| Dry eye syndrome |

| dry eye, keratoconjunctivitis sicca, dry eye disease, keratitis sicca |

|

| Classification and external resources |

| Specialty |

ophthalmology |

|

|

|

|

Dry eye syndrome (

DES), also known as

keratoconjunctivitis sicca (KCS), is the condition of having

dry eyes.

[2] Other associated symptoms include irritation, redness, discharge, and easily fatigued eyes. Blurred vision may also occur.

[2] The symptoms can range from mild and occasional to severe and continuous.

[3] Scarring of the

cornea may occur in some cases without treatment.

[2]

Treatment depends on the underlying cause. Artificial tears are the usual first line treatment. Wrap around glasses that fit close to the face may decrease tear evaporation. Stopping or changing certain medications may help. The medication

ciclosporin or

steroid eye drops may be used in some cases. Another opinion is

lacrimal plugs that prevent tears from draining from the surface of the eye. Dry eyes occasionally makes wearing

contact lenses impossible.

[2]

Dry eye syndrome is a common

eye disease.

[3] It affects 5-34% of people to some degree depending on the population looked at.

[5] Among older people it affects up to 70%.

[6] In China it affects about 17% of people.

[7] The phrase “keratoconjunctivitis sicca” means “dryness of the

cornea and

conjunctiva” in Latin.

[8]

Signs and symptoms[edit]

Typical symptoms of dry eye syndrome are dryness, burning

[9] and a sandy-gritty eye irritation that gets worse as the day goes on.

[10] Symptoms may also be described as itchy, scratchy, stingy or tired eyes.

[9][11] Other symptoms are pain, redness, a pulling sensation, and pressure behind the eye.

[9][12] There may be a feeling that something, such as a speck of dirt, is in the eye.

[9][12] The resultant damage to the eye surface increases discomfort and sensitivity to bright light.

[9] Both eyes usually are affected.

[13]

There may also be a stringy discharge from the eyes. Although it may seem strange, dry eye can cause the eyes to water. This can happen because the eyes are irritated. One may experience excessive tearing in the same way as one would if something got into the eye. These reflex tears will not necessarily make the eyes feel better. This is because they are the watery type that are produced in response to injury, irritation, or emotion. They do not have the lubricating qualities necessary to prevent dry eye.

[12]

Because blinking coats the eye with tears, symptoms are worsened by activities in which the rate of blinking is reduced due to prolonged use of the eyes.

[9] These activities include prolonged reading, computer usage, driving, or watching television.

[9][12] Symptoms increase in windy, dusty or smoky (including cigarette smoke) areas, in dry environments high altitudes including airplanes, on days with low humidity, and in areas where an air conditioner (especially in a car), fan, heater, or even a hair dryer is being used.

[10][9][12][13] Symptoms reduce during cool, rainy, or foggy weather and in humid places, such as in the shower.

[9]

Most people who have dry eyes experience mild irritation with no long-term effects. However, if the condition is left untreated or becomes severe, it can produce complications that can cause eye damage, resulting in impaired vision or (rarely) in the loss of vision.

[12]

Symptom assessment is a key component of dry eye diagnosis – to the extent that many believe dry eye syndrome to be a symptom-based disease. Several questionnaires have been developed to determine a score that would allow for dry eye diagnosis. The McMonnies & Ho dry eye questionnaire is often used

[medical citation needed] in clinical studies of dry eyes.

Any abnormality of any one of the three layers of

tears produces an unstable tear film, resulting in symptoms of dry eyes.

[10]

Decreased tear or excessive evaporation[edit]

Keratoconjunctivitis sicca is usually due to inadequate tear production from lacrimal hyposecretion or to excessive tear evaporation.

[10][9] The aqueous tear layer is affected, resulting in aqueous tear deficiency (ATD).

[10] The

lacrimal gland does not produce sufficient tears to keep the entire

conjunctiva and

cornea covered by a complete layer.

[9] This usually occurs in people who are otherwise healthy. Increased age is associated with decreased tearing.

[10] This is the most common type found in postmenopausal women.

[9][14]

Causes include

idiopathic, congenital

alacrima,

xerophthalmia, lacrimal gland

ablation, and sensory denervation.

