Still, there is overwhelming evidence that crumb rubber or recycled rubber that is used in thousands of sports fields, including now our beloved Heights School’s new turf field, is full of chemical that may puts kids and their parents at an increased risk of cancer– in my opinion: this is not a hard fact but a statement of logic from the evidence coming out from many publications.

The first time I was on a turf field was 2 summers ago. The smell in the heat was overwhelmingly horrid. “How could this be healthy for kids?” I thought. Thus began a study looking into this. I even tried to convince our school to not go Turf.

So what are the risks:

The key issues are the polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) and the many other carcinogenic compounds in these recycled rubbers.

People smell these noxious compounds most especially in the summer.

Here are good reviews below.

For now, I recommend for my kids:

1. Never touch the turf with bare skin.

2. Always wear shoes when on turf and socks.

3. Avoid playing in the hot sun on turf fields

4. Do not lay on these fields even on a blanket.

5. Always choose natural grass over turf until studies prove without a doubt there is no increased cancer risk.

6. Never swim in “the pit” at the Heights as the run off of the turf field is likely bad news as well.

SLC

Environmental Research

Volume 160, January 2018, Pages 256-268

Comprehensive multipathway risk assessment of chemicals associated with recycled (“crumb”) rubber in synthetic turf fields

Determination of priority and other hazardous substances in football fields of synthetic turf by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry: A health and environmental concern.

Author information

- 1

- Laboratory of Research and Development of Analytical Solutions (LIDSA), Department of Analytical Chemistry, Nutrition and Food Science, Faculty of Chemistry, E-15782, Campus Vida, Universidade de Santiago de Compostela, Santiago de Compostela, Spain.

- 2

- Agronomic and Agrarian Research Centre (INGACAL-CIAM), Unit of Organic Contaminants, Apartado 10, 15080, A Coruña, Spain.

- 3

- Laboratory of Research and Development of Analytical Solutions (LIDSA), Department of Analytical Chemistry, Nutrition and Food Science, Faculty of Chemistry, E-15782, Campus Vida, Universidade de Santiago de Compostela, Santiago de Compostela, Spain. Electronic address: maria.llompart@usc.es.

Abstract

Release of particles, organic compounds, and metals from crumb rubber used in synthetic turf under chemical and physical stress.

Abstract

Exposure to aged crumb rubber reduces survival time during a stress test in earthworms (Eisenia fetida).

Abstract

Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs)

What Health Effects Are Associated With PAH Exposure?

CE Original Date: July 1, 2009

CE Renewal Date: July 1, 2011

CE Expiration Date: July 1, 2013

Download Printer-Friendly version

| Previous Section | Next Section |

Learning Objectives |

Upon completion of this section, you will be able to

|

||||||||||||||||||

Introduction |

The most significant endpoint of PAH toxicity is cancer.

PAHs generally have a low degree of acute toxicity to humans. Some studies have shown noncarcinogenic effects that are based on PAH exposure dose [Gupta et al. 1991].

After chronic exposure, the non-carcinogenic effects of PAHs involve primarily the

Many PAHs are only slightly mutagenic or even nonmutagenic in vitro; however, their metabolites or derivatives can be potent mutagens.

|

||||||||||||||||||

Carcinogenicity |

The carcinogenicity of certain PAHs is well established in laboratory animals. Researchers have reported increased incidences of skin, lung, bladder, liver, and stomach cancers, as well as injection-site sarcomas, in animals. Animal studies show that certain PAHs also can affect the hematopoietic and immune systems and can produce reproductive, neurologic, and developmental effects [Blanton 1986, 1988; Dasgupta and Lahiri 1992; Hahon and Booth 1986; Malmgren et al. 1952; Philips et al. 1973; Szczeklik et al. 1994; Yasuhira 1964; Zhao 1990].

It is difficult to ascribe observed health effects in epidemiological studies to specific PAHs because most exposures are to PAH mixtures.

