I love the article below (** use find to find it below this main post) from 2014 from Scientific America Mind about Acupuncture. It is hysterical. I would most like to meet Dr. Hall and pharmacist David Colquhoun, who appears to be a true Brit & very cynical. The consensus back then was that there was little to no scientific proof acupuncture works.

In 2020, I still see many patients who “swear” acupuncture works for various pains. I did post in 2017 about why acupuncture likely works given the stimulation of the fascial plain surrounding muscles and the piezoelectricity inherent to the fascial plane.

https://drcremers.com/2017/04/myofascial-pain-syndrome-and-science.html

As discussed in that old post, part of the issue in proving acupuncture works involves the subjective nature of quantifying “pain” and all that means.

Recently a patient who was having life-debilitating severe dry eye pain (10 out of 10) began a series of treatments with Intense Pulse Light. He improved significantly as the meibomian gland oil was expressed over many sessions and went from “toothpaste secretions” to “olive oil.” But he seemed to hit a wall where he could not get more pain relief (the best was 5 out of 10 eye pain). He saw a very good acupuncturist who appears to have helped with the pain even more.

There is no way to tell if his relief was from the IPL’s long term effect or if it is from acupuncture, but he is significantly better with IPL plus acupuncture. Of course, this is only 1 story (1 case), but it is interesting to me as a surgeon as we do have some patients who do not get to a “no-pain” state, and we do want our patients to have ZERO pain.

It will take years and millions of dollars to prove definitely acupuncture works for general conditions and even more time and money to prove it helps with dry eye. Still, it is interesting to think of the causes of chronic eye pain and to treat the whole person and all the factors involved.

There are many articles looking to prove the effectiveness of acupuncture as it does appear to help many patients.

This is the name of the acupuncturist my patient really loved:

Hoffecker , using herbs and accupuncture for relief of allergies. Patient has

been feeling improvement with itching

Changes in resting‐state functional connectivity in nonacute sciatica with acupuncture modulation: A preliminary study

Abstract

Aims

Methods

Results

Conclusions

1 INTRODUCTION

2 METHODS

2.1 Participants

| Characteristics | Before acupuncture (n = 12) | After acupuncture (n = 12) | p‐Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (M/F) | 6/6 | 6/6 | — |

| Age (years) | 61.42 ± 14.84 | — | — |

| Duration (months) | 20.75 ± 16.44 | — | — |

| Side (right/left) | 6/6 | — | |

| VAS | 5.42 ± 1.83 | 3.92 ± 1.83 | .032* |

| SBI | 11.83 ± 5.37 | 9.42 ± 4.10 | .287 |

| RDQS | 10.75 ± 4.85 | 7.17 ± 5.04 | .036* |

| WHOQOL‐BREF, total | 53.19 ± 9.48 | 52.68 ± 8.28 | .827 |

| Physical | 12.68 ± 2.54 | 13.34 ± 1.87 | .388 |

| Psychological | 13.17 ± 2.55 | 12.91 ± 2.07 | .651 |

| Social | 13.58 ± 3.09 | 12.83 ± 3.46 | .298 |

| Environmental | 13.67 ± 2.61 | 13.41 ± 1.92 | .660 |

Note

- Data are presented as mean ± SD and were compared using independent t test (continuous variables).

- Abbreviations: RDQS, Roland Disability Questionnaire for Sciatica; SBI, Sciatica Bothersomeness Index; VAS, visual analog scale; WHOQOL‐BREF, the World Health Organization Quality of Life in the Brief Edition.

- * p < .05; **p < .01.