[10] In rare cases, it may be a symptom of collagen vascular diseases, including

relapsing polychondritis,

rheumatoid arthritis,

granulomatosis with polyangiitis, and

systemic lupus erythematosus.

[10][9][15][16] Sjögren’s syndrome and other

autoimmune diseases are associated with aqueous tear deficiency.

[10][9] Drugs such as

isotretinoin, sedatives, diuretics, tricyclic

antidepressants,

antihypertensives,

oral contraceptives, antihistamines, nasal decongestants, beta-blockers, phenothiazines, atropine, and pain relieving opiates such as morphine can cause or worsen this condition.

[10][9][12][13] Infiltration of the lacrimal glands by

sarcoidosis or tumors, or postradiation fibrosis of the lacrimal glands can also cause this condition.

[10] Recent attention has been paid to the composition of tears in normal or dry eye individuals. Only a small fraction of the estimated 1543 proteins in tears are differentially deficient or upregulated in dry eye, one of which is

lacritin.

[17][18] Topical lacritin promotes tearing in rabbit preclinical studies.

[19] Also, topical treatment of eyes of dry eye mice (Aire knockout mouse model of dry eye) restored tearing, and suppressed both corneal staining and the size of inflammatory foci in lacrimal glands.

[20]

Additional causes[edit]

Aging is one of the most common causes of dry eyes because tear production decreases with age.

[12] Several classes of medications (both prescription and OTC) have been hypothesized as a major cause of dry eye, especially in the elderly. Particularly, anticholinergic medications that also cause dry mouth are believed to promote dry eye.

[21] Dry eye may also be caused by thermal or chemical burns, or (in epidemic cases) by

adenoviruses. A number of studies have found that

diabetics are at increased risk for the disease.

[22][23]

About half of all people who wear contact lenses complain of dry eyes.

[12] There are two potential connections between contact usage and dry eye. Traditionally, it was believed that soft contact lenses, which float on the tear film that covers the cornea, absorb the tears in the eyes.

[12] However, it is also now known that contact usage damages corneal nerve sensitivity, which subsequently may lead to decreased lacrimal gland tear production and dry eye. The effect of contact on corneal nerve sensitivity is well established for hard contacts as well as soft and rigid gas permeable.

[24][25][26] The connection between this loss in nerve sensitivity and tear production is the subject of current research.

[27]

Dry eyes also occurs or gets worse after

LASIK and other

refractive surgeries, in which the corneal nerves are cut during the creation of a corneal

flap.

[12] The corneal nerves stimulate tear secretion.

[12] Dry eyes caused by these procedures usually resolves after several months, but it can be permanent.

[13] Persons who are thinking about refractive surgery should consider this.

[12]

An eye injury or other problem with the eyes or

eyelids, such as bulging eyes or a

drooping eyelid can cause keratoconjunctivitis sicca.

[11] Disorders of the eyelid can impair the complex blinking motion required to spread tears.

[13] Eye injury or disease leading to

Boehm Syndrome may be exacerbated by dry eyes.

Persons with keratoconjunctivitis sicca have elevated levels of tear

nerve growth factor (NGF).

[10] It is possible that this

ocular surface NGF plays an important role in ocular surface inflammation associated with dry eyes.

[10]

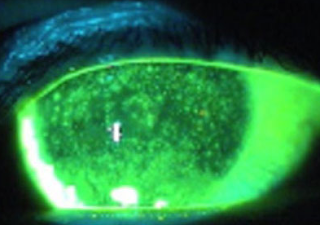

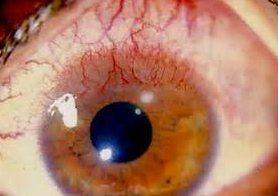

Pathophysiology[edit]

Having dry eyes for a while can lead to tiny

abrasions on the surface of the eyes.

[11] In advanced cases, the

epithelium undergoes pathologic changes, namely

squamous metaplasia and loss of

goblet cells.

[10] Some severe cases result in thickening of the corneal surface, corneal erosion, punctate

keratopathy,

epithelial defects,

corneal ulceration (sterile and infected), corneal

neovascularization, corneal scarring, corneal thinning, and even corneal

perforation.

