GPC usually due to contact lens overuse. Vernal (VKC): or Spring catarrh is a seasonal allergic disorder; both mediated by IgE and can look similar under microscope.

Giant papillary conjunctivitis is a common complication of contact lens wear. It has also been called contact lens–induced papillary conjunctivitis (CLPC). Spring first described giant papillary conjunctivitis in association with contact lens use.[1]Allergic symptoms accompany papillary changes in the ocular tarsal palpebral conjunctivae as part of an immunoglobulin E (IgE)–mediated hypersensitivity reaction.[2, 3, 4] (See Etiology, History, and Physical Examination .)

Treatments for GPC: stop CL, try cold artificial tears. If does not help, we try steroid, and/or Restasis. Then try other CL material when quiet.

Great references below:

1. Wilkipedia:

Vernal keratoconjunctivitis (VKC) or Spring catarrh is a recurrent, bilateral, and self-limiting inflammation of conjunctiva, having a periodic seasonal incidence.

Contents

[hide]

Etiology[edit]

VKC is thought to be an allergic disorder in which IgE mediated mechanism play a role. Such patients often give family history of other atopic diseases such as hay fever, asthma or eczema, and their peripheral blood shows eosinophilia and increased serum IgE levels.

Predisposing factors[edit]

- Age and sex – 4–20 years; more common in boys than girls.

- Season – More common in summer. Hence, the name Spring catarrh is a misnomer. Recently it is being labelled as Warm weather conjunctivitis.

- Climate – More prevalent in the tropics. VKC cases are mostly seen in hot months of summer, therefore, more suitable term for this condition is “summer catarrh” Ref.[1]

Pathology[edit]

- Conjunctival epithelium undergoes hyperplasia and sends downward projection into sub-epithelial tissue.

- Adenoid layer shows marked cellular infiltration by eosinophils, lymphocytes, plasma cells and histiocytes.

- Fibrous layer show proliferation which later undergoes hyaline changes.

- Conjunctival vessels also show proliferation, increased permeability and vasodilation.

Clinical picture[edit]

- Symptoms- VKC is characterised by marked burning and itchy sensations which may be intolerable and accentuates when patient comes in a warm humid atmosphere. Associated symptoms include mild photophobia, lacrimation, stringy discharge and heaviness of eyelids.[citation needed]

- Signs of VKC can be described in three clinical forms.

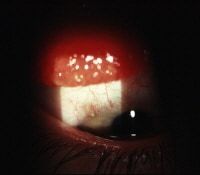

- Palpebral form- Usually upper tarsal conjunctiva of both the eyes is involved. Typical lesion is characterized by the presence of hard, flat-topped papillae arranged in cobblestone or pavement stone fashion. In severe cases papillae undergo hypertrophy to produce cauliflower-like excrescences of ‘giant papillae’.

- Bulbar form- It is characterised by dusky red triangular congestion of bulbar conjunctiva in palpebral area, gelatinous thickened accumulation of tissue around limbus and presence of discrete whitish raised dots along the limbus (Tranta’s spots).

- Mixed form- Shows the features of both palpebral and bulbar types.

Vernal keratopathy[edit]

Corneal involvement in VKC may be primary or secondary due to extension of limbal lesions. Vernal keratopathy includes 5 types of lesions.[citation needed]

- Punctuate epithelial keratitis.

- Ulcerative vernal keratitis.

- Vernal corneal plaques.

- Subepithelial scarring.

- Pseudogerontoxon.

Treatment[edit]

- Local therapy- Topical steroids are effective. Commonly used solutions are of fluorometholone, medrysone, betamethasone or dexamethasone. Mast cell stabilizers such as sodium cromoglycate (2%) drops 4–5 times a day are quite effective in controlling VKC, especially atopic ones. Azelastine eyedrops are also effective. Topical antihistamines can be used. Acetyl cysteine (.0.5%) used topically has mucolytic properties and is useful in the treatment of early plaque formation. Topical Cyclosporine is reserved for unresponsive cases.[citation needed]

- Systemic therapy- Oral antihistamines and oral steroids for severe cases.