2.2 Study design

2.3 Intervention

2.4 Clinical outcome measures

2.5 Image acquisition

2.6 Analysis of resting‐state functional MRI data

2.6.1 Image preprocessing

2.6.2 Imaging postprocessing: ReHo analysis

2.6.3 Functional connectivity analysis of ReHo‐based seeds

2.7 Statistical analysis

2.7.1 Demographic and behavior data

2.7.2 Image data: ReHo and ReHo‐seeded FC

2.7.3 Correlation analyses

3 RESULTS

3.1 Baseline information and demographic data

3.2 Measurements of pain and quality of life

3.3 Intra‐ and interregional connectivity of ReHo

| Contrast | Region | BA | Size | t score | Coordinate | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| x | y | z | |||||

| Effect of sciatica (between groups) | |||||||

| HC > Pretreat | NS | ||||||

| Pretreat > HC | PCC | 23 | 450 | 9.94 | −9 | −42 | 30 |

| Effect of treatment | |||||||

| Between groups | |||||||

| Post‐treat > HC | Precentral gyri | 4 | 193 | 7.66 | 24 | −21 | 51 |

| HC > Post‐treat | NS | ||||||

| Within groups | |||||||

| Pretreat > Post‐treat | PCC/PCu | 23 | 381 | 5.21 | 3 | −54 | 21 |

| Post‐treat > Pretreat | NS | ||||||

Note

- Peak coordinates refer to Montreal Neurological Institute space. Significance was set at the uncorrected voxel level p = .005, followed by the family‐wise error‐corrected cluster level p = .05.

- Abbreviations: BA, Brodmann area; HC, healthy control group; NS, nonsignificant; PCC, posterior cingulate cortex; Post‐treat, group with sciatica after an acupuncture treatment; Pretreat, group with sciatica before acupuncture treatment.

3.4 Interregional FC

| Contrast | Region | BA | Size | t score | Coordinate | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| x | y | z | |||||

| Right ReHo seed (3,−54,21) | |||||||

| Effect of sciatica (between groups) | |||||||

| HC > AC pre | NS | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| AC pre > HC | NS | ||||||

| Effect of acupuncture treatment | |||||||

| Between groups | |||||||

| AC post > HC | Insula, right | 13 | 672 | 7.33 | 39 | 12 | 3 |

| Insula, left | 13 | 604 | 6.56 | −51 | 6 | 3 | |

| OFC, right | 10 | 268 | 5.27 | 30 | 51 | 6 | |

| IPL, left | 40 | 301 | 6.34 | −54 | −42 | 39 | |

| IPL, right | 40 | 217 | 6.18 | 48 | −33 | 33 | |

| dACC | 32 | 318 | 5.07 | 12 | 15 | 36 | |

| Cerebellum, fusiform, R | — | 165 | 5.83 | 39 | −57 | −21 | |

| Cerebellum, fusiform, L | — | 486 | 5.07 | −33 | −66 | −18 | |

| AC post < HC | PCu, left | 31 | 1,247 | 10.56 | −3 | −60 | 21 |

| dmPFC, left‐ | 9 | 763 | 5.00 | −15 | 54 | 39 | |

| Cerebellum, tonsil | — | 222 | 5.53 | 6 | −54 | −48 | |

| Within groups | |||||||

| AC pre > AC post | PCC/PCu, left | 23 | 234 | 5.69 | 0 | −30 | 27 |

| AC post > AC pre | NS | — | |||||

Note

- Peak coordinates refer to Montreal Neurological Institute space. The significance threshold was set at the uncorrected voxel level p = .005, followed by the family‐wise error‐corrected cluster level p = .05.

- Abbreviations: AC, group of sciatica with acupuncture; dACC, dorsal anterior circulate cortex; dmPFC, dorsomedial prefrontal cortex; HC, group of healthy controls; IPL, inferior parietal lobule; NS, nonsignificant; OFC, orbitofrontal cortex; PCC, posterior cingulate cortex; PCu, precuneus; post, post‐treatment; pre, pretreatment.

3.5 Correlation analysis between the FC map and behavior measurements

4 DISCUSSION

5 CONCLUSIONS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Dry Needling as a Treatment Modality for Tendinopathy: a Narrative Review.

