Why Do My Eyelids Twitch?

It is called Eyelid Myokymia

Recently, a patient asked me about her teenager who started having eyelid twitching in both eyes after she had passed out and hit her head. The parents had not noted it before but now notice it quite often. It involves just her upper eyelids and not his cheeks, rest of face, or jaw. The daughter does not notice when her eyelids twitch (which would indicate it is not blepharospasm: see below), and parents notice that it may be worse after school or track. She did not have a CT scan or MRI after she had passed out. Her pediatrician feels that episode was due to dehydration after a track meet. Her neurologic exam was normal and she had normal pupils with no afferent pupillary defect. What would you do to help this young woman?

Eye twitching, eyelid tics and spasms are common and called Eyelid Myokymia in most cases unless it is repetitive, unremitting (ie, is there most of the time) and involves the full closure of the eyelids, in which case it is called Blepharospasm.

This is Eyelid Myokymia:

This is Eyelid Myokymia:

Here is a video on Blepharospasm. It can involve just one eye/side but more commonly involves both.

It can be disconcerting to feel or see a loved on with this condition, but in most cases it will resolve with treatments for the underlying cause.

For my friend’s son, it is likely due to dehydration, excessive exercise, and general physical stress. All this most likely caused the passing out episode. And it is possible the mild head trauma he might of sustained when he passed out, made the 7th Cranial Nerve begin to fire more frequently. If the twitching continues, he may need a full work up for the syncopal episode (ie the passing out), especially if he is dizzy, has any headaches, or feels like he is going to pass out again: a full cardiac (heart) work up is needed and an MRI with contrast of brain and Cranial Nerve 7 pathway.

Time will tell if it is truly just Eyelid Myokymia. These are the 10 most common causes is the cause.

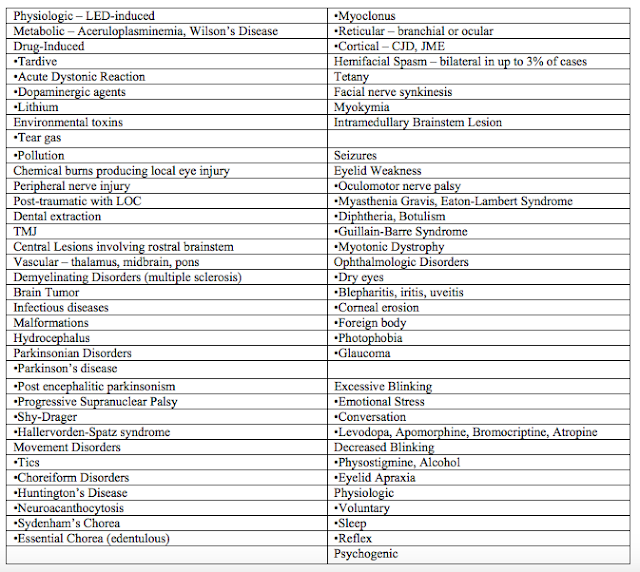

For a full list of potential causes, see Chart 1 below. This is what is going through your MD’s mind when they see this, but thankfully most are not common.

10 Most Common Causes of Involuntary Eyelid Twitching and/or Eyelid Closing

1. Stress

2. Lack of Sleep

3. Eye Strain: get vision checked

4. Caffeine: avoid for a week & see if goes away.

5. Dry Eyes: use warm compresses 2-3 times/day to help produce a stable tear film. Use artificial tears 4x per day to see if symptoms go away.

6. Dehydration: be sure to always be drinking 10 glasses of water per day: that is 64 oz of water at least–more if you are exercising.

7. Excess Physical Exertion: see if taking a break from exercise helps.

8. Nutritional imbalances: be sure you are eating enough Magnesium. Take a multivitamin per day.

9. Allergies: see eyeMD or allergist for simple, non-painful allergy test if above has not helped.

10. Medication side effects: check all medication inserts if taking any pills by mouth.

11. Alcohol: avoid if taking

12. Tobacco: avoid as it is a stimulant

13. Previous Head Trauma: rare so be sure a full neurological exam has been done.

Chart 1: Conditions Associated with Involuntary Eyelid Twitching and/or Eyelid Closing

Treatment for Eyelid Twitching:

1. The twitching most often goes away so be reassured and try to reduce and reduce precipitating factors, if identifiable, are appropriate for many patients.

2. Drink less caffeine. Avoid alcohol till resolved.

3. Get adequate sleep.

4. Get full eye exam & keep your eye surfaces and membranes lubricated with over-the-counter artificial tears or eye drops.