- Treatment of large papillae- Cryo application, surgical excision or supratarsal application of long-acting steroids.

- General measures include use of dark goggles to prevent photophobia, cold compresses and ice pack for soothing effects, change of place from hot to cold areas.

- Desensitization has also been tried without much rewarding results.

- Treatment of vernal keratopathy- Punctuate epithelial keratitis require no extra treatment except that instillation of steroids should be increased. Large vernal plaque requires surgical excision. Ulcerative vernal keratitis require surgical treatment in the form of debridement, superficial keratectomy, excimer laser therapeutic keratectomy, as well as amniotic membrane transplantation to enhance re-epithelialisation.

- PROSE (prosthetic replacement of the ocular surface ecosystem) treatment, an iterative medical process that uses custom designed and fabricated prosthetic devices, maintains ocular surface health and improves vision in individuals with VKC.[2]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ Shah, Syed Imtiaz Ali (2014). Concise Ophthalmology (4th ed.). Paramount. p. 31. ISBN 978-969-637-001-7.

- ^ Rathi VM, Sudharman Mandathara P, Vaddavalli PK, Dumpati S, Chakrabarti T, Sangwan VS (May 2012). “Fluid-filled scleral contact lenses in vernal keratoconjunctivitis”. Eye & Contact Lens 38 (3): 203–6.doi:10.1097/ICL.0b013e3182482eb5. PMID 22367220.

2. From Medscape:

Prior to the popularization of hydrogel (soft) contact lenses over the past 4 decades, such reactions were primarily seen as allergic conjunctivitis (AC) or vernal keratoconjunctivitis (VKC). VKC is a seasonal, atopic disease in young people (more common in boys) that occasionally becomes severe and leads to shield corneal ulcers and other complications. Giant papillary conjunctivitis related to contact lens wear never leads to the severe tissue morbidity of VKC. (See Prognosis.)

Giant papillary conjunctivitis symptoms and signs, such as papillary changes in the tarsal conjunctiva, have been associated with the use of all types of contact lenses (eg, rigid, hydrogel, silicone hydrogel, piggyback,[5] scleral, prosthetic). (See History and Physical Examination.)

Similar reactions have been noted with ocular prostheses, extruding scleral buckles, exposed ocular sutures, and even elevated corneal scars. The initially small papillae eventually coalesce with expanding internal collections of inflammatory cells. When the lesions reach a diameter of more than 0.3 mm, often approaching or exceeding 1 mm, the condition is referred to as giant papillary conjunctivitis. Images of eyelid papillae appear below. (See Etiology.)

Very large papillae in the everted upper lid of a patient who wears hydrogel (soft) contact lenses.

Very large papillae in the everted upper lid of a patient who wears hydrogel (soft) contact lenses. Giant papillary conjunctivitis (GPC) response (slightly out of focus) seen in the upper lid of a young patient recovering from cataract extraction with an exposed suture barb (in focus).

Giant papillary conjunctivitis (GPC) response (slightly out of focus) seen in the upper lid of a young patient recovering from cataract extraction with an exposed suture barb (in focus).

Because of the high prevalence of giant papillary conjunctivitis in contact lens wearers, every patient who wears contact lenses should be considered as a potential patient with giant papillary conjunctivitis.

See the following for more information:

History

Patients with giant papillary conjunctivitis (GPC) often report an increase in contact lens soilage, ocular itching, and mucous discharge in tears, as well as blurred vision and conjunctival injection. This can be accompanied by decreased contact lens tolerance and mechanical stability.

Distinguish giant papillary conjunctivitis from the following conditions:

-

Other diseases that cause conjunctivitis and ocular itching/mucus – Typically ocular allergies (hay fever conjunctivitis) but also viral and bacterial conjunctivitis and blepharitis

-

Other diseases that cause papillary changes in the tarsal conjunctiva of the lids, especially vernal andatopic conjunctivitis

-

Other giant papillary-forming disorders by the creamy white appearance of the giant papillae center/top

-

Other diseases that cause follicular changes, which can easily be confused with papillary changes, in the palpebral conjunctivae of the lids –Viral conjunctivitis (adenovirus and herpes), chlamydial infections, and Gel-Coombs type IV hypersensitivity and toxic reactions, particularly to contact lens solutions

-

Other causes of contact lens intolerance, such as poor fit, dry eyes, and blepharitis

Differential Diagnoses

Histologic Findings

Quantitative histologic findings with either VKC or giant papillary conjunctivitis suggest multiple abnormalities.

