, potentially encouraging overuse of the product.24

Chronic use of tetrahydrozoline has been shown to induce clinically important changes to the cornea in up to 27% of users.25 Worse, studies show that these eye drops can produce both acute and chronic conjunctivitis(inflammation of the conjunctiva, or mucosal layer that surrounds the eyeball).26 Tetrahydrozoline also has significant toxicity if ingested.27

Aside from being extremely expensive, prescription eye treatments such as Restasis® come with side effects ranging from eye redness and discharge to watery eyes, eye pain, feeling of a foreign body in the eye, itching, stinging, and blurred vision. In one study, 54.2% of subjects experienced eye discomfort while using these drops, and 4.2% discontinued use entirely because of side effects.28

Getting To The Bottom Of Dry Eyes

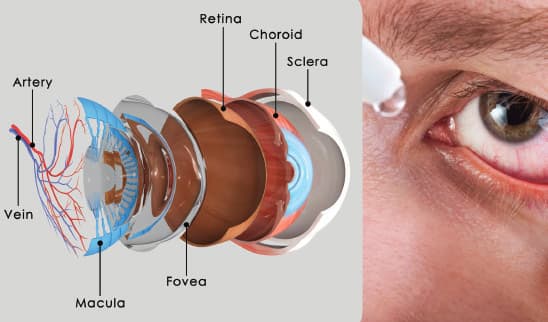

The super-thin layer of moisture that covers our eyes is crucial for proper eye lubrication and function. The tear film, as it is called, consists of three layers that are interactive: mucous, water, and oil.2

- Closest to the eye, directly over the cornea, lies the mucin layer, which provides lubrication and protection to the cornea. Insufficient mucous can lead to dry spots on the surface of the eye.2,29

- Next, moving outward, is the watery layer, which consists of water and salt, and is produced by the lacrimal glands.30

- At the outermost surface lies the oily lipid layer, which is secreted from glands on the edge of your eyelids called the Meibomian glands.31,32

Two leading characteristics of dry eye syndrome are either insufficient watery tear production from the lacrimal (tear-producing) gland or insufficient oil production from the Meibomian (oil-producing) glands.17 The oily layer covers the watery layer in order to prevent evaporation of water from the surface of the eye. Insufficient oil production, then, permits excessively rapid loss of watery tears from the layer below.

The most obvious and most natural way to relieve dry eye symptoms is to increase the rate of tear production in the lacrimal glands. Recent studies show that maqui berry extract can get to the root of dry eye syndrome by boosting tear production. This is accomplished from inside your body—no eye drops, no side effects, no discomfort—just soothing relief for dry, irritated eyes.

How Maqui Berry Extracts Boost Tear Production To Soothe Dry Eyes

Maqui berries are hardy natives of temperate rainforest regions of Chile and adjacent regions of southern Argentina.33-35 While little known in North America, these small berries have a long history of use in traditional medical systems of the region, where they have been used to treat diarrhea, inflammation, and fever.34,36

Japanese scientists were the first to isolate the active components and to show their power in fighting dry eye syndrome.9,37

Research now shows that a standardized extract of maqui berries (Aristotelia chilensis) contains plant chemical compounds (anthocyanins) known as delphinidins that have two powerful eye-protective actions:

- They inhibit damage to delicate tissues like the photoreceptor cells, caused by light stimulation, and

- They shield eye structures from constant exposure to reactive oxygen species.37

Together, these effects reduce chronic low-grade injury to the lacrimal glands, improving its ability to make tears. Additional mechanisms are not yet known, but animal studies show that delphinidins restore tear production by the lacrimal glands.19

Researchers examined the effects of maqui berry extract in a rat model of dry eye, in which animals’ blink reflex was suppressed to allow excessive evaporation from the eye surface. They found that pre-treatment with maqui berry extract significantly prevented reduction of tear secretion that was seen in a control group.19The larger the dose, the greater the effect of the extract, with 40 mg/kg per day demonstrating the maximum effect. And, while control animals experienced considerable damage to their corneas in terms of corneal opacity from the prolonged dry eye periods, the animals treated with maqui berry extract had clear eyes and no additional corneal opacities throughout the study period.