[10][9]

Another contributing factor maybe

lacritin monomer deficiency. Lacritin monomer, active form of lacritin, is selectively decreased in aqueous deficient dry eye,

Sjogren’s syndrome dry eye, contact lens-related dry eye and in blepharitis.

[18]

Diagnosis[edit]

Dry eyes can usually be diagnosed by the symptoms alone.

[9] Tests can determine both the quantity and the quality of the tears.

[13] A

slit lamp examination can be performed to diagnose dry eyes and to document any damage to the eye.

[10][9]

A

Schirmer’s test can measure the amount of moisture bathing the eye.

[9] This test is useful for determining the severity of the condition.

[12] A five-minute Schirmer’s test with and without anesthesia using a Whatman #41 filter paper 5 mm wide by 35 mm long is performed. For this test, wetting under 5 mm with or without anesthesia is considered diagnostic for dry eyes.

[10]

If the results for the Schirmer’s test are abnormal, a Schirmer II test can be performed to measure reflex secretion.In this test, the nasal mucosa is irritated with a cotton-tipped applicator, after which tear production is measured with a Whatman #41 filter paper. For this test, wetting under 15 mm after five minutes is considered abnormal.

[10]

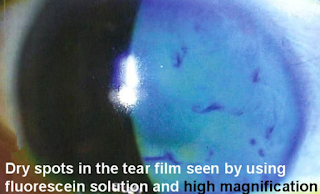

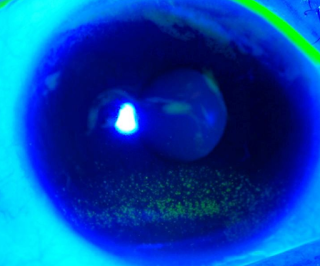

A tear breakup time (TBUT) test measures the time it takes for tears to break up in the eye.

[12] The tear breakup time can be determined after placing a drop of

fluorescein in the cul-de-sac.

[10]

A tear protein analysis test measures the

lysozyme contained within tears. In tears, lysozyme accounts for approximately 20 to 40 percent of total protein content.

[10]

A lactoferrin analysis test provides good correlation with other tests.

[10]

The presence of the recently described molecule Ap4A, naturally occurring in tears, is abnormally high in different states of ocular dryness. This molecule can be quantified biochemically simply by taking a tear sample with a plain Schirmer test. Utilizing this technique it is possible to determine the concentrations of Ap4A in the tears of patients and in such way diagnose objectively if the samples are indicative of dry eye.

[28]

The Tear Osmolarity Test has been proposed as a test for dry eye disease.

[29] Tear osmolarity may be a more sensitive method of diagnosing and grading the severity of dry eye compared to corneal and conjunctival staining, tear break-up time, Schirmer test, and meibomian gland grading.

[30] Others have recently questioned the utility of tear osmolarity in monitoring dry eye treatment.

[18]

Prevention[edit]

There is no way to prevent keratoconjunctivitis sicca. Complications can be prevented by use of wetting and lubricating drops and ointments.

[31]

Treatment[edit]

A variety of approaches can be taken to treatment. These can be summarised as: avoidance of exacerbating factors, tear stimulation and supplementation, increasing tear retention, and eyelid cleansing and treatment of eye inflammation.

[32]

Dry eyes can be exacerbated by smoky environments, dust and air conditioning and by our natural tendency to reduce our blink rate when concentrating. Purposefully blinking, especially during computer use and resting tired eyes are basic steps that can be taken to minimise discomfort.

[32] Rubbing one’s eyes can irritate them further, so should be avoided.

[13] Conditions such as

blepharitis can often co-exist and paying particular attention to cleaning the eyelids morning and night with mild soaps and warm compresses can improve both conditions.

[32]

Environmental control[edit]

Dry, drafty environments and those with smoke and dust should be avoided.

[9] This includes avoiding hair dryers, heaters, air conditioners or fans, especially when these devices are directed toward the eyes. Wearing glasses or directing gaze downward, for example, by lowering computer screens can be helpful to protect the eyes when aggravating environmental factors cannot be avoided.

[13] Using a

humidifier, especially in the winter, can help by adding moisture to the dry indoor air.