5. Apply a warm compress to your eyes when a spasm begins.

6. De-stress: prayer and meditate if happens when you are stressed.

7. If symptoms persist or are severe, local subcutaneous botulinum toxin A (BOTOX®) injections of 2.5-5 units each to the affected eyelid region provide relief for 12-18 weeks. If the upper eyelid is involved, the injections should not be placed near the levator palpebrae; otherwise, ptosis (lid droop) lasting weeks will result.

Adverse effects include temporary lid laxity, which may produce lagophthalmus, exposure keratopathy, and ptosis.

The efficacy of other agents has not been proven.

Prognosis

Prognosis is excellent in most cases.

Sandra Lora Cremers, MD, FACS

If the twitching continues despite trying the above, more information below:

When your eyelid is twitching, you may feel that everyone else can see it, but most eyelid twitches are subtle and not easily seen by others. If others are noticing it, it could be Blepharospasm.

The difference between Eyelid Myokymia and Blepharospasm is that Eyelid Myokymia is usually mild twiching and usually involves one eyelid at a time. It usually resolves with treatment or removing offending cause (as noted above and expanded below). Blepharospasm is a more complete muscular contraction with full closure of the eye. It can be harder to treat and thus last longer. More patients need Botox injection (see below) with true Blepharospasm compared to Eyelid Myokymia.

From: http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1213160-overview

Myokymia is characterized by spontaneous, fine fascicular contractions of muscle without muscular atrophy or weakness. Eyelid myokymia results from fascicular contractions of the orbicularis oculi muscle. Eyelid myokymia is typically unilateral, with the most common involvement being one of the lower eyelids. When multiple eyelids are involved, the fascicular contractions of each eyelid are independent of each other.

In most cases, eyelid myokymia is benign, self-limited, and not associated with any disease. Intervention is usually unnecessary. Rarely, eyelid myokymia may occur as a precursor of hemifacial spasm, blepharospasm, Meige syndrome, spastic-paretic facial contracture, and multiple sclerosis.

Patients with eyelid myokymia usually note sporadic “jumping” or “twitching” of one of the lower eyelids. Eyelid myokymia may also involve one of the upper eyelids or multiple eyelids. The irregular contractions are usually unilateral and may occur intermittently for days to months.

In rare cases, the contractions may be severe enough to move the eye to produce oscillopsia.

A history of stress, fatigue, and excessive caffeine or alcohol intake may be present. The use of topiramate in migraineurs has been questioned as a cause of eyelid myokymia.

Usually a few lifestyle-related questions can help determine the likely cause of eye twitching and the best way to get it to stop.

Stress. While we’re all under stress at times, our bodies react in different ways. A twitching eye can be one sign of stress, especially when it is related to vision problems such as eye strain (see below).

Yoga, breathing exercises, spending time with friends or pets and getting more down time into your schedule are among the many ways to reduce stress that may be causing the twitch.

Tiredness. A lack of sleep, whether because of stress or some other reason, can trigger a twitching eyelid. Catching up on your sleep can help.

Eye strain. Vision-related stress can occur if, for instance, you need glasses or a change of glasses. Even minor vision problems can make your eyes work too hard, triggering eyelid twitching. Schedule an eye exam and have your vision checked and your eyeglass prescription updated.

Computer eye strain from overuse of computers, tablets and smartphones also is a common cause of eyelid twitching. Follow the “20-20-20 rule” when using digital devices: Every 20 minutes, look away from your screen and allow your eyes to focus on a distant object (at least 20 feet away) for 20 seconds or longer. This reduces eye muscle fatigue that may trigger eyelid twitching.

If you spend a lot of time on the computer, you might want to talk to your eye doctor about special computer eyeglasses.

Caffeine. Too much caffeine can trigger eye twitching. Try cutting back on coffee, tea, chocolate and soft drinks (or switch to decaffeinated versions) for a week or two and see if your eye twitching disappears.

Alcohol. Try abstaining for a while, since alcohol also can cause eyelids to twitch.

Dry eyes. Many adults experience dry eyes, especially after age 50. Dry eyes are also very common among people who use computers, take certain medications (antihistamines, antidepressants, etc.), wear contact lenses and consume caffeine and/or alcohol. If you are tired and under stress, this too can increase your risk of dry eyes.