Increased incidences of lung, skin, and bladder cancers are associated with occupational exposure to PAHs. Epidemiologic reports of PAH-exposed workers have noted increased incidences of skin, lung, bladder, and gastrointestinal cancers. These reports, however, provide only qualitative evidence of the carcinogenic potential of PAHs in humans because of the presence of multiple PAH compounds and other suspected carcinogens. Some of these reports also indicate the lack of quantitative monitoring data [Hammond et al. 1976; Lloyd 1971; Mazumdar 1975; Redmond et al. 1972; Redmond and Strobino 1976].

The earliest human PAH-related epidemiologic study was reported in 1936 by investigators in Japan and England who studied lung cancer mortality among workers in coal carbonization and gasification processes. Subsequent U.S. studies among coke oven workers confirmed an excess of lung cancer mortality, with the suggestion of excessive genitourinary system cancer mortality. Later experimental studies showed that PAHs in soot were probably responsible for the increased incidence of scrotal cancer noted by Percival Pott among London chimney sweeps in his 1775 treatise [Zedeck 1980].

|

||||||||||||||||||

Research |

Continued research regarding the mutagenic and carcinogenic effects from chronic exposure to PAHs and metabolites is needed. The following table indicates the carcinogenic classifications of selected PAHs by specific agencies.

|

||||||||||||||||||

Key Points |

Good Review:

Synthetic Turf Fields, Crumb Rubber, and Alleged Cancer Risk

Current Opinion

First Online: 11 May 2017

Abstract

Most synthetic turf fields have crumb rubber interspersed among the simulated grass fibers to reduce athletic injuries by allowing users to turn and slide more readily as they play sports or exercise on the fields. Recently, the crumbs have been implicated in causing cancer in adolescents and young adults who use the fields, particularly lymphoma and primarily in soccer goalkeepers. This concern has led to the initiation of large-scale studies by local and federal governments that are expected to take years to complete. Meanwhile, should the existing synthetic turf fields with crumb rubber be avoided? What should parents, players, coaches, school administrators, and playground developers do? What should sports medicine specialists and other health professionals recommend? Use grass fields when weather and field conditions permit? Exercise indoors? Three basic premises regarding the nature of the reported cancers, the latency of exposure to environmental causes of cancer to the development of clinically detectable cancer, and the rarity of environmental causation of cancer in children, adolescents, and young adults suggest otherwise.

Download article PDF

Key Points1 Background

A hypothesis that synthetic turf fields can cause cancer was publicized after a soccer coach at the University of Washington collected a list of young adult soccer players, particularly goalkeepers, who had been diagnosed with lymphoma and other cancers [1]. Because crumb rubber infill, the shock absorption layer within synthetic turf derived from recycled automotive tires, contains some potentially carcinogenic chemicals, the turf has been implicated. As goalkeepers are more likely than outfield players to ingest or inhale the crumb or absorb crumb constituents via their skin, the hypothesis gained credence. As a result, some school systems and park departments have abandoned plans to install synthetic turf fields, and some states have introduced bills to ban such installations [2]. In 2015, the California Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment began an Environmental Health Study of Synthetic Turf, and in early 2016, three US federal agencies launched the Federal Research Action Plan on Recycled Tire Crumb Used on Playing Fields [3, 4, 5]. Millions of dollars have been earmarked for these studies [6] that are expected to take years to complete.