Abstract

PURPOSE OF REVIEW:

RECENT FINDINGS:

The effectiveness of dry needling for treatment of tendinopathy has been evaluated in 3 systematic reviews, 7 randomized controlled trials, and 6 cohort studies. The following sites were studied: wrist common extensor origin, patellar tendon, rotator cuff, and tendons around the greater trochanter. There is considerable heterogeneity of the needling techniques, and the studies were inconsistent about the therapy used after the procedure. Most systematic reviews and randomized controlled trials support the effectiveness of tendon needling. There was a statistically significant improvement in the patient-reported symptoms in most studies. Some studies reported an objective improvement assessed by ultrasound. Two studies reported complications. Current research provides initial support for the efficacy of dry needling for tendinopathy treatment. It seems that tendon needling is minimally invasive, safe, and inexpensive, carries a low risk, and represents a promising area of future research. In further high-quality studies, tendon dry needling should be used as an active intervention and compared with appropriate sham interventions. Studies that compare the different protocols of tendon dry needling are also needed.

2. There is no way to tell if the authors have a financial interest in below article on Pubmed nor to access the full article at Johns Hopkins’ Medical system without asking the librarian to find it. Likely the authors do have a financial interest but the abstract is intriguing.

Electroacupuncture reduces fibromyalgia pain by downregulating the TRPV1-pERK signalling pathway in the mouse brain.

Author information

- 1

- College of Chinese Medicine, School of Post-Baccalaureate Chinese Medicine, China Medical University, Taichung.

- 2

- College of Chinese Medicine, Graduate Institute of Acupuncture Science, China Medical University, Taichung.

- 3

- College of Chinese Medicine, Graduate Institute of Integrated Medicine, China Medical University, Taichung.

- 4

- Master’s Program for Traditional Chinese Veterinary Medicine, Chi Institute of Traditional Chinese Veterinary Medicine, Reddick, Florida, USA.

- 5

- Research Center for Chinese Medicine & Acupuncture, China Medical University, Taichung.

Abstract

BACKGROUND:

AIMS:

METHODS:

RESULTS:

CONCLUSION:

Our data suggest that EA can reverse the central sensitisation of the TRPV1-ERK signalling pathway in the mouse brain. Thus, our findings provide mechanistic evidence supporting the potential therapeutic efficacy of EA for treating FM pain.

Electrical interferential current stimulation versus electrical acupuncture in management of hemiplegic shoulder pain and disability following ischemic stroke-a randomized clinical trial.

Abstract

BACKGROUND:

METHODS:

RESULTS:

CONCLUSION:

TRIAL REGISTRATION:

Acupuncture Targeting SIRT1 in the Hypothalamic Arcuate Nucleus Can Improve Obesity in High-Fat-Diet-Induced Rats with Insulin Resistance via an Anorectic Effect.

Abstract

OBJECTIVE:

METHODS:

RESULTS:

CONCLUSION:

Acupuncture and moxibustion stimulate fibroblast proliferation and neoangiogenesis during tissue repair of experimental excisional injuries in adult female Wistar rats.

Author information

- 1

- Biomedical Sciences Graduate Program, Hermínio Ometto University Center, Araras, Brazil.

Abstract

OBJECTIVE:

METHODS:

RESULTS:

CONCLUSIONS:

Getting Well Is More Than Gaining Weight – Patients’ Experiences of a Treatment Program for Anorexia Nervosa Including Ear Acupuncture.

Abstract

Effect of an Acupuncture Technique of Penetrating through Zhibian (BL54) to Shuidao (ST28) with Long Needle for Pain Relief in Patients with Primary Dysmenorrhea: A Randomized Controlled Trial.

Author information

- 1

- Shanxi University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Jinzhong, Shanxi, China.

- 2

- The Third Teaching Hospital of Shanxi University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Taiyuan, Shanxi, China.

Abstract

BACKGROUND:

METHODS:

RESULTS:

CONCLUSIONS:

Efficacy of compatible acupoints and single acupoint versus sham acupuncture for functional dyspepsia: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial.

Author information

- 1

- Department of Acupuncture and Moxibustion, Changchun University of Chinese Medicine, Changchun, 130117 China. Department of rehabilitation, Changchun hospital of traditional Chinese medicine, Changchun, 130022, China.