If you have a twitching eyelid and your eyes feel gritty or dry, see your eye doctor for a dry eye evaluation. Restoring moisture to the surface of your eye may stop the spasm and decrease the risk of twitching in the future.

Nutritional imbalances. Some reports suggest a lack of certain nutritional substances, such as magnesium, can trigger eyelid spasms. These reports are not conclusive but eat a balanced diet full of green leafy veggies to be sure you are getting all your essential minerals and vitamins. If not, take a multivitamin daily.

Allergies. People with eye allergies can have itching, swelling and watery eyes. When eyes are rubbed, this releases histamine into the lid tissues and the tears. This is significant, because some evidence indicates that histamine can cause eyelid twitching.

To offset this problem, some eye doctors have recommended antihistamine eye drops or tablets to help some eyelid twitches. But remember that antihistamines also can cause dry eyes. It’s best to work with your eye doctor to make sure you’re doing the right thing for your eyes.

Summary:

-

An eyelid twitch is a repetitive, involuntary spasm of the eyelid muscle.

-

Chronic and uncontrollable eyelid twitches are a sign of benign essential blepharospasm.

-

Very rarely, eyelid spasms are a symptom of a more serious brain or nerve disorder.

If the spasms become chronic, you may have what’s known as “benign essential blepharospasm,” which is the name for chronic and uncontrollable eyelid movement. This condition typically affects both eyes. The exact cause of the condition is unknown, but the following may make spasms worse:

-

blepharitis, or inflammation of the eyelid

-

conjunctivitis, or pinkeye

-

dry eyes

-

environmental irritants, such as the wind, bright lights, the sun, or air pollution

-

fatigue

-

light sensitivity

-

stress

-

too much alcohol or caffeine

-

smoking

Benign essential blepharospasm is more common in women than in men. According to Genetics Home Reference, it affects approximately 50,000 Americans and usually develops in middle to late adulthood. The condition will likely worsen over time, and it may eventually cause blurry vision, increased sensitivity to light, and facial spasms.

Very rarely, eyelid spasms are a symptom of a more serious brain or nerve disorder. When the eyelid twitches are a result of these more serious conditions, they are almost always accompanied by other symptoms. Brain and nerve disorders that may cause eyelid twitches include:

-

Bell’s palsy (facial palsy), which is a condition that causes one side of your face to droop downward

-

Dystonia, which causes unexpected muscle spasms and the affected area’s body part to twist or contort

-

Cervical dystonia (spasmodic torticollis), which causes the neck to randomly spasm and the head to twist into uncomfortable positions

-

Multiple sclerosis (MS), which is a disease of the central nervous system that causes cognitive and movement problems, as well as fatigue

-

Parkinson’s disease, which can cause trembling limbs, muscle stiffness, balance problems, and difficulty speaking

-

Tourette’s syndrome, which is characterized by involuntary movement and verbal tics

Undiagnosed corneal scratches can also cause chronic eyelid twitches but there is usually significant eye pain and redness.

Eyelid twitches are rarely serious enough to require emergency medical treatment. However, chronic eyelid spasms may be a symptom of a more serious brain or nervous system disorder. You may need to see your doctor if you’re having chronic eyelid spasms and any of the following also happens:

-

Your eye is red, swollen, or has an unusual discharge.

-

Your upper eyelid is drooping.

-

Your eyelid completely closes each time your eyelids twitch.

-

The twitching continues for several weeks.

-

The twitching begins affecting other parts of your face.

Most eyelid spasms go away without treatment in a few days or weeks. If they don’t go away, you can try to eliminate or decrease potential causes. The most common causes of eyelid twitch are stress, fatigue, and caffeine. To ease eye twitching, you might want to try the following:

-

Drink less caffeine.

-

Get adequate sleep.

-

Keep your eye surfaces and membranes lubricated with over-the-counter artificial tears or eye drops.

-

Apply a warm compress to your eyes when a spasm begins.

Botulinum toxin (Botox) injections are sometimes used to treat benign essential blepharospasm. Botox may ease severe spasms for a few months. However, as the effects of the injection wear off, you may need further injections.

Here is a thorough review of how Botox is given. It is minimally painful in most patients and short procedure with few complications. The most common complication is permanent lid droop that does resolve with time in which case a lid lift is needed. This is uncommon, but this happened to a friend who had Botox for wrinkles by an eyeMD in Miami. She eventually needed eyelift surgery.