2 State of Science

Several studies of human cancer and/or non-cancer risk using data from direct measurements or data reported in the literature have been reported [7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14]. Other studies have focused directly or indirectly on the toxicity of one or more constituents of crumb rubber [14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23]. None of these studies have identified a significant human carcinogenic risk from exposure to crumb rubber at synthetic turf fields. Menichini and co-investigators [22] estimated that 0.4 ng/m3 of benzo(a)pyrene at an indoor facility had a potential for an excess lifetime cancer risk of 1 in a million athletes after an intense 30-year activity level. Marsili and coauthors [24] considered the hazard indices and cumulative excess risk values for cancer to be below levels of concern for measured chemicals; they reasoned that polycyclic aromatic amines in the crumb rubber could potentially increase cancer risk after long-term frequent exposures at fields under very hot conditions (60 °C). Polycyclic aromatic amines have been implicated in some studies as an occupational lymphomagen, but the most recent systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies refuted the association [25]. Kim and colleagues [18] proposed a potential risk for children with pica behavior through ingestion of crumb rubber material at playgrounds. The most recent review published in a peer-reviewed journal concluded that users of artificial turf fields, even professional athletes, are not exposed to elevated risks [26]. Since this review, the most detailed studies of potential carcinogenicity conducted to date, by the Washington State Department of Health in USA and the Dutch National Institute for Public Health and the Environment, did not find an association between the fields and an increased incidence of cancer in the susceptible age group [27, 28].

Meanwhile, what should parents, players, coaches, school administrators, and playground developers do and physicians recommend? Avoid synthetic turf fields and use grass fields when weather and field conditions permit? Three basic premises suggest otherwise.

2.1 The Cancers Cited in Media Reports About Soccer Players are Precisely those Cancers that are Expected to Occur in the Age Group of Concern

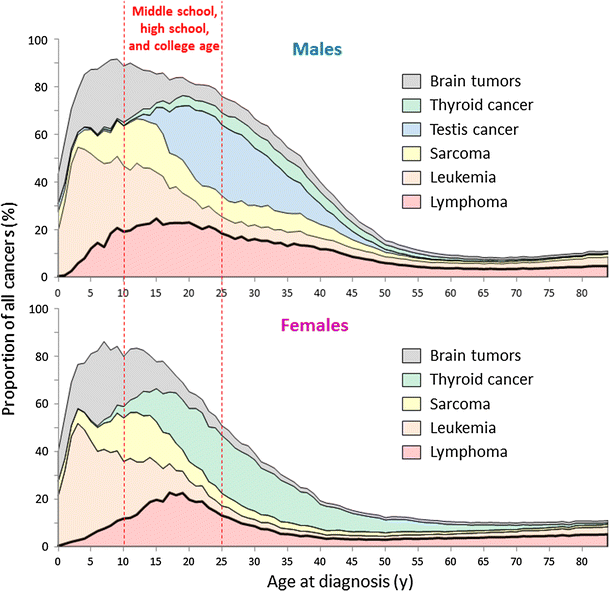

Not only is lymphoma the most common cancer in high-school and college-age persons, the other cases in the reported cohort—leukemia, sarcoma, testis cancer, thyroid cancer, and brain tumors—are the next most common cancers in the age group. Together with lymphoma, these cancers account for 80–90% of the cancers in male individuals of middle-school, high-school, and college age and 50–80% of female individuals in the age group (Fig. 1) [29]. In other words, the suspect cancers are precisely those expected without having to invoke exogenous factors.

Fig. 1

Prevalence of the suspect cancers of all cancers by age and sex.

Source: US National Cancer Institute Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program, SEER 18 Regions, 2000–2013 [29]

The issue then is whether the absolute frequency is more than expected. An ecologic investigation applied to the state with the largest number of synthetic fields, California, and to 17 other regions of USA, did not indicate that the incidence is greater in counties and regions with synthetic fields or that the incidence is proportional to the prevalence of such fields when race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status of those who have access to synthetic fields are included in the analyses [30]. The method used did not, however, directly measure the incidence in soccer players per se and could miss an increase of lymphoma in them, particularly if only a small percentage of cases have exposure to synthetic turf fields. In the State of Washington, about 25% of 15-year-old individuals have been estimated to play soccer at some point in their lives [27]. The proportion is likely to be higher in California, given the more conducive weather and the greater Hispanic population. If so, the ecologically derived data are more meaningful in assessing the risk than the face value of the results. A more complete ecologic study of all 58 counties in California is in progress.