- 2

- Jilin Ginseng Academy, Changchun University of Chinese Medicine, Changchun, 130117, China.

- 3

- Department of Acupuncture and Moxibustion, Changchun University of Chinese Medicine, Changchun, 130117, China.

- 4

- Department of Disease Prevention, First Affiliated Hospital to Changchun University of Chinese Medicine, Changchun, 130021, China.

- 5

- Department of Endocrinology, First Affiliated Hospital to Changchun University of Chinese Medicine, Changchun, 130021, China.

- 6

- Department of Epidemiology and Health Statistics, School of Public Health, Jinlin University, Changchun, 130021, China.

- 7

- DDepartment of pharmacy, Changchun University of Chinese Medicine, Changchun, 130021, China.

- 8

- Department of Acupuncture and Moxibustion, Changchun University of Chinese Medicine, Changchun, 130117, China. litie1999@126.com.

Abstract

BACKGROUND:

METHODS:

DISCUSSION:

Sometimes myofascial pain syndrome will come and go and cause unusual “other” symptoms, such as periodic dropping of the eyelid, headaches, and migraines.

7. A recent patient told me about a specialist in this area below: Dr. Michael T. Singer

Does Acupuncture and Massaging Work?

Calcite microcrystals in the pineal gland of the human brain: first physical and chemical studies.

Abstract

Fascia Research from a Clinician/Scientist’s Perspective

INTRODUCTION

DISCUSSION

It’s All Connected

And Therapies Actually Do Something

References:

- General Dentistry Residency

- Prosthodontic Residency

- Maxillofacial Prosthodontics Residency

- Orofacial Pain Residency

http://www.michaelsingerdds.com/about_michael_singer.html

2. This is controversial but very interesting. While I do not believe at all that wearing any crystals help with anything: have never seen any worthwhile study to indicate they help, the pineal gland does have very interesting properties that need to be explored more.

https://physics.knoji.com/the-piezoelectric-effect-and-the-pineal-gland-in-the-human-brain/

The Piezoelectric Effect and the Pineal Gland in the Human Brain

As we explored the Piezoelectric effect through my other article pertaining to Quartz Crystal in which we described the Piezoelectric effect as electricity resulting from pressure, which holds an accumulated electric charge as a solid material, in this article we are going to further explore how this effect pertains to the Pineal Gland inside the human brain.

In this article we will be exploring how the Piezoelectric effect relates to the human brain and electromagnetic energies within and outside the human body that pertain to extra sensory perception and energetic sensitivity, especially during exercises that focus on enhancing the electromagnetic response through meditation, dreams and environmental stimulation. In metaphysical literature, the Pineal Gland has been described as the “seat of the soul”, the “third eye”, and “Brow Chakra (Ajna Chakra). The reference to being the “third eye” is quite ironic considering the anatomy of the Pineal Gland has a lens, cornea and retina as does the actual eye.

Physiologically, the Pineal Gland is a pine cone shaped gland of the endocrine system that is approximately the size of a raisin, and is responsible for producing Melatonin which influences sexual development and regulates the sleep cycles in the human brain and body. More specifically, the Pineal gland is responsible for converting Serotonin into Melatonin and is the only gland in the body that does so. It is the first distinguishable gland present in the brain and is recognizable within three weeks gestation of fetal development.

Image Source

Inside the Pineal Gland are Calcite Micro Crystals consisting of Calcium, Carbon and Oxygen that produce bioluminescense; a “cold” light that produces light without heat, ranging in the blue-green light spectrum. In deep sea marine life that uses bioluminescense in the same way, we can look forward to more emphasis on developing the Pineal Gland for transparency within the cellular tissue of the human body. For example, there have been ongoing studies in labs with animals such as rats in which bioluminescent imaging is able to detect cancer or abnormal cell growth in comparison with thermal imaging that makes the study and conclusions more efficient and precise.