Here is a thorough review of how Botox is given. It is minimally painful in most patients and short procedure with few complications. The most common complication is permanent lid droop that does resolve with time in which case a lid lift is needed. This is uncommon, but this happened to a friend who had Botox for wrinkles by an eyeMD in Miami. She eventually needed eyelift surgery.

Surgery to remove some of the muscles and nerves in the eyelids (myectomy) can also treat more severe cases of benign essential blepharospasm. Physical therapy may also be useful for training the muscles in your face to relax.

Lifestyle treatments may also help ease the symptoms of benign essential blepharospasm. Coenzyme Q10 is one treatment, but you should ask your doctor about it first if you have Parkinson’s disease. Treatments also include:

-

acupuncture

-

biofeedback

-

hypnosis

-

massage therapy

-

nutrition therapy

-

psychotherapy, which can be helpful for Tourette’s syndrome

-

tai chi

-

yoga and other meditation techniques for relaxation

If your eyelid spasms are happening more frequently over time, keep a journal and note when they occur. Note your intake of caffeine, tobacco, and alcohol, as well as your level of stress and how much sleep you’ve been getting in the periods leading up to and during the eyelid twitching.

If you notice that you get more spasms when you aren’t getting enough sleep, try to go to bed 30 minutes to an hour earlier to help ease the strain on your eyelids and to reduce your spasms.

Hemifacial spasm – Unilateral facial contraction due to seventh nerve dysfunction

Essential blepharospasm

Meige syndrome – Blepharospasm and oral facial dystonia

Spastic-paretic facial contracture – Unilateral tonic facial contracture due to pontine dysfunction, associated usually with multiple sclerosis, and brainstem tumors or vascular lesions

-

Benign Essential Blepharospasm

-

Hemifacial Spasm

-

Myokymia

A complete cranial nerve examination should be performed.

If the myokymia is not seen in the office, patients should be encouraged to video-document their episodes.

Brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is not needed for typical eyelid myokymia but should be considered if facial myokymia, hemifacial spasm, or spastic paretic facial contracture is suspected, as well as when eyelid myokymia is continuous.

What cases Fainting or a Sudden Loss of Consciousness?

Fainting (syncope) is a sudden loss of consciousness from a lack of blood flow to the brain. People who faint usually wake up quickly after collapsing. Management for this condition is simple, usually requiring little more than letting the victim recover while lying flat (supine). More important than immediate management is treating the cause of the fainting. Often, the only way to identify the cause is to look at the victim’s chronic medical problems, if any, and recent activities or illnesses.

Most fainting is triggered by the vagus nerve. It connects the digestive system to the brain, and its job is to manage blood flow to the gut. When food enters the system, the vagus nerve directs blood to the stomach and intestines, pulling it from other body tissues, including the brain. Unfortunately, the vagus nerve can get a little too excited and pull too much blood from the brain. Some things make it work harder, such as bearing down to have a bowel movement or vomiting. Conditions that drop blood pressure amplify the effects of the vagus nerve.

Folks who are prone to this condition (syncope) commonly begin fainting at around 13 years old and continue for the rest of their lives. Fainting usually follows a pattern. The victim will feel flush (warm or hot are also common feelings) followed by sudden weakness and loss of consciousness. They’ll go limp and often break out in a cold sweat.

People who are standing when they faint, or “pass out,” will collapse to the ground. In some folks with a hyper vagus nerve, stimulating it causes the heart to slow drastically. However, once the victim actually passes out, the vagus nerve stops doing its thing, and the victim’s heart begins to speed up in order to fix the low blood pressure.

Too little water in the bloodstream lowers blood pressure, and stimulating the vagus nerve when the system is already a quart low leads to dizziness and fainting. There are many causes of dehydration: vomiting or diarrhea, heat exhaustion, burns and more. Vomiting and diarrhea, specifically, also stimulate the vagus nerve — talk about a double whammy.

Do you pass out when you see blood? Anxiety, panic disorder, and stress can stimulate the vagus nerve in some people and lead to a loss of consciousness.

Not all losses of consciousness are related to the vagus nerve. Shock is a condition characterized by low blood pressure that often leads to a loss of consciousness. As a society, we are very aware of the long-term consequences of high blood pressure, but very low blood pressure is much more immediately dangerous.

Shock is a life-threatening emergency that usually comes from bleeding, but can also come from severe allergy (anaphylaxis) or severe infection.

People with shock will most likely become confused, then lose consciousness as their condition gets worse. It can all happen very quickly, and although it’s not fainting per se, we can’t really tell unless the victim wakes up. Taking a wait and see attitude may be dangerous.