Human Study Demonstrates Long-Term Benefits

People who suffer from dry eye syndrome know that its symptoms—including burning, eye fatigue, sensitivity to light, blurred vision, and stringy mucous—can have a significant impact of their quality of life.2 With this in mind, Japanese researchers wanted to determine if maqui extract could positively impact quality of life and eye comfort in addition to increasing tear production. They found it can do both.

For this impressive study, 13 healthy volunteers with moderately dry eyes (according to Schirmer’s test) took either 30 or 60 mg of maqui extract daily and were evaluated at 30 and 60 days.9

After 30 days, subjects in both groups experienced similar improvement in tear production, with the 30 mggroup experiencing a 50% improvement, and the 60 mg group experiencing a 48% improvement. However, after 60 days, it became clear that the higher dose was more effective for long-term use.

After 60 days of treatment, tear production decreased towards baseline levels in the 30 mg group. By contrast, subjects taking 60 mg daily experienced a significant, sustained improvement from baseline of 45% in tear production.

Improvements In Quality Of Life

These same patients also completed a “dry eye-related quality of life score” test (DEQS), designed to measure the impact of bothersome eye symptoms themselves, as well as their impact on daily life.9 The lower the score the better, with a maximum total score of 60.

Both dosing groups had a total composite score (eye and daily life symptoms) of about 40 at the beginning of the study.4 Once treatment began, the scores fell rapidly in both groups.

In the group taking 30 mg per day, the score dropped to almost 22 after 30 days, but only dropped an additional 2 points by 60 days. The higher dose group saw continued improvement as time went on. In the group taking 60 mg per day, the score dropped to almost 27 after 30 days—and further dropped down to just 11 points after 60 days. That represents a 72% reduction (improvement) from baseline!

This supports the longer-lasting effects of the higher dosage seen on the test of tear production as well.

This human study documented dramatic enhancement in both tear fluid secretion and eye comfort using an oral extract preparation instead of eye drops. Maqui berry extract is a natural approach that is capable of changing the way the lacrimal glands function to boost tear fluid secretion and enhance the actual function of the tear film. Clinical results show lasting improvements in eye comfort.

But there’s evidence that you may be able to add still another layer of protection for your eyes, in the form ofomega-3 fatty acids, as we’ll now see.

The Perfect Pairing: Maqui Extract And Omega-3s

Omega-3 fatty acids are primarily known for their cardiovascular and neuroprotective benefits.38 But recent data show that supplementation with omega-3s can have a beneficial impact on dry eye syndrome by improving tear film breakup time and enhancing oily tear secretions (as measured by Schirmer’s test).39

“Tear film breakup time” is a term ophthalmologists use to indicate how rapidly the normally smooth tear layer disperses, leaving the eye exposed to dryness and potential injury.2,40,41 When the tear film breakup time is less than the rate of blinking, the eye suffers intermittent periods of exposure, leading to the symptoms of dry eye syndrome.

In a compelling study, patients with dry eye syndrome took a 500 mg dose (325 mg EPA and 175 mg DHA) of omega-3 fatty acids twice daily. After three months, the supplemented patients experienced a near 20-fold increase in tear film breakup time and a more than 4-fold improvement in symptom scores compared to placebo.41

These findings make perfect sense in light of the importance of the lipid layer secreted by the Meibomian glands, and suggests that pairing omega-3 supplementation with maqui berry extract would improve the overall tear layer composition by enhancing watery tear production (maqui extract) and improving the quality of the lipid layer (omega-3 fatty acids).

Summary

Dry eye syndrome is common, especially in older adults. Its effects can impact your mental and physical well-being.