Image Source

The Calcite Micro-crystals are said to have their own Piezoelectric effect that is responsive to electromagnetic energies outside the physical body, and can also produce it’s own electromagnetic energy. A new form of bio-mineralization has been studied in the human Pineal Gland using scanning electron microscopy and energy dispersive spectroscopy.

A study conducted in Israel by the Department of Chemical Engineering through the Ben-Gurion University of the Negev in Sheva, these tiny micro-crystals were noted to have a texture that may be noncentrosymmetric because of the structural organization of the sub-unit, even though the single crystals do have a center of symmetry which gives one reason in which the crystals are considered Piezoelectric, similar to the calcite crystals inside the inner ear. Among many results, it is discovered that the calcite micro-crystals would have piezoelectric properties with excitability in the frequency range of mobile communications which brings into question the entire spectrum of energy waves we encounter every day that could, in the long term, create morphological change on cellular membranes of related cells.

What this means is that any energies that produce an electromagnetic response in relation to the Pineal gland could alter energy patterns within the body and brain from the central nervous system to sexual function, sleep cycles or sleep deprivation and hypersensitivity to electromagnetic stimulation through one’s environment.

Image Source

Discovering the alteration that electromagnetic frequency waves of energy has on the Pineal Gland is not new to science, Metaphysicians or spiritualists.

According to author Preston B. Nichols who wrote The Montauk Project copyright © 1992, states that in the 1960’s, military personnel of the Air Force were working on the Sage Radar project on a decommissioned base, Montauk. It was reported that by changing the pulse duration and frequency of the radar that used a middle infrared band of energy waves, they could change the general mood of the people on the base.

Results of stronger pulses of infrared energy waves on the brain, and especially the Calcite Micro-crystals in the Pineal Gland are:

- Sleepiness

- Crying

- Agitation

- Depression

- Anxiety

- Aggression

- Fear

- Terror

- Hopelessness

- Grief

- Apathy

- And even Death

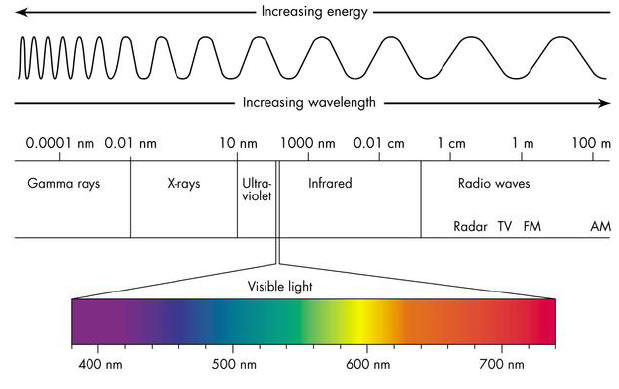

Infrared energy waves are the lower frequency waves on the light spectrum. Low frequency waves have a longer wave length which correspond with lower emotional energies and moods. While higher frequency waves such as those in the green, blue and violet range produce higher emotional energies and moods.

Image Source

The same results can be seen in sound waves as well. A great study for comparison is Dr. Masaru Emoto in his groundbreaking research of how human consciousness can intentionally and unintentionally effect the molecular structure of water, as well as studying the result of sound wave vibrations. For example, research has been done in which large metal plates are subjected to a range of different sound waves that affect grains of sand sitting on top of the metal plate. The conclusion is that the grains of sand develop and shift into geometric patterns and shapes depending on the sound waves that are applied.

Image Source

Metaphysically, quartz crystals resonate very closely with the Piezoelectric effect that the Calcite Micro-crystals produce within the Pineal Gland as well as inner ear, which makes them highly effective for the usage of spiritual endeavors, meditation, altering one’s mood or altering one’s state of well being that range in subtlety or intensity for the individual using crystals as a form of energetic therapy.

Similar to how the lower infrared band of frequency waves can adversely affect the mood and health of the human body, so can the higher frequency waves that can positively affect the mood and health of the human body.

Avoiding geographical areas or electronic equipment that emit large quantities of infrared energy waves supports a more positive experience in relation to the Pineal Gland and assists in keeping in balance the moods, sleep cycles and sexual health of the person.