Neutrophils and lymphocytes are usually present only in the conjunctival epithelium and substantia propria, whereas both mast cells and plasma cells are present in the substantia propria but not the epithelium. Basophils and eosinophils are not usually found in either tissue. However, in giant papillary conjunctivitis, degranulating mast cells are found in the epithelium, and both eosinophils and basophils are found in the epithelium and substantia propria. The predominant normal skin (and small intestine) subtype of mast cell, or mast cell with both tryptase and chymase (MCtc), is found in patients with giant papillary conjunctivitis, whereas the mast cell subtype with only tryptase (MCt), which is usually the predominant subtype of mast cell in the lung, is found in the substantial propria of the conjunctiva in VKC.[11] Also, MCt depends on T lymphocytes, whereas MCtc does not.

Although the density of inflammatory cells may not change much between healthy patients and patients with giant papillary conjunctivitis, the increase in tissue mass due to the disease means that the number of inflammatory cells doubles.[12]

Common tear abnormalities found in giant papillary conjunctivitis include elevated levels of histamine,[13] immunoglobulin G (IgG), IgE, and immunoglobulin M (IgM),[14] as well as complement factors, such as C3, factor B, and C3 anaphylatoxin.[15]

Decay-accelerating factor, which inhibits C3 amplification in the complement cascade, is decreased in patients with giant papillary conjunctivitis,[16] whereas lactoferrin (also present in VKC) is increased,[17, 18] as is neutrophilic chemotactic factor,[19] leukotriene,[20] and eotaxin, a chemokine that attracts eosinophils.[21]

Zhong et al also found that the membranous epithelial cells (M cells) that participate in the binding, uptake, and translocation of antigens in mucosa associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) overproliferate during the course of this disease and, in addition to increased lymphocytes, give rise to the conjunctival changes in giant papillary conjunctivitis.[22]

These multiple changes, regardless of whether the initiating insult is mechanical or immunologic, document the substantial inflammatory activities that result in the clinical picture of contact lens–associated giant papillary conjunctivitis.

Approach Considerations

Topical steroids can be used in the treatment of giant papillary conjunctivitis but are not necessary in all cases. Contact lens hygiene is an important component in the disease’s deterrence.

Medication Summary

Pharmacologic management is a mildly to moderately effective, adjunctive treatment when patients with giant papillary conjunctivitis cannot or will not discontinue wearing contact lenses. Giant papillary conjunctivitis is a Gel-Coombs type 1 disease with degranulated conjunctival mast cells as the chief histologic feature; therefore, drugs that inhibit mast cell degranulation are effective.[26]

The most commonly used topical medications are combination, dual-acting H1 receptor antagonists and inhibitors of histamine release from mast cells (ie, olopatadine hydrochloride, ketotifen fumarate). Topical mast cell stabilizers, NSAIDs, and antihistamines are also used. Steroids can be useful for severe cases.[23, 24]

Topical ophthalmic medications should be used cautiously with contact lens wear, because these medications are commonly preserved with benzalkonium chloride (BAK). BAK is associated with corneal epithelial toxicity episodes (a greater concern with hydrogel contact lenses).

If medication must be administered concomitantly with hydrogel contact lenses, application should be restricted to a maximum of 3 times a day (ie, 1 gtt just prior to contact lens wear, 1 gtt immediately upon contact lens removal, 1 gtt hs). Once-daily and twice-daily ophthalmic medications are now available (eg, Pataday, Zaditor, Elestat, Lastacaft) for increased patient compliance and convenience, especially for contact lens wearers. Patients should wait at least 10 minutes after medication instillation before contact lens insertion.