The underlying issues involved in dry eye syndrome are simple: Too little watery tear production in the lacrimal glands means not enough water gets into your tears to fully moisten the eye surface, while too little oil production in the Meibomian glands means too much water evaporates from the eye surface, again leaving it exposed to damage.

These forces can change the very composition of your tears, leaving them over concentrated and incapable of properly lubricating the surface of your eyes.

Now a natural, orally-administered nutrient can soothe your eyes from the inside out by stimulating healthy tear production to restore your eye’s delicate ecosystem.

Extracts of the South American maqui berry have been found to boost tear fluid secretion and enhance the actual function of the tear film. For additional support, omega-3 fatty acids have been found to help slow tear evaporation from the eye.

Maqui berry extract represents an effective approach to restore comfort and composition of one’s tears and eye moisture.

If you have any questions on the scientific content of this article, please call a Life Extension® Health Advisor at 1-866-864-3027.

References

- Suchi ST, Gupta A, Srinivasan R. Contact allergic dermatitis and periocular depigmentation after using olapatidine eye drops. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2008 Sep-Oct;56(5):439-40.

- Gayton JL. Etiology, prevalence, and treatment of dry eye disease. Clin Ophthalmol. 2009;3:405-12.

- Tounaka K, Yuki K, Kouyama K, et al. Dry eye disease is associated with deterioration of mental health in male Japanese university staff. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2014;233(3):215-20.

- Le Q, Zhou X, Ge L, Wu L, Hong J, Xu J. Impact of dry eye syndrome on vision-related quality of life in a non-clinic-based general population. BMC Ophthalmol. 2012 Jul 16;12:22.

- Garcia-Resua C, Pena-Verdeal H, Remeseiro B, Giraldez MJ, Yebra-Pimentel E. Correlation between tear osmolarity and tear meniscus. Optom Vis Sci. 2014 Dec;91(12):1419-29.

- Yazici A, Sari ES, Sahin G, et al. Change in tear film characteristics in visual display terminal users. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2015 Feb 12;25(2):85-9.

- Schaumberg DA, Sullivan DA, Buring JE, Dana MR. Prevalence of dry eye syndrome among US women. Am J Ophthalmol. 2003 Aug;136(2):318-26.

- Asbell PA. Increasing importance of dry eye syndrome and the ideal artificial tear: consensus views from a roundtable discussion. Curr Med Res Opin. 2006 Nov;22(11):2149-57.

- Hitoe S, Tanaka J, Shimoda H. MaquiBright standardized maqui berry extract significantly increases tear fluid production and ameliorates dry eye-related symptoms in a clinical pilot trial. Panminerva Med. 2014 Sep;56(3 Suppl 1):1-6.

- Azuma M, Yabuta C, Fraunfelder FW, Shearer TR. Dry eye in LASIK patients. BMC Res Notes. 2014;7:420.

- Bron AJ, Tomlinson A, Foulks GN, et al. Rethinking dry eye disease: a perspective on clinical implications. Ocul Surf. 2014 Apr;12(2 Suppl):S1-31.

- Foulks GN. Pharmacological management of dry eye in the elderly patient. Drugs Aging. 2008;25(2):105-18.

- Galor A, Zheng DD, Arheart KL, et al. Dry eye medication use and expenditures: data from the medical expenditure panel survey 2001 to 2006. Cornea. 2012 Dec;31(12):1403-7.

- Cho YK, Archer B, Ambati BK. Dry eye predisposes to corneal neovascularization and lymphangiogenesis after corneal injury in a murine model. Cornea. 2014 Jun;33(6):621-7.

- Yagci A, Gurdal C. The role and treatment of inflammation in dry eye disease. Int Ophthalmol. 2014 Dec;34(6):1291-301.

- Batista TM, Tomiyoshi LM, Dias AC, et al. Age-dependent changes in rat lacrimal glands anti-oxidant and vesicular related protein expression profiles. Mol Vis. 2012;18:194-202.