Plenty of people lose consciousness due to alcohol use, and we don’t call it fainting (although passing out still seems appropriate). Besides its obvious sedation effect, alcohol makes you urinate, which will eventually lead to dehydration. It also dilates blood vessels, which decreases blood pressure. Combining those effects drains the brain and turns out the lights.

Like shock, losing consciousness due to alcohol is not technically considered fainting, but it may or may not be cause for concern. It is possible to die fromalcohol poisoning, and passing out is a sign of serious intoxication. Other drugs — legal as well as illegal — can knock you out for a variety of reasons, and some are serious causes of dehydration or drops in blood pressure.

Your heart is the pump that forces blood through your veins and arteries. It takes a certain amount of pressure in the bloodstream to keep it flowing. A correctly functioning heart is essential to maintaining adequate blood pressure. If the heart beats too fast or too slow, it can’t keep the blood pressure up as high as it needs to be. Blood drains from the brain and leads to fainting. During a heart attack, the heart muscle can become too weak to maintain blood pressure.

To decide if the heart may be the culprit, take a pulse. If it’s too fast (more than 150 beats per minute) or too slow (less than 50 beats per minute), suspect that the heart caused the fainting spell. Also, if the victim is complaining of chest pain or othersymptoms of a heart attack, assume the heart is too weak to keep blood in the head.

All by itself, fainting is not life-threatening. However, sudden cardiac arrest looks a lot like fainting and requires immediate treatment. Whenever you see someone pass out, make sure the patient is breathing; if not, call 911 and begin CPR.

Once someone faints, get the patient comfortably lying flat. You can elevate the legs to help blood flow return to the brain, but it is generally not necessary and there’s some debate on whether it is effective.

Treatment after that depends on the cause of fainting. If this is the first time this person has ever fainted — or if you don’t know — call 911. There are some dangerous conditions that can cause fainting and should be evaluated by medical professionals to determine how to proceed.

If the patient has a history of fainting, watch the breathing and give him a couple of minutes to wake up. If the patient doesn’t wake up within three minutes of lying flat, call 911.

More important than immediate treatment is to treat the cause of the fainting. Often, the only way to identify the cause is to look at the patient ‘s chronic medical problems, if any, and recent activities or illnesses.

Sometimes, there’s absolutely nothing you can do to stop from fainting, but if you feel it coming on there are a few things that may help. If you feel suddenly flushed, hot, nauseated or break out in a cold sweat, don’t stand up. Lie down until it passes. If it doesn’t pass in a few minutes or you begin to experience chest pain or shortness of breath, call 911.

Knowledge is half the battle. Patients of multiple fainting spells should definitely see a doctor and determine the cause of the fainting (if any). Patients will often learn the warning signs and symptoms of fainting and can learn to avoid it.

——————–

If nothing is helping and symptoms still continue, we think of Dystonia:

Trauma-induced Dystonia

What is Dystonia?

Dystonia is a movement disorder.

Dystonia is characterized by persistent or intermittent muscle contractions causing abnormal, often repetitive, movements, postures, or both. The movements are usually patterned and twisting, and may resemble a tremor. Dystonia is often initiated or worsened by voluntary movements, and symptoms may “overflow” into adjacent muscles. Dystonia is classified by: 1. clinical characteristics (including age of onset, body distribution, nature of the symptoms, and associated features such as additional movement disorders or neurological symptoms) and 2. Cause (which includes changes or damage to the nervous system and inheritance). Doctors use these classifications to guide diagnosis and treatment.

There are multiple forms of dystonia, and dozens of diseases and conditions may include dystonia as a symptom. Dystonia may affect a single body area or be generalized throughout multiple muscle groups. Dystonia affects men, women, and children of all ages and backgrounds. Estimates suggest that no fewer than 300,000 people are affected in the United States and Canada alone. Dystonia causes varying degrees of disability and pain, from mild to severe. There is not yet a cure, but multiple treatment options exist and scientists around the world are actively pursuing research toward new therapies.

There are multiple forms of dystonia, and dozens of diseases and conditions may include dystonia as a symptom. Dystonia may affect a single body area or be generalized throughout multiple muscle groups. Dystonia affects men, women, and children of all ages and backgrounds. Estimates suggest that no fewer than 300,000 people are affected in the United States and Canada alone. Dystonia causes varying degrees of disability and pain, from mild to severe. There is not yet a cure, but multiple treatment options exist and scientists around the world are actively pursuing research toward new therapies.