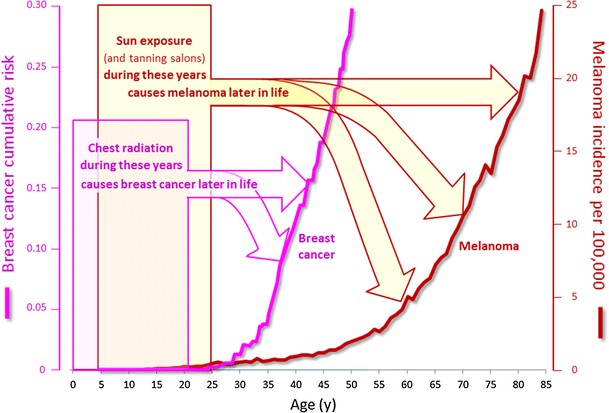

2.2 Exposure to Environmental Causes of Cancer During Childhood, Adolescence, and Early Adulthood Results in Cancer Later in Life

Figure 2 shows two established causes of cancer resulting from exposures during childhood and adolescent: melanoma after ultraviolet radiation and breast cancer after chest radiation. The type of melanoma caused by ultraviolet rays is rarely diagnosed before the age of 35 years (Fig. 2, brown curve) and breast cancer caused by chest radiation for cancer has a median latency of 14 years [31]and rarely occurs before 30 years of age (Fig. 2, pink curve). When melanoma occurs in younger persons, it is nearly always not related to external exposure. If crumb rubber causes cancer in young athletes, it would be expected to become clinically detectable at an older age than during adolescence or early adult years.

Fig. 2

Incidence of melanoma in sun-exposed areas of skin (face, lips, ears) and, in female individuals, breast cancer after chest radiation during childhood or adolescence, and latency to clinical manifestation.

2.3 Environmental Causation of Cancer in Children, Adolescents, and Young Adults is Rare

During the 1990s, the world’s largest pediatric cancer research organization, the Children’s Cancer Group, was awarded millions of dollars of research grants to determine what caused cancer in the young. None of those studies, nationally and in multistate surveys, within homes and with environmental sampling, of childhood and prenatal exposures, and a host other variables, uncovered evidence for an environmental factor that “might explain more than a small fraction of the observed cases” [32]. The conclusion was that, with few exceptions, cancer during childhood, adolescence, and early adulthood is a mistake of nature—spontaneous mutation to malignancy—and not the result of exogenous causes [33].

3 Conclusion

All the prior studies and the perspectives expressed here cannot completely exculpate crumb rubber as a cause of cancer. Even the Washington State study of the very soccer players whose cancer raised the concern is not without significant limitations, as fully expressed by the investigators [27] and critiqued by others [34]. The concern of parents, coaches, school administrators, sports medicine specialists, other healthcare professionals, and the players themselves is reasonable, especially when, if the hypothesis were true, the adverse outcome is potentially preventable. After all, cancer is one of the most feared diseases [35] and to have it happen in the young could not be worse.

It is also human nature to blame. Blaming autism on vaccines is a recurrent quintessential example. It also illustrates another human behavior: refusal to believe objective scientific irrefutable evidence [36] and this anti-science attitude appears to be increasing in our society [37, 38]. This human need and attendant denial causes unnecessary alarm, especially when cancer is the fear and especially in the United States. When American adults were asked which of five major diseases they were most afraid, 41% said cancer, 31% said Alzheimer’s disease and only 6-8% named heart disease, stroke or diabetes [39].

Regular physical activity during adolescence and early adulthood helps prevent cancer later in life [40]. Restricting the use or availability of all-weather year-round synthetic fields and thereby potentially reducing exercise could, in the long run, actually increase cancer incidence, as well as cardiovascular disease and other chronic illnesses [41]. That the Washington State study found a much lower incidence of cancer in their soccer players than expected from their general population [27] supports the concern that restricting access to such fields and playgrounds may lead to the opposite of what was intended.

|