- Horwath-Winter J, Schmut O, Haller Schober EM, Gruber A, Rieger G. Iodide iontophoresis as a treatment for dry eye syndrome. Br J Ophthalmol. 2005 Jan;89(1):40-4.

- Ding J, Sullivan DA. Aging and dry eye disease. Exp Gerontol. 2012 Jul;47(7):483-90.

- Nakamura S, Tanaka J, Imada T, Shimoda H, Tsubota K. Delphinidin 3,5-O-diglucoside, a constituent of the maqui berry (Aristotelia chilensis) anthocyanin, restores tear secretion in a rat dry eye model. J Funct Foods. 2014 Sep;10:346-54.

- Moon SW, Hwang JH, Chung SH, Nam KH. The impact of artificial tears containing hydroxypropyl guar on mucous layer. Cornea. 2010 Dec;29(12):1430-5.

- Benelli U. Systane lubricant eye drops in the management of ocular dryness. Clin Ophthalmol. 2011;5:783-90.

- Adams J, Wilcox MJ, Trousdale MD, Chien DS, Shimizu RW. Morphologic and physiologic effects of artificial tear formulations on corneal epithelial derived cells. Cornea. 1992 May;11(3):234-41.

- Available at: http://www.webmd.com/drugs/2/drug-76422/lubricant-eye-drops/details#side-effects. Accessed April 30, 2015.

- Abelson MB, Butrus SI, Weston JH, Rosner B. Tolerance and absence of rebound vasodilation following topical ocular decongestant usage. Ophthalmology. 1984 Nov;91(11):1364-7.

- Peyton SM, Joyce RG, Edrington TB. Soft contact lens and corneal changes associated with Visine use. J Am Optom Assoc. 1989 Mar;60(3):207-10.

- Soparkar CN, Wilhelmus KR, Koch DD, Wallace GW, Jones DB. Acute and chronic conjunctivitis due to over-the-counter ophthalmic decongestants. Arch Ophthalmol. 1997 Jan;115(1):34-8.

- Lev R, Clark RF. Visine overdose: case report of an adult with hemodynamic compromise. J Emerg Med. 1995 Sep-Oct;13(5):649-52.

- Ragam A, Kolomeyer AM, Kim JS, et al. Topical cyclosporine a 1% for the treatment of chronic ocular surface inflammation. Eye Contact Lens. 2014 Sep;40(5):283-8.

- Schnetler R, Gillan WDH, Koorsen G. Lipid composition of human meibum: a review. S Afr Optom. 2013;72(2): 86-93.

- Walcott B. The lacrimal gland and its veil of tears. News Physiol Sci. 1998 Apr;13:97-103.

- Benitez-Del-Castillo JM. How to promote and preserve eyelid health. Clin Ophthalmol. 2012;6:1689-98.

- Knop E, Knop N, Schirra F. Meibomian glands. Part II: physiology, characteristics, distribution and function of meibomian oil. Ophthalmologe. 2009 Oct;106(10):884-92.

- Available at: http://www.oryza.co.jp/html/english/pdf/Maqui%20berry_e%20Ver.1.0FFTK. Accessed May, 1, 2015.

- Available at: http://plantsforhumanhealth.ncsu.edu/healthy-living/cardiovascular-system/maqui-berry/. Accessed May 1, 2015.

- Suwalsky M, Vargas P, Avello M, Villena F, Sotomayor CP. Human erythrocytes are affected in vitro by flavonoids of Aristotelia chilensis (Maqui) leaves. Int J Pharm. 2008 Nov 3;363(1-2):85-90.

- Schreckinger ME, Wang J, Yousef G, Lila MA, Gonzalez de Mejia E. Antioxidant capacity and in vitro inhibition of adipogenesis and inflammation by phenolic extracts of Vaccinium floribundum and Aristotelia chilensis. J Agric Food Chem. 2010 Aug 25;58(16):8966-76.