[9][11][13][32]

Rehydration[edit]

For mild and moderate cases, supplemental lubrication is the most important part of treatment.

[10]

Application of

artificial tears every few hours

[9] can provide temporary relief. Additional research is necessary to determine whether certain artificial tear formulations are superior to others in treating dry eye.

[33]

Autologous serum eye drops[edit]

None of the commercially available artificial tear preparations include essential tear components such as

epidermal growth factor,

hepatocyte growth factor,

fibronectin,

neurotrophic growth factor, and

vitamin A—all of which have been shown to play important roles in the maintenance of a healthy ocular surface epithelial milieu. Autologous serum eye drops contain these essential factors. However, there is some controversy regarding the efficacy of this treatment. At least one study

[34] has demonstrated that this modality is more effective than artificial tears in a randomized control study. A 2013

Cochrane review found mixed results when comparing autologous serum eye drops to artificial tears or saline.

[35] Evidence from the examined trials showed that autologous serum eye drops resulted in better patient-reported symptoms and improved TBUT, but did not result in improvements in aqueous tear production. No positive effect was observed from ocular surface tests and staining.

Additional options[edit]

Lubricating tear ointments can be used during the day, but they generally are used at bedtime due to poor vision after application.

[10] They contain

white petrolatum,

mineral oil, and similar lubricants.

[10] They serve as a lubricant and an

emollient.

[10] Application requires pulling down the eyelid and applying a small amount (0.25 in) inside.

[10] Depending on the severity of the condition, it may be applied from every hour to just at bedtime.

[10] It should never be used with contact lenses.

[10] Specially designed glasses that form a moisture chamber around the eye may be used to create additional humidity.

[13]

Medication[edit]

Diquafosol, an agonist of the

P2Y2 purinogenic receptor, is approved in Japan for managing dry eye disease by promoting tear secretion.

Lifitegrast is a new drug that was approved by the FDA for the treatment of the condition in 2016.

[38]

Fish and Omega−3 fatty acids consumption[edit]

Consumption of dark fleshed fish containing dietary

omega-3 fatty acids is associated with a decreased incidence of dry eyes syndrome in women.

[39] This finding is consistent with postulated biological mechanisms.

[39] Early experimental work on omega-3 has shown promising results when used in a topical application

[40] or given orally.

[41] A randomized, double-masked study published in 2013 to evaluate the effects of a triglyceride of DHA (Omega-3; Brudy Sec 1.5), showed significant results compared to other methods that are being used.

[42]

Cyclosporin[edit]

Topical

cyclosporin (topical cyclosporin A, tCSA) 0.05% ophthalmic emulsion is an

immunosuppressant.

[10] The drug decreases surface inflammation.

[13] In a trial involving 1200 people, Restasis increased tear production in 15% of people, compared to 5% with placebo.

[12]

It should not be used while wearing contact lenses,

[10] during eye infections

[12] or in people with a history of herpes virus infections.

[13] Side effects include burning sensation (common),

[12] redness, discharge, watery eyes, eye pain, foreign body sensation, itching, stinging, and blurred vision.

[10][12] Long term use of cyclosporin at high doses is associated with an increased risk of cancer.

[43][44]

Cheaper

generic alternatives are available in some countries.

[45]

Conserving tears[edit]

There are methods that allow both natural and artificial tears to stay longer.

[13]

In each eye, there are two

puncta[46] — little openings that drain tears into the tear ducts.

[12] There are methods to partially or completely close the tear ducts.

[13] This blocks the flow of tears into the nose, and thus more tears are available to the eyes.

[9] Drainage into either one or both puncta in each eye can be blocked.

Punctal plugs are inserted into the puncta to block tear drainage.

[12] For people who have not found dry eye relief with drugs, punctal plugs may help.

[12] They are reserved for people with moderate or severe dry eye when other medical treatment has not been adequate.

[12]

If punctal plugs are effective, thermal

[13] or electric

[10] cauterization of puncti can be performed. In thermal cauterization, a local anesthetic is used, and then a hot wire is applied.

[13] This shrinks the drainage area tissues and causes scarring, which closes the tear duct.

[13]

Heating systems that try to unblock the oil glands in the eye has some preliminary evidence of benefit.