Although there are several forms of dystonia and the symptoms may outwardly appear quite different, the element that all forms share is the repetitive, patterned, and often twisting involuntary muscle contractions. Dystonia is a chronic disorder, but the vast majority of dystonias do not impact cognition, intelligence, or shorten a person’s life span.

Dystonia symptoms may follow trauma to the head, and/or trauma to a specific body area.

Dystonia symptoms following head trauma often affect the side of the body which is opposite to the side of the brain injured by the trauma. Examples of peripheral injury include oromandibular dystonia following dental procedures, blepharospasm following surgery or injury to the eyes, and cervical dystonia following whiplash or other neck injury. Symptoms of trauma-induced dystonia may be paroxysmal (meaning that they occur in episodes or attacks of symptoms), not respond to sensory tricks, and persist during sleep.

Brain trauma will often manifest in observable lesions in the brain that can be assessed by neuroimaging techniques. Onset of symptoms may be delayed by several months or years after trauma. Clues to whether dystonia to a specific body part can be attributed peripheral injury to that body area include:

Dystonia symptoms following head trauma often affect the side of the body which is opposite to the side of the brain injured by the trauma. Examples of peripheral injury include oromandibular dystonia following dental procedures, blepharospasm following surgery or injury to the eyes, and cervical dystonia following whiplash or other neck injury. Symptoms of trauma-induced dystonia may be paroxysmal (meaning that they occur in episodes or attacks of symptoms), not respond to sensory tricks, and persist during sleep.

Brain trauma will often manifest in observable lesions in the brain that can be assessed by neuroimaging techniques. Onset of symptoms may be delayed by several months or years after trauma. Clues to whether dystonia to a specific body part can be attributed peripheral injury to that body area include:

- The injury is severe enough to cause local symptoms that persist for at least two weeks or require medical evaluation within two weeks;

- The onset of the movement disorder occurs within a few days or months (up to a year) after the injury;

- The symptoms relate anatomically to the injured part of the body.

In addition to dystonia, movement disorders that are believed to result from brain and peripheral trauma include parkinsonism, tremors, chorea, myolconus, tics, and hemifacial or hemimasticatory spasm.

Terms used to describe trauma-induced dystonia include: injury-induced, peripherally-induced (when trauma is to affected body area, not brain), post-traumatic dystonia, causalgia-dystonia syndrome, reflex sympathetic dystrophy with dystonia

Diagnosis

Many of the ascribed causes of secondary dystonia are based on historical information or subtle characteristics of the symptoms, and have no diagnostic, radiologic, serologic, or other pathologic trademark.

Treatment

Oral medications are often the mainstay of treatment for secondary dystonia. Although there is no single drug that helps an overwhelming number of individuals, there are several that may be of benefit. These oral medications include levodopa, trihexyphenidyl, clonazepam, and baclofen (oral and intrathecal especially for dystonia and spasticity). Medications may be taken in combination.

Botulinum toxin injections may be used to treat specific body parts that may be affected, such as the neck, jaw, hands, or feet.

Several surgical techniques may be appropriate for select individuals who do not respond to medications and botulinum toxin injections. These include ablative surgeries such as pallidotomy and thalamotomy, intrathecal baclofen, and deep brain stimulation.

Terms used to describe trauma-induced dystonia include: injury-induced, peripherally-induced (when trauma is to affected body area, not brain), post-traumatic dystonia, causalgia-dystonia syndrome, reflex sympathetic dystrophy with dystonia

Diagnosis

Many of the ascribed causes of secondary dystonia are based on historical information or subtle characteristics of the symptoms, and have no diagnostic, radiologic, serologic, or other pathologic trademark.

Treatment

Oral medications are often the mainstay of treatment for secondary dystonia. Although there is no single drug that helps an overwhelming number of individuals, there are several that may be of benefit. These oral medications include levodopa, trihexyphenidyl, clonazepam, and baclofen (oral and intrathecal especially for dystonia and spasticity). Medications may be taken in combination.

Botulinum toxin injections may be used to treat specific body parts that may be affected, such as the neck, jaw, hands, or feet.

Several surgical techniques may be appropriate for select individuals who do not respond to medications and botulinum toxin injections. These include ablative surgeries such as pallidotomy and thalamotomy, intrathecal baclofen, and deep brain stimulation.

References:

https://www.dystonia-foundation.org/what-is-dystonia

http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1212176-overview