- Tanaka J, Kadekaru T, Ogawa K, et al. Maqui berry (Aristotelia chilensis) and the constituent delphinidin glycoside inhibit photoreceptor cell death induced by visible light. Food Chem. 2013 Aug 15;139(1-4):129-37.

- Swanson D, Block R, Mousa SA. Omega-3 fatty acids EPA and DHA: health benefits throughout life. Adv Nutr. 2012 Jan;3(1):1-7.

- Liu A, Ji J. Omega-3 essential fatty acids therapy for dry eye syndrome: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled studies. Med Sci Monit. 2014;20:1583-9.

- Su TY, Chang SW, Yang CJ, Chiang HK. Direct observation and validation of fluorescein tear film break-up patterns by using a dual thermal-fluorescent imaging system. Biomed Opt Express. 2014 Jul 14;5(8):2614-9.

- Bhargava R, Kumar P, Kumar M, Mehra N, Mishra A. A randomized controlled trial of omega-3 fatty acids in dry eye syndrome. Int J Ophthalmol. 2013;6(6):811-6.

- Cursiefen C, Hofmann-Rummelt C, Küchle M, Schlötzer-Schrehardt U. Pericyte recruitment in human corneal angiogenesis: an ultrastructural study with clinicopathological correlation. Br J Ophthalmol. 2003 Jan;87(1):101-6.

- Stewart JM, Lee OT, Wong FF, Schultz DS, Lamy R. Cross-linking with ultraviolet-a and riboflavin reduces corneal permeability. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011 Nov 29;52(12):9275-8.

- Available at: http://www.visionrx.com/library/enc/enc_cornea.asp. Accessed May 1, 2015.

- Cejka C, Cejkova J. Oxidative stress to the cornea, changes in corneal optical properties, and advances in treatment of corneal oxidative injuries. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2015;2015:591530.

- Nakamura S, Kinoshita S, Yokoi N, et al. Lacrimal hypofunction as a new mechanism of dry eye in visual display terminal users. PLoS One. 2010;5(6):e11119.

- Wong J, Lan W, Ong LM, Tong L. Non-hormonal systemic medications and dry eye. Ocul Surf. 2011 Oct;9(4):212-26.

- Fujita M, Igarashi T, Kurai T, Sakane M, Yoshino S, Takahashi H. Correlation between dry eye and rheumatoid arthritis activity. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005 Nov;140(5):808-13.

- Javadi MA, Feizi S. Dry eye syndrome. J Ophthalmic Vis Res. 2011 Jul;6(3):192-8.

- Akpek EK, Lindsley KB, Adyanthaya RS, Swamy R, Baer AN, McDonnell PJ. Treatment of Sjögren’s syndrome-associated dry eye an evidence-based review. Ophthalmology. 2011 Jul;118(7):1242-52.

- Ousler GW, Wilcox KA, Gupta G, Abelson MB. An evaluation of the ocular drying effects of 2 systemic antihistamines: loratadine and cetirizine hydrochloride. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2004 Nov;93(5):460-4.

- Iskeleli G, Karakoc Y, Ozkok A, Arici C, Ozcan O, Ipcioglu O. Comparison of the effects of first and second generation silicone hydrogel contact lens wear on tear film osmolarity. Int J Ophthalmol. 2013;6(5):666-70.

- McMonnies CW. How blink anomalies can contribute to post-lasik neurotrophic epitheliopathy. Optom Vis Sci. 2015 Mar 30.

- Portello JK, Rosenfield M, Chu CA. Blink rate, incomplete blinks and computer vision syndrome. Optom Vis Sci. 2013 May;90(5):482-7.

- McCulley JP, Uchiyama E, Aronowicz JD, Butovich IA. Impact of evaporation on aqueous tear loss. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 2006;104:121-8.

- Available at: http://www.hopkinssjogrens.org/disease-information/diagnosis-sjogrens-syndrome/schirmers-test/. Accessed May 1, 2015.

- Available at: http://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/ency/article/003501.htm. Accessed May 1, 2015.