[47]

Surgery[edit]

In severe cases of dry eyes,

tarsorrhaphy may be performed where the eyelids are partially sewn together. This reduces the

palpebral fissure (eyelid separation), ideally leading to a reduction in tear evaporation.

[9]

Prognosis[edit]

Keratoconjunctivitis sicca usually is a chronic problem.

[13] Its

prognosis shows considerable variance, depending upon the severity of the condition. Most people have mild-to-moderate cases, and can be treated symptomatically with lubricants. This provides an adequate relief of symptoms.

[10]

When dry eyes symptoms are severe, they can interfere with quality of life.

[12] People sometimes feel their vision blurs with use, or severe irritation to the point that they have trouble keeping their eyes open or they may not be able to work or drive.

[9][12]

Epidemiology[edit]

Keratoconjunctivitis sicca is relatively common within the United States, especially so in older patients.

[10] Specifically, the persons most likely to be affected by dry eyes are those aged 40 or older.

[13] Keratoconjunctivitis sicca is estimated to affect 10% to 20% of adults, with 1 to 4 million aged 65 to 84 affected in the United States.

[48]

While persons with autoimmune diseases have a high likelihood of having dry eyes, most persons with dry eyes do not have an autoimmune disease.

[13] Instances of Sjögren syndrome and keratoconjunctivitis sicca associated with it are present much more commonly in women, with a ratio of 9:1. In addition, milder forms of keratoconjunctivitis sicca also are more common in women.

[10] This is partly because hormonal changes, such as those that occur in pregnancy, menstruation, and menopause, can decrease tear production.

[12][13]

In areas of the world where malnutrition is common, vitamin A deficiency is a common cause. This is rare in the United States.

[31]

Racial predilections do not exist for this disease.

[10]

Synonyms[edit]

Other names for dry eye include dry eye syndrome, keratoconjunctivitis sicca (KCS), dysfunctional tear syndrome, lacrimal keratoconjunctivitis, evaporative tear deficiency, aqueous tear deficiency, and LASIK-induced neurotrophic epitheliopathy (LNE).

[2]

Other animals[edit]

Among other animals, keratoconjunctivitis sicca occurs in dogs, cats, and horses.

[49]

Commonly affected breeds include:

Keratoconjunctivitis sicca is uncommon in

cats. Most cases seem to be caused by chronic conjunctivitis, especially secondary to

feline herpesvirus.

[50] Diagnosis, symptoms, and treatment are similar to those for dogs.

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- Jump up^ Critser, Brice. “Lissamine green staining in keratoconjunctivitis sicca”. Eye Rounds. The University of Iowa. Retrieved 29 July 2016.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f g h “Facts About Dry Eye”. NEI. February 2013. Retrieved 29 July 2016.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Kanellopoulos, AJ; Asimellis, G (2016). “In pursuit of objective dry eye screening clinical techniques.”. Eye and vision (London, England). 3: 1. doi:10.1186/s40662-015-0032-4. PMC 4716631

. PMID 26783543.

. PMID 26783543.

- Jump up^ Tavares Fde, P; Fernandes, RS; Bernardes, TF; Bonfioli, AA; Soares, EJ (May 2010). “Dry eye disease.”. Seminars in ophthalmology. 25 (3): 84–93. doi:10.3109/08820538.2010.488568. PMID 20590418.

- Jump up^ Messmer, EM (30 January 2015). “The pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment of dry eye disease.”. Deutsches Arzteblatt international. 112 (5): 71–81; quiz 82. doi:10.3238/arztebl.2015.0071. PMC 4335585

. PMID 25686388.

. PMID 25686388.

- Jump up^ Ding, J; Sullivan, DA (July 2012). “Aging and dry eye disease.”. Experimental Gerontology. 47 (7): 483–90. doi:10.1016/j.exger.2012.03.020. PMC 3368077

. PMID 22569356.

. PMID 22569356.

- Jump up^ Liu, NN; Liu, L; Li, J; Sun, YZ (2014). “Prevalence of and risk factors for dry eye symptom in mainland china: a systematic review and meta-analysis.”. Journal of ophthalmology. 2014: 748654. doi:10.1155/2014/748654. PMC 4216702

. PMID 25386359.

. PMID 25386359.

- Jump up^ Firestein, Gary S. (2013). Kelley’s textbook of rheumatology (9th ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier/Saunders. p. 1179. ISBN 9781437717389.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y “Keratoconjunctivitis Sicca”. The Merck Manual, Home Edition. Merck & Co., Inc. 2003-02-01. Retrieved 2006-11-12.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al“Keratoconjunctivitis, Sicca”. eMedicine. WebMD, Inc. January 27, 2010. Retrieved September 3, 2010.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d “Dry eyes”. MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia. U.S. National Library of Medicine. 2006-10-04. Retrieved 2006-11-16.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z Michelle Meadows (May–June 2005). “Dealing with Dry Eye”. FDA Consumer Magazine. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Archived from the original on February 23, 2008.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u “Dry eyes”. Mayo Clinic. Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research. 2006-06-14. Retrieved 2006-11-17.

- Jump up^ Sendecka M, Baryluk A, Polz-Dacewicz M (2004). “Częstość występowania zespołu suchego oka” [Prevalence and risk factors of dry eye syndrome]. Przegla̧d Epidemiologiczny (in Polish). 58 (1): 227–33. PMID 15218664.

- Jump up^ Puéchal, X; Terrier, B; Mouthon, L; Costedoat-Chalumeau, N; Guillevin, L; Le Jeunne, C (March 2014). “Relapsing polychondritis.”. Joint, bone, spine : revue du rhumatisme. 81 (2): 118–24. doi:10.1016/j.jbspin.2014.01.001. PMID 24556284.

- Jump up^ Cantarini, L; Vitale, A; Brizi, MG; Caso, F; Frediani, B; Punzi, L; Galeazzi, M; Rigante, D (February–March 2014). “Diagnosis and classification of relapsing polychondritis.”. Journal of autoimmunity. 48-49: 53–9. doi:10.1016/j.jaut.2014.01.026. PMID 24461536.

- Jump up^ Zhou L, Zhao SZ, Koh SK, et al. (July 2012). “In-depth analysis of the human tear proteome”. Journal of Proteomics. 75 (13): 3877–85. doi:10.1016/j.jprot.2012.04.053. PMID 22634083.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Karnati R, Laurie DE, Laurie GW (December 2013). “Lacritin and the tear proteome as natural replacement therapy for dry eye”. Experimental Eye Research. 117: 39–52. doi:10.1016/j.exer.2013.05.020. PMC 3844047

. PMID 23769845.

. PMID 23769845.

- Jump up^ Samudre S, Lattanzio FA, Lossen V, et al. (August 2011). “Lacritin, a novel human tear glycoprotein, promotes sustained basal tearing and is well tolerated”. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 52 (9): 6265–70. doi:10.1167/iovs.10-6220. PMC 3176019

. PMID 21087963.

. PMID 21087963.

- Jump up^ Vijmasi T, Chen FY, Balasubbu S, Gallup M, McKown RL, Laurie GW, McNamara NA (July 2014). “Topical administration of lacritin is a novel therapy for aqueous-deficient dry eye disease.”. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 55 (8): 5401–9. doi:10.1167/iovs.14-13924. PMC 4148924

. PMID 25034600.

. PMID 25034600.

- Jump up^ Fraunfelder FT, Sciubba JJ, Mathers WD (2012). “The role of medications in causing dry eye”. Journal of Ophthalmology. 2012: 285851. doi:10.1155/2012/285851. PMC 3459228

. PMID 23050121.

. PMID 23050121.

- Jump up^ Kaiserman I, Kaiserman N, Nakar S, Vinker S (March 2005). “Dry eye in diabetic patients”. American Journal of Ophthalmology. 139 (3): 498–503. doi:10.1016/j.ajo.2004.10.022. PMID 15767060.

- Jump up^ Li H, Pang G, Xu Z (2004). “Tear film function of patients with type 2 diabetes”. Zhongguo Yi Xue Ke Xue Yuan Xue Bao. 26 (6): 682–6. PMID 15663232.

- Jump up^ Millodot M (1978). “Effect of long term wear of hard contact lenses on corneal sensitivity”. Arch Ophthalmol. 96 (7): 1225–7. doi:10.1001/archopht.1978.03910060059011. PMID 666631.

- Jump up^ Macsai MS, Varley GA, Krachmer JH (1990). “Development of keratoconus after contact lens wear. Patient characteristics”. Arch Ophthalmol. 108 (4): 534–8. doi:10.1001/archopht.1990.01070060082054. PMID 2322155.

- Jump up^ Murphy PJ, Patel S, Marshall J (2001). “The effect of long term daily contact lens wear on corneal sensitivity”. Cornea. 20 (3): 264–9. doi:10.1097/00003226-200104000-00006. PMID 11322414.

- Jump up^ Mathers WD, Scerra C (2000). “Dry eye; investigators look at syndrome with new model”. Ophthalmol Times. 25 (7): 1–3.

- Jump up^ Peral A, Carracedo G, Acosta MC, Gallar J, Pintor J (September 2006). “Increased levels of diadenosine polyphosphates in dry eye”. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 47 (9): 4053–8. doi:10.1167/iovs.05-0980. PMID 16936123.

- Jump up^ Tomlinson, A (April 2007). “DEWS Report, Ocular Surface April 2007 Vol 5 No 2” (PDF).

- Jump up^ “American Academy of Ophthalmology Cornea/External Disease Panel. 2011 Preferred Practice Pattern® (PPP) guidelines”. October 2011.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “Dry eyes syndrome”. MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia. U.S. National Library of Medicine. 2006-10-04. Retrieved 2006-11-16.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d Lemp MA. (2008). “Management of Dry Eye”. American Journal of Managed Care. 14 (4): S88–S101. PMID 18452372. Retrieved 2008-07-25.

- Jump up^ Pucker AD, Ng SM, Nichols JJ (2016). “Over the counter (OTC) artificial tear drops for dry eye syndrome”. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2: CD009729. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009729.pub2. PMID 26905373.

- Jump up^ Kojima, T.; Higuchi, A.; Goto, E.; Matsumoto, Y.; Dogru, M.; Tsubota, K. (2008). “Autologous Serum Eye Drops for the Treatment of Dry Eye Diseases”. Cornea. 27: S25–S30. doi:10.1097/ICO.0b013e31817f3a0e. PMID 18813071.

- Jump up^ Pan Q, Angelina A, Zambrano A, Marrone M, Stark WJ, Heflin T, Tang L, Akpek EK (2013). “Autologous serum eye drops for dry eye”. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 10: CD009327. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009327.pub2. PMC 4007318

. PMID 23982997.

. PMID 23982997.

- Jump up^ Tatlipinar S, Akpek E (2005). “Topical cyclosporine in the treatment of ocular surface disorders”. Br J Ophthalmol. 89 (10): 1363–7. doi:10.1136/bjo.2005.070888. PMC 1772855

. PMID 16170133.

. PMID 16170133.

- Jump up^ Barber L, Pflugfelder S, Tauber J, Foulks G (2005). “Phase III safety evaluation of cyclosporine 0.1% ophthalmic emulsion administered twice daily to dry eye disease patients for up to 3 years”. Ophthalmology. 112 (10): 1790–4. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2005.05.013. PMID 16102833.

- Jump up^ “FDA approves new medication for dry eye disease”. FDA. July 12, 2016. Retrieved 13 July2016.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Miljanović B, Trivedi KA, Dana MR, Gilbard JP, Buring JE, Schaumberg DA (2005). “Relation between dietary n-3 and n-6 fatty acids and clinically diagnosed dry eye syndrome in women”. Am J Clin Nutr. 82 (4): 887–93. PMC 1360504

. PMID 16210721.

. PMID 16210721.

- Jump up^ Rashid S, Jin Y, Ecoiffier T, Barabino S, Schaumberg M, Dana RD (2008). “Topical Omega-3 and Omega-6 Fatty Acids for Treatment of Dry Eye”. Arch Ophthalmol. 126 (2): 219–225. doi:10.1001/archophthalmol.2007.61. PMID 18268213.

- Jump up^ Creuzot C, Passemard M, Viau S, Joffre C, Pouliquen P, Elena PP, Bron A, Brignole F (2008). “Improvement of dry eye symptoms with polyunsaturated fatty acids”. J Fr Ophthalmol. 29 (8): 868–73. PMID 17075501.

- Jump up^ Oleñik A, Jiménez-Alfaro I, Alejandre-Alba N, Mahillo-Fernández I (2013). “A randomized, double-masked study to evaluate the effect of omega-3 fatty acids supplementation in meibomian gland dysfunction”. Clinical Interventions in Aging. 8: 1133–8. doi:10.2147/CIA.S48955. PMC 3770496

. PMID 24039409.

. PMID 24039409.

- Jump up^ “Restasis” (PDF). Allergan. January 2008. Retrieved 2008-07-23.

- Jump up^ Dantal J, Hourmant M, Cantarovich D, Giral M, Blancho G, Dreno B, Soulillou JP (1998). “Effect of long-term immunosuppression in kidney-graft recipients on cancer incidence: randomised comparison of two cyclosporin regimens”. The Lancet. 351 (9103): 623–628. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(97)08496-1. PMID 9500317.

60 patients developed cancers, 37 in the normal-dose group and 23 in the low-dose group (p<0.034); 66% were skin cancers (26 vs 17; p<0.05). The low-dose regimen was associated with fewer malignant disorders but more frequent rejection.

- Jump up^ “Sun Pharma Product List”. Sun Pharma. Archived from the original on 2007-02-13. Retrieved 2006-11-27.

- Jump up^ Carter SR (June 1998). “Eyelid disorders: diagnosis and management”. American Family Physician. 57 (11): 2695–702. PMID 9636333.

- Jump up^ Qiao, J; Yan, X (2013). “Emerging treatment options for meibomian gland dysfunction.”. Clinical ophthalmology (Auckland, N.Z.). 7: 1797–803. doi:10.2147/OPTH.S33182. PMC 3772773

. PMID 24043929.

. PMID 24043929.

- Jump up^ Ervin AM, Wojciechowski R, Schein O (2010). “Punctal occlusion for dry eye syndrome”. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 9: CD006775. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006775.pub2. PMC 3729223

. PMID 20824852.

. PMID 20824852.

- Jump up^ “Keratoconjunctivitis, Sicca”. The Merck Veterinary Manual. Merck & Co., Inc. Retrieved 2006-11-18.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e Gelatt, Kirk N. (ed.) (1999). Veterinary Ophthalmology (3rd ed.). Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 0-683-30076-8.

Further reading[edit]

- Maskin, Steven L. (2007-05-28). Reversing Dry Eye Syndrome: Practical Ways to Improve Your Comfort, Vision, and Appearance. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-12285-5.

- Latkany, Robert (2007-04-03). The Dry Eye Remedy: The Complete Guide to Restoring the Health and Beauty of Your Eyes. Hatherleigh Press. ISBN 978-1-57826-242-7.

- Patel, Sudi; Blades, Kenny (2003-04-10). The Dry Eye: A Practical Approach. Butterworth-Heinemann. ISBN 978-0-7506-4978-0.

- Geerling, Gerd; Brewitt, Horst (June 2008). Surgery for the Dry Eye: Scientific Evidence and Guidelines for the Clinical Management of Dry Eye Associated Ocular Surface Disease. S. Karger AG. ISBN 978-3-8055-8376-3.

- Asbell, Penny A.; Lemp, Michael A. (November 2006). Dry Eye Disease: The Clinician’s Guide to Diagnosis And Treatment. Thieme Medical Publishers. ISBN 978-1-58890-412-6.

External links[edit]

. PMID 26783543.

. PMID 26783543. . PMID 25686388.

. PMID 25686388. . PMID 22569356.

. PMID 22569356. . PMID 25386359.

. PMID 25386359. . PMID 23769845.

. PMID 23769845. . PMID 21087963.

. PMID 21087963. . PMID 25034600.

. PMID 25034600. . PMID 23050121.

. PMID 23050121. . PMID 23982997.

. PMID 23982997. . PMID 16170133.

. PMID 16170133. . PMID 16210721.

. PMID 16210721. . PMID 24039409.

. PMID 24039409. . PMID 24043929.

. PMID 24043929. . PMID 20824852.

. PMID